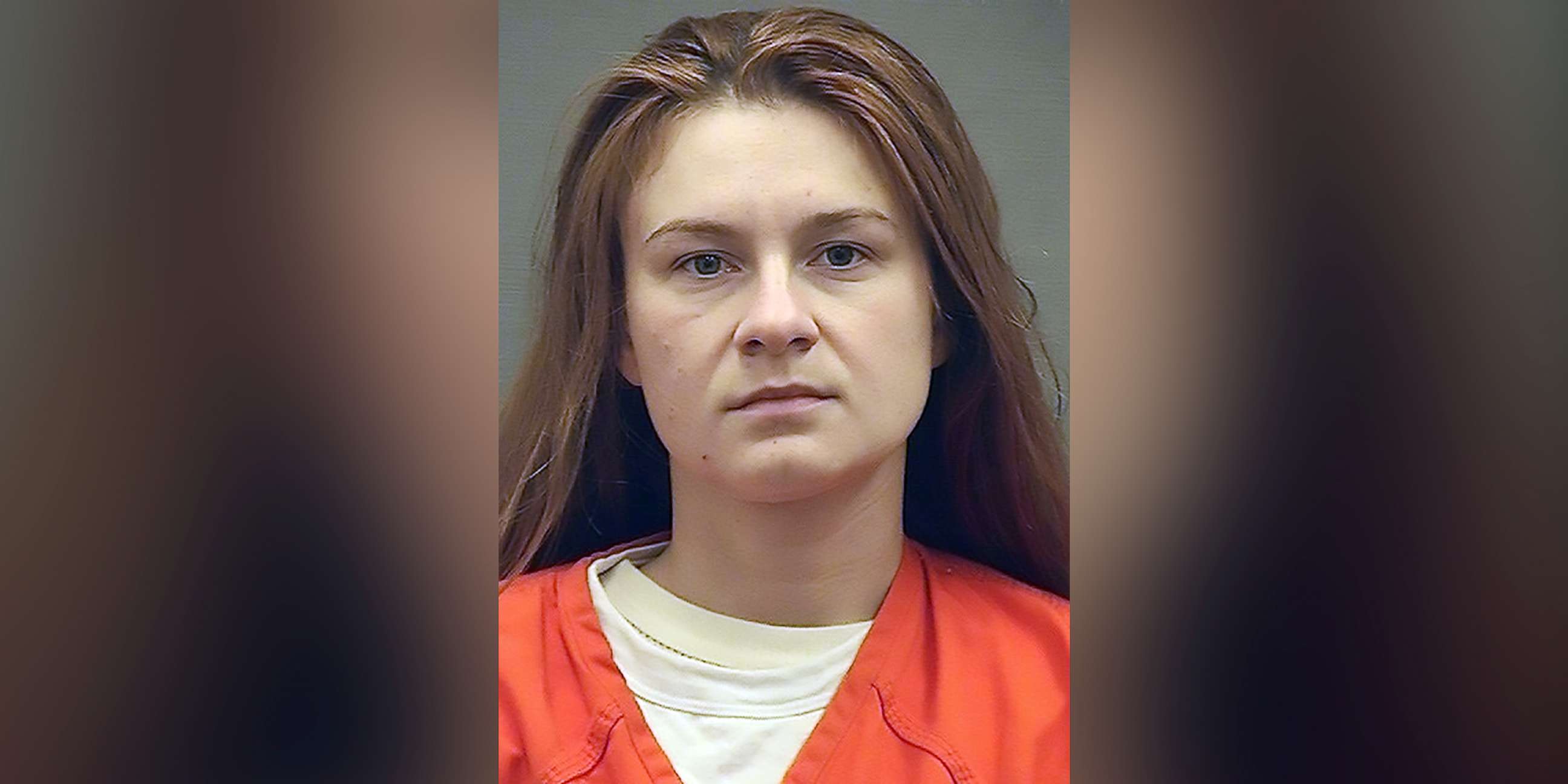

Alleged Russian agent Maria Butina in her own words: 'Truth is my best defender'

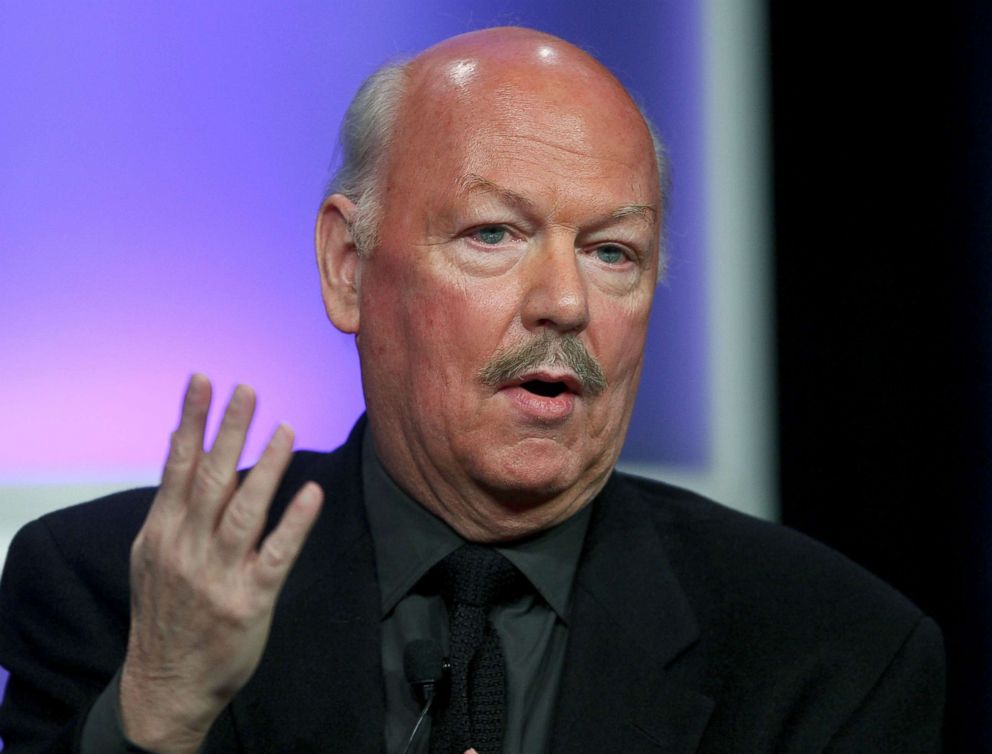

Journalist James Bamford shared recorded conversations with Maria Butina.

For the very first time, alleged Russian agent Maria Butina can be heard telling her side of the story.

In a series of recorded conversations with journalist James Bamford, whose several-thousand-word defense of Butina titled "The Spy Who Wasn't" appears in this month's issue of The New Republic, the 30-year-old Russian gun-rights activist denied the U.S. government's salacious allegations against her.

"Truth is my best defender here," Butina told Bamford, who shared some of his recordings with ABC News. "If I would be the Russian spy, you would never see me in public. I mean, I would be the most unseen person on Earth."

Butina's arrest in July sparked international headlines. Federal prosecutors accused the gun-loving graduate student of being a Kremlin agent, ensnaring Paul Erickson, a 56-year-old conservative political operative, in a "duplicitous relationship," and using him for cover and connections as she developed an influence operation designed to infiltrate powerful political organizations like the National Rifle Association and "advance the agenda of the Russian Federation."

In December, Butina reached a deal with prosecutors, agreeing to plead guilty to charges of conspiracy and cooperate with federal, state and local authorities in any ongoing investigations.

Bamford, best-known as a longtime chronicler of the National Security Agency, met Butina before her arrest and spent time with her during her last few months of freedom. As scrutiny of her activities increased, Bamford began recording their conversations.

"We had a number of long interviews," Bamford told ABC News, "but one time she just never showed up. The next day she apologized and said the FBI had raided her apartment."

Since her arrest, Butina has been held in jail in Alexandria, Virginia, where she continued to speak to Bamford over the phone in collect calls she said were rare instances of person-to-person communication.

"I eat in my cell, I exercise in my cell, I read, I sleep, I do everything," Butina told Bamford. "I am locked for 22 hours. I get two hours at night to do everything including shower."

In his lengthy piece for The New Republic, Bamford is highly critical of both the government's case against Butina and the media's coverage of it. He describes her as "the perfect scapegoat" amid the "anti-Russian fervor" driven by special counsel Robert Mueller's ongoing investigation of Russian interference in the 2016 election.

"The government's case against Butina is extremely flimsy and appears to have been driven largely by a desire for publicity," Bamford writes. "Despite the lack of evidence against Butina, however, prosecutors -- abetted by an uncritical media willing to buy into the idea of a Russian agent infiltrating conservative political circles -- were intent on getting a win. In the context of the Mueller investigation, and in the environment that arose after Trump's election, an idealistic young Russian meeting with influential American political figures sounded enough like a spy to move forward."

Bamford cites, as his primary example of what he deemed "prosecutorial misconduct," the government's headline-making claim that Butina had offered someone sex in exchange for access to a political organization. The explosive allegation drew a sustained and vocal response from Butina defense attorney Robert Driscoll, and prosecutors ultimately were forced to admit they had made a mistake, drawing the ire of the judge.

Butina told Bamford the allegation was devastating both for her and her family back in Russia.

"Me being called a whore ... it's very hard. It's just so much pain for the family," Butina said. "I care about my reputation."

A spokesperson for the U.S. Attorney's Office in Washington, which is handling the case, declined to comment because the case is pending.

But according to John Cohen, who once oversaw all counterintelligence activities at the Department of Homeland Security and is now an ABC News contributor, Bamford's central claim that the government lacks evidence of wrongdoing by Butina might be mistaken.

The primary objective in counterintelligence investigations, Cohen said, is often not to obtain a conviction, but rather to obtain information that can be leveraged elsewhere. In situations where information has been obtained using highly sensitive collection sources and methods, investigators have to make a choice whether using it in a prosecution would risk their discovery.

"There could be information that investigators were aware of but aren't using as part of a prosecution because they don't want to disclose how they got the information and compromise future collection activities," Cohen said. "So to the public it might appear that the only illegal activity was contained in the indictment, but in counterintelligence cases, that's very often not the case."

Butina's future remains unclear. Her boyfriend, Erickson, was indicted last week on fraud charges in an unrelated case in South Dakota, and he reportedly remains the target of an ongoing federal investigation in Washington related to his activities with Butina.

A status conference in Butina's case scheduled for this week was delayed until the end of the month, with her ongoing cooperation cited. According to Butina's attorney, the case, or at least Butina's role in it, soon could reach its conclusion.

"We remain optimistic the parties will be in a position to set a sentencing date at the next status conference," Driscoll told ABC News. "We will request a time-served sentence, so if the judge agrees, she could be home shortly after sentencing."