After Biden's cleanup effort on infrastructure deal, McConnell presses for more

Here are some key questions and answers.

As a group of 10 Republican and Democratic senators got ready to jet out of Washington on Thursday for a two-week recess, breathing a sigh of relief that at long last, a bipartisan infrastructure deal had been struck, some had not even boarded their planes before blowback from Republicans over President Joe Biden's stated intention to link the agreement to a separate, larger package, threatened to sink the just-announced plan.

Then, after a clarifying statement over the weekend from Biden and some fresh optimism from Republican negotiators, the bipartisan deal seems to be back on track.

But on Monday, taking advantage of the shaky political situation for Democrats, Senate Minority Leader Mitch McConnell demanding even more from Biden, insisting that he tell Senate Majority Leader Chuck Schumer and House Speaker Nancy Pelosi to also back down from their plans to tie the packages together.

McConnell's comments, coupled with the lingering confusion from the weekend, leave outstanding questions about whether the deal can withstand competing interests, especially as pressure mounts for Congress to move on infrastructure before the summer ends.

I thought there was a deal?

There was -- until there almost wasn't -- and it's still far from a done deal.

On Thursday, Biden, walked out of the Oval Office to the White House driveway, and flanked by a group of 10 bipartisan smiling senators, announced to reporters they had reached a deal on a $1.2 trillion infrastructure proposal.

The proposal, workshopped by the bipartisan group, would provide funding for core infrastructure such as roads, bridges and waterways, and, it was said, would be fully paid for without raising taxes or instituting user fees like tolls.

The lawmakers hailed the agreement as a glowing example of bipartisanship, and a big win for Biden, who ran on a promise to make across-the-aisle work a Washington mainstay.

But just two hours later, during a late-added White House event to out the deal, Biden told reporters he had no plans to sign the bipartisan deal unless a separate, larger package came to his desk at the same time.

That package, which Democrats have said they intend to move forward with for months, would focus on other aspects of Biden's American Families Plan - things like jobs, housing, and health care. Democrats have said they intend to pass it using a fast-track budget procedure called reconciliation, which allows them to bypass the usual 60-vote threshold necessary to pass bills in Congress.

"If this is the only one that comes to me, I'm not signing it," Biden said, referring to the infrastructure package. "It's in tandem."

To some of the Republicans who had stood with Biden in the White House driveway, this was tantamount to a veto threat. Some threatened to withdraw their support.

The ensuing scramble was so significant that on Saturday, Biden had to issue a somewhat lengthy clarification in which he stated he had no intention of creating the intention of a veto threat.

"I indicated that I would refuse to sign the infrastructure bill if it was sent to me without my Families Plan and other priorities, including clean energy. That statement understandably upset some Republicans, who do not see the two plans as linked," Biden wrote. "Our bipartisan agreement does not preclude Republicans from attempting to defeat my Families Plan; likewise, they should have no objections to my devoted efforts to pass that Families Plan and other proposals in tandem. We will let the American people—and the Congress—decide."

What are moderate Republicans saying now?

On Sunday, several of the Republican senators who met with Biden at the White House on Thursday said that with Biden's clarification, they are confident the bipartisan deal is back on track.

"I was very glad to see the president clarify his remarks because it was inconsistent with everything that we had been told all along the way," Sen. Rob Portman, R-Ohio, told ABC "This Week" co-anchor Jonathan Karl. "It's very clear that we can move forward with a bipartisan bill that's broadly popular not just among members of Congress, but the American people."

But on Monday, McConnell, who is dead-set against opposes the larger package and apparently sensing an opening to divide Democrats, said Biden needed to do more to reassure Republicans.

In a statement, McConnell called on the president to urge Schumer and Pelosi to commit to unlinking the bipartisan plan from a reconciliation package. Both leaders have previously stated they see the two plans moving together on "two tracks."

"I appreciate the president saying that he is willing to deal with infrastructure separately, but he doesn't control the Congress and the speaker, and the majority leader," McConnell said.

Schumer hasn't directly responded to McConnell's call, but in New York on Monday he reaffirmed that he was committed to passing both the bipartisan bill and the reconciliation package.

On Monday, White House press secretary Jen Psaki repeatedly dodged questions about how Biden would proceed, saying he has spoken with lawmakers and will leave the timing of the bills to Congress.

"I know that we're quite focused sometimes on process in here, I understand that the process of a bill becoming a law is important, but the president intends to sign both pieces of legislation into law. He is eager to do that," Psaki said.

Hasn't a second "human infrastructure" spending package always been on the table?

Democrats have been clear for weeks they intend to use a so-called "two-track" approach to getting Biden's infrastructure priorities -- both core physical infrastructure and human infrastructure -- passed this year.

Even though some Republicans have expressed outrage over the tying of the bipartisan bill to the reconciliation tool -- allowing Democrats to pass a budget measure with no GOP votes -- many of the Republican negotiators have been resigned to the fact that Democrats have the right, as the majority party, to pursue reconciliation.

"I cannot control what Democrats do. My gosh, if I could, they wouldn't be Democrats, Sen. Bill Cassidy, R-La., who is part of the bipartisan group of negotiators, said on Fox News last week. "I think we've made progress even if Schumer -- Majority Leader Schumer decides to proceed with another -- a reconciliation bill."

The Senate parliamentarian has already green-lit the use of this procedural move, the same one that was used to pass Biden's massive COVID-19 spending bill in March, for an additional use this year. For Democrats, this next reconciliation package is a major opportunity to move some of Biden's key campaign priorities before the midterm elections.

Some moderate Democrats had been skeptical of pursuing a second reconciliation package to pass "human infrastructure" priorities, though some holdouts, including West Virginia Moderate Democrat Joe Manchin, have recently warmed to it.

However, Democrats are far from united on how expansive this package should be, and all 50 of them will need to be on the same page to pull this off.

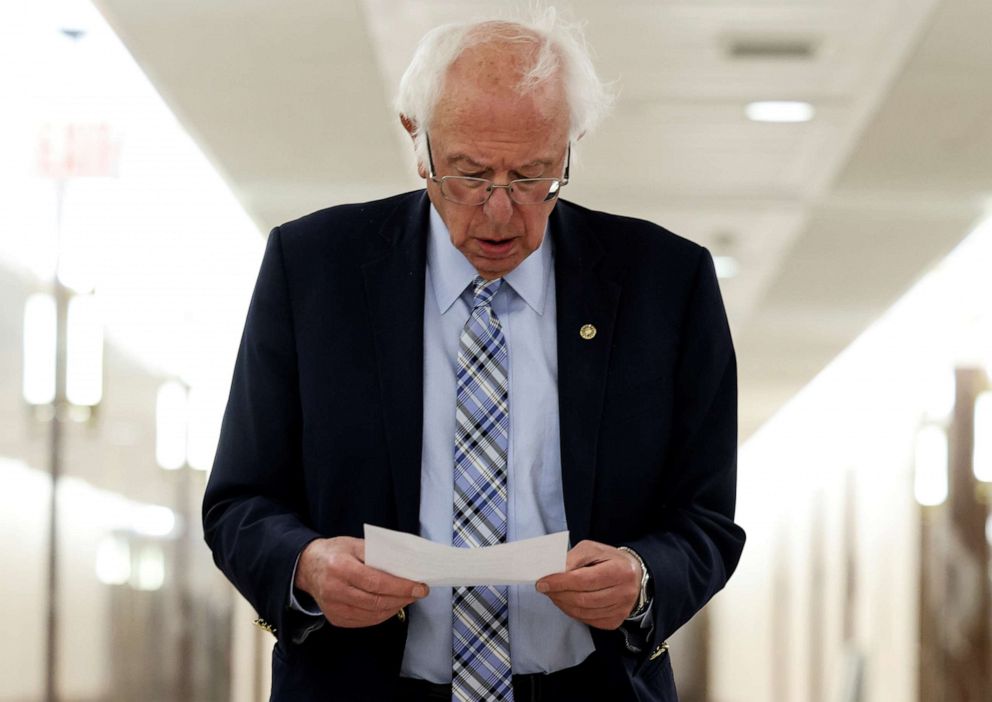

Senate Budget Committee Chairman Bernie Sanders, I-Vt., has said he wants a reconciliation deal costing a staggering $6 trillion. That's almost certainly a non-starter for moderates like Manchin, who on Sunday told Karl he may support reconciliation, but only a package that can be credibly paid for.

"I want to make sure we pay for it. I do not want to add more debt on. So if that's $1 trillion or $1.5 trillion or $2 trillion, whatever that comes out to be over a 10 year period, that's what I would be voting for," Manchin said.

Biden hasn't recently said what he would want in a reconciliation deal, but his American Families plan is worth $1.8 trillion and the White House views a reconciliation package as an opportunity to pass other measures left on the cutting room floor of the bipartisan infrastructure deal.

What about progressive Democrats?

Democratic leadership is walking a very fine line here because, for every Republican who is threatening to withhold support if the bipartisan plan is linked to the bigger spending package, there is a progressive Democrat for whom getting the bigger package is a prerequisite to their supporting the bipartisan package.

"Let me be clear: There will not be a bipartisan infrastructure deal without a reconciliation bill that substantially improves the lives of working families and combats the existential threat of climate change. No reconciliation bill, no deal. We need transformative change NOW," Sanders tweeted on Sunday.

Sen. Elizabeth Warren, D-Mass., said Thursday that "there's commitment in our caucus that one pieces is not going to go forward and leave the rest of it back in the train station." Sen. Kirsten Gillibrand, D-N.Y., told ABC News that commitment to reconciliation is a requirement for her support of the bipartisan bill.

If progressives don't back the bipartisan bill, it could fall short of the 60 votes necessary to move it forward it in the Senate. Even if enough Republicans got behind the bipartisan bill to counteract potential progressive defectors, it's not yet clear if Schumer would bring a bill to the floor that doesn't have broad support within his own caucus.

When do we expect to see movement on these bills?

The exact timing on a path forward isn't entirely clear, but Schumer said last week he plans to bring both the bipartisan infrastructure package and a reconciliation package to the floor when the Senate returns from its two-week July 4 recess.

That timeline may be a bit ambitious. Reconciliation is a multi-step process requiring work by several Senate committees and two open-amendment processes.

Still, Democrats and Biden have been clear they want to move on infrastructure this summer.

So, buckle up for some Washington political drama -- in July.