Election experts implore Congress to extend ‘arbitrary’ vote-tallying deadlines

Congressional action could spare a “grave national controversy,” experts said.

While the presidential election will be held on Nov. 3, there are two other dates that campaign officials from both President Donald Trump's and former Vice President Biden's teams have circled on their calendars that could be just as important to the fate of the 2020 race.

This year, under 19th century election law, Dec. 8 is known as the “safe harbor” deadline, the date by which states must submit the winner of the presidential election if they are to be insulated from legal disputes. Six days later, on Dec. 14, Electoral College representatives meet to formally select the next president.

Those little-known December deadlines are rarely meaningful. This year, however, with a pandemic bearing down on the country and a record-setting number of Americans expected to vote by mail for the first time, these dates could attract unprecedented attention and some are calling for them to be delayed to avoid a potential crisis.

“The question here, of course, is – in the middle of the pandemic, with more people voting absentee – are all the states really going to be able to count their vote and have them ready to be sent in by Dec. 8?” said Meredith McGehee, the executive director of Issue One, a nonpartisan ethics watchdog group.

Enshrined in an obscure 1887 law meant to guide the country in the event of a contested election, these “arbitrarily compressed timeframes,” as Adav Noti of the nonprofit ethics watchdog Campaign Legal Center characterized them, are coming under renewed focus ahead of what many state officials worry could become an epic court fight.

Fears of 'debilitating political crisis'

There is so much concern over the possibility of a contested vote, more than 40 legal and election experts wrote to lawmakers last week imploring them to extend both the safe harbor and the Electoral College meeting deadlines into early January.

“In the event of one or more protracted disputes at the state level, the addition of 24 days to the deadline for determining electors could spare the country a debilitating national political crisis,” the letter says.

If the count is unresolved before those key deadlines, the letter says, the nation will be forced to interpret “troublingly ambiguous provisions” of the Electoral Count Act of 1887 that suggest the outcome would fall to a newly seated Congress in the first week of January.

And if it is left “to the new Congress to determine the winner of the electoral votes of one or more states,” the law experts warned it “could produce a grave national controversy just two weeks before the inauguration.”

The idea to provide more time for votes to be counted was being pushed back in August by Sen. Marco Rubio, R-Fla., who proposed extending them by more than three weeks, into early January.

“We cannot escape the pandemic-induced reality of increased mail-in voting, and the logistical challenges associated with it will be difficult for some states to resolve in the next couple of months,” Rubio wrote in a press release announcing the proposal. “We should give states the flexibility to provide local election officials additional time to count each and every vote.”

The Electoral Count Act traces back to the aftermath of the contested presidential election of 1876, in which Republican nominee Rutherford B. Hayes edged out Democratic contender Samuel Tilden in one of the most hotly disputed elections in the nation’s history.

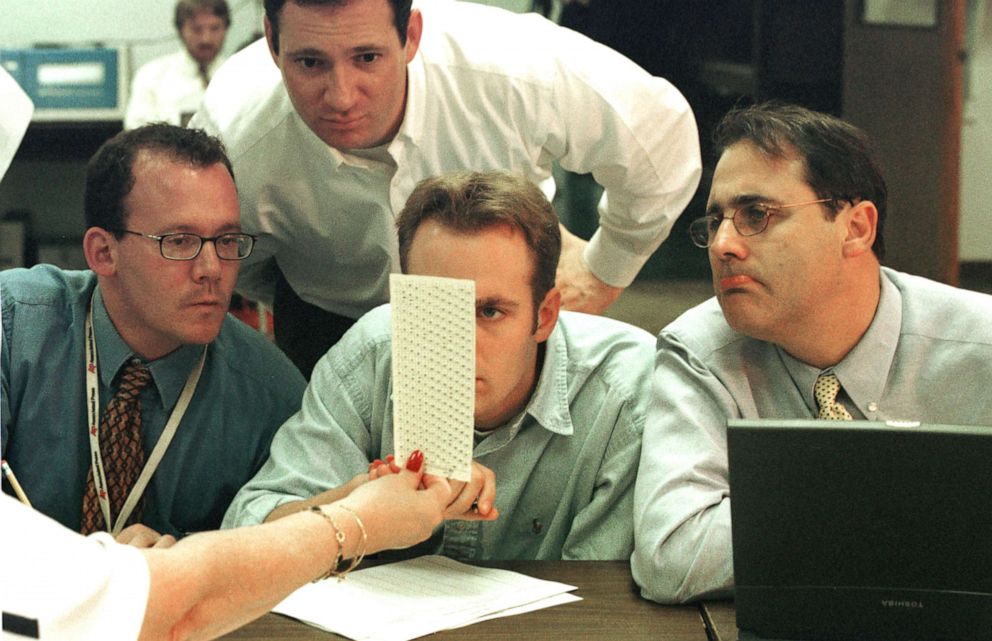

For many election experts who have expressed concern, their fears are grounded in the chaos that ensued during the contested presidential election in 2000, when it fell to the U.S. Supreme Court to resolve the Florida vote count. The court cited the safe harbor deadline in part to justify its decision to end the state recount – a point disputed by both the late Justice Ruth Bader Ginsburg and Justice Stephen Breyer in their dissents.

In August, after Rubio introduced his bill, McGehee and other election reform leaders embarked on a lobbying effort to sway congressional offices to support its passage. Despite raising concerns with the logistical pressures of widespread vote by mail, experts said, the effort stalled and Rubio’s bill never moved forward.

“The consequences of people voting by absentee was clear from the get-go,” McGehee said. But over the summer, she continued, “it was very difficult for congressional offices to believe that we would reach November and the pandemic would not have subsided.”

Lawmakers had “very little questions about the substance of [Rubio’s] bill,” but were skeptical of the political implications of perceptions that it would mean “changing the rules this close to the election.”

Hit a snag

Efforts to extend the December deadlines to January hit an additional snag when President Trump began calling into question the viability of vote-by-mail and even suggested delaying the election. McGehee said that sort of “hanky-panky” surrounding the upcoming election – including repeated and unfounded claims by the president of widespread fraud – has spooked lawmakers. Others involved in the lobbying effort agreed.

“The whole thing came off the table when the president started talking about delaying the election, which is really unfortunate,” said Noti, of the Campaign Legal Center, lamenting how the “common sense” deadline extension “got caught up” in Trump’s political firestorm.

Despite a consensus among experts that extending the safe harbor deadlines would help states avoid a constitutional crisis, Aaron Scherb, the legislative director at the nonpartisan ethics group Common Cause, said any change could hold “unintended consequences.”

“We think, given the president’s previous remarks … it could be misconstrued by the president as Democrats trying to ‘rig’ the election,” he said.

Scherb argued Congress could wait until after the election and then consider extending the deadlines. But that approach did not sit well with the 40 election law scholars who wrote to Congress.

“Congress should not wait for a crisis to emerge,” they wrote, “but should preempt the crisis by legislating in advance.”