Despite coronavirus concerns, EPA declines to pursue stricter limits on air pollution

Experts say the science supports more restrictions on pollution.

Despite concerns about a link to more severe novel coronavirus cases, the Environmental Protection Agency will not move strengthen requirements on tiny airborne particles of pollution linked to respiratory and cardiovascular illness, saying the current levels are enough to protect Americans.

EPA Administrator Andrew Wheeler cast doubt on some of the science that supports strengthening the standards for soot from power plants, wildfires and agriculture, saying the EPA believes the current standards protect human health while they look at the research further.

"There's still a lot of uncertainties, and that we believe that the current level that was set by the Obama administration is protective of public health while we continue to look at the uncertainties around (particulate matter)," he said on a call with reporters.

Tune into ABC at 1 p.m. ET and ABC News Live at 4 p.m. ET every weekday for special coverage of the novel coronavirus with the full ABC News team, including the latest news, context and analysis.

Average concentrations of soot or tiny particle pollution have declined almost 40% in the U.S. since 2000, the EPA said in a press release, that also included praise for the announcement from multiple Republican members of Congress.

But several health organizations and experts say the government should allow even less pollution into the air, citing studies and evidence that reducing air pollution could prevent tens of thousands of premature deaths tied to pollution every year.

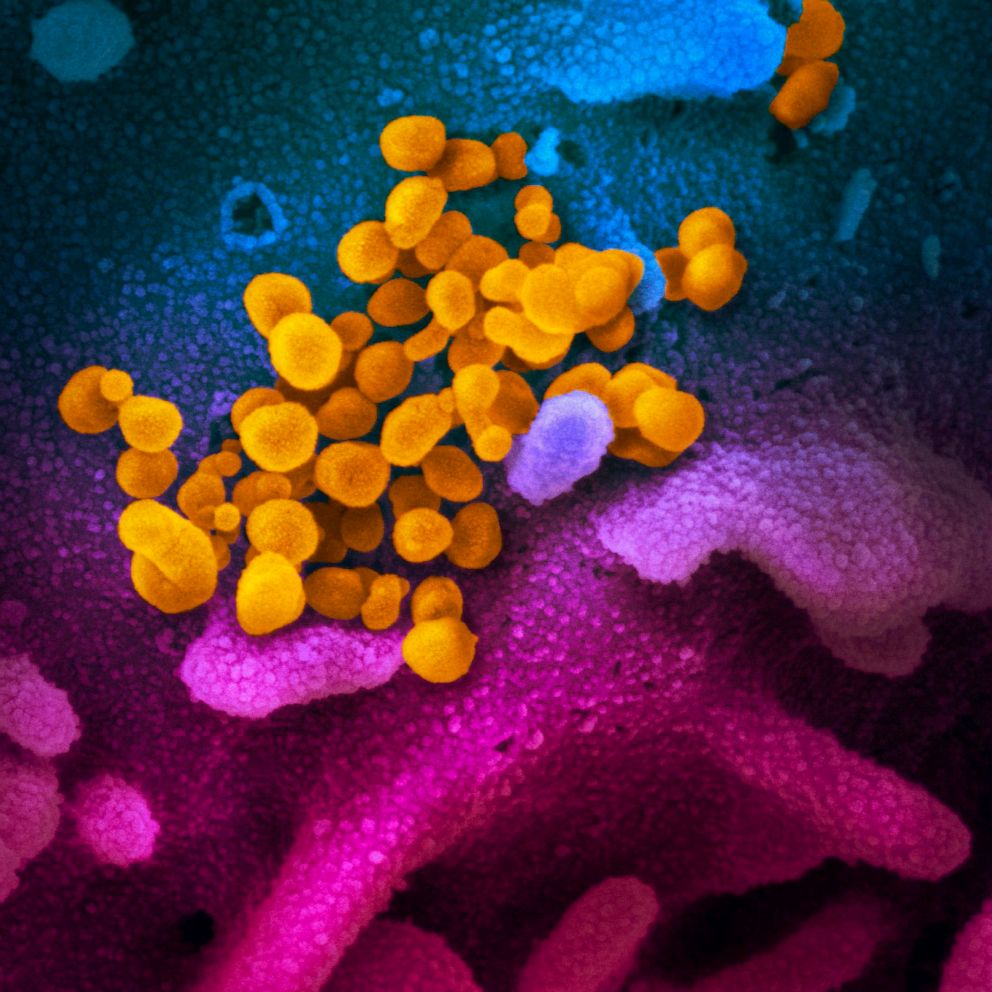

"We fundamentally disagree with the conclusion of the administrator. We think that there is clear and consistent science that supports a significant strengthening of both the annual and 24-hour standards," said Paul Billings, national senior vice president of public policy for the American Lung Association. "We're talking about really small particles, byproducts of combustion and stuff that penetrate deep in the lungs and get past the body's natural defenses. And that can cause a wide range of health effects, healthy adults may cough or wheeze, but these particles are linked to asthma attacks, strokes, heart, heart attacks, exacerbation of obstructive pulmonary disease and new data shows that there's a greater risk of mortality from COVID-19 associated with elevated levels of particle pollution."

The new data Billings referenced is a study released by researchers at Harvard last week that found long-term exposure to more pollution is connected to more severe outcomes from COVID-19 infections.

When asked about that study, Wheeler said the EPA will look at the findings when they have gone through the scientific peer review process but that the agency considers the findings preliminary.

H. Christopher Frey, the Glenn E. and Phyllis J. Futrell distinguished professor of environmental engineering at North Carolina State University and chair of an independent committee that reviewed the science and information around EPA's decision, said they also recommended the EPA lower the level of fine particle pollution that's considered acceptable.

He said EPA's justification for maintaining current air pollution standards is "untrue and nonsensical" and contradicts the findings of the independent board.

"We found unequivocally and unanimously that the current fine particle standard is not adequate to protect public health," Frey told ABC News.

Frey was a member of EPA's clean air advisory panel before it was disbanded in 2018, but the group of experts created an independent panel to continue to evaluate the science and policies around air pollution. He said the administration "rigged the scientific review process" by replacing the experts with a newly appointed panel that he believes would deliver an answer they wanted to hear.

Frey said he doesn't dispute that some uncertainty exists in research about air pollution and its health effects and mortality but that the science does not support statements that the current standard is adequate.

"Policy decisions have to be made before the science is, you know, fully completed. It's an ongoing process so we never fully have complete certainty and also the nature of some of these problems, like we're looking at what's the real world health impact of air pollution on actual people. And that involves data for humans that there's just a tremendous amount of variation and exposures and how each person responds in any way. So there are lots of -- lots of issues that are considered in detail in these assessments," Frey said.

But he added that despite that uncertainty experts are very confident exposure to fine particles causes premature death.

"So even with uncertainty, we have a robust scientific finding that there is a severe public health problem that should be addressed by EPA," Frey said.

When asked about the decision to disband the earlier committee, Wheeler said they had to streamline the review process to meet statutory deadlines but that he doesn't believe that had any negative impact on creating the new proposal.

Wheeler also pushed back on reports that the EPA’s decision to be more flexible about enforcing environmental laws during the pandemic would lead to more air pollution, saying, "There is no emissions increase from our enforcement memo."

Frey said that even though he expects legal challenges to the EPA rule that could spend months or even years in court, the administration has won in getting the least stringent regulation possible until that is resolved.

The EPA proposal will be open for 60 days of public comment and Billings said the public should submit comments calling for more protective standards.

"I think everyone is acutely aware of the fragility of respiratory health of lung health in April, 2020," he said.

What to know about coronavirus:

- How it started and how to protect yourself: coronavirus explained

- What to do if you have symptoms: coronavirus symptoms

- Tracking the spread in the US and Worldwide: coronavirus map