As a presidential candidate, Sen. Harris -- a lawyer -- struggled to present a clear case: ANALYSIS

She could never define for voters what her presidency would look like.

Kamala Harris was elected to the Senate the same day President Donald Trump won the White House. As soon as she got to Washington, there was buzz she would likely run to take him on in 2020.

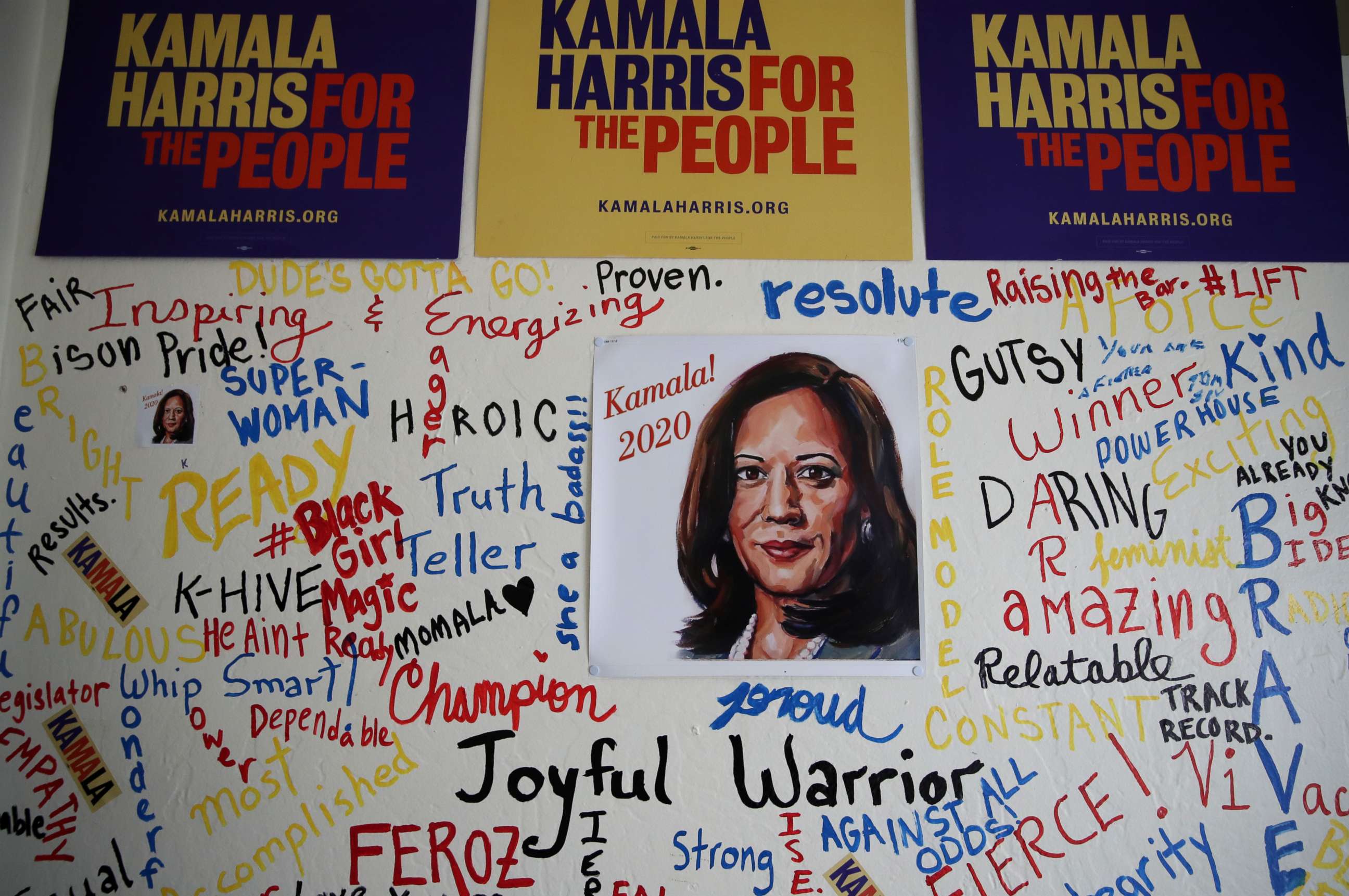

Democratic Party leaders loved the concept of a Harris candidacy. An African American woman as the next potential nominee would be a bold, defiant choice after Hillary Clinton's presidential loss -- a chance to tell the country that their party was not backing down, but standing up in some way.

Her candidacy symbolized, albeit in maybe a simplistic way, the urgency Democrats feel around needing to reenergize diverse constituencies and the new face they hope to present the country.

Add in her smarts, charm and prosecutor bona fides, and it was easy to see why so many former Clinton campaign alums ended up on her staff.

Harris' campaign launch was easily one of the strongest this cycle. The impressive Oakland, California, crowd, the commanding speech and the coordinated rollout had all the markings of a team in tiptop shape and a candidate who knew what she was doing. The prospects of her winning her home state -- as many candidates are expected to do -- left her at the top of political number-crunchers' lists.

Winning hundreds of delegates in California, in a year where the state is so early in the cycle, could have been a game-changer. But as her chances of taking her home state looked less likely, she focused instead on Iowa. The Midwest, though, was far from a natural fit for her.

Starting off with high expectations can be a curse -- cue former Texas Rep. Beto O'Rouke. And in a crowded field, clear ideas and simple messaging are winning out -- just ask Massachusetts Sen. Elizabeth Warren, whose campaign start was one of the rockiest of the bunch.

In 10 1/2 months of formal campaigning, Harris -- the lawyer -- struggled to present a clear case.

Why was she different than the candidate next to her? She could never define for voters what exactly a Harris presidency would look like. Sure, she would be a Democrat in the White House, but running on a sweeping list of party priorities, it started to seem like she was running on little at all, or at least little that was distinctive from her many peers.

Harris was also caught in a few tough flip-flops and wishy-washy answers early on, and did few sit-down interviews.

After first signing on to Vermont Sen. Bernie Sanders' "Medicare for All" legislation in Congress, she tripped and stumbled when trying to walk back her support of the bill. Then, at the first Democratic debate in June, she raised her hand to a question about who would be comfortable eliminating private insurance. She backtracked after the fact, said she misunderstood the question, and promised to put out a plan of her own.

When she did lay out a plan -- trying to find a middle ground between a potential single-payer health care system and one that let many private insurance plans remain on the market too -- several health care experts were left scratching their heads. New York Magazine's headline read, "Kamala Harris's Medicare For All Plan Makes No Sense."

Time and again, voters reward candidates who stick to their guns and present clear values. Conviction on the issues can matter even more than the issues themselves.

But beyond questions dealing with health care, Harris hedged a lot of her answers in the spring and summer. When Warren pitched breaking up Facebook, Harris said, "I think we have to seriously take a look at that."

When she was asked about a controversial statement from Sanders -- that incarcerated felons should be able to vote -- she said, "I think we should have that conversation" and added, "I'm going to talk to experts and I'm going to make a decision and I will let you know."

As a former prosecutor, it was surprising when she did not have an outright opinion on some policies like legislation to ban chokeholds. And where she may have been able to create a compelling narrative around her evolution on drug crime sentencing and some specifics in criminal justice reform -- after all, a lot of politicians have moved on the issue of marijuana legislation, for example -- she instead faced skepticism from some younger African American voters about her role in law enforcement.

Harris' memorable moment on at second debate was the high point of her candidacy. She took on Joe Biden directly and personally on an issue from his past dealing with race.

"There was a little girl in California who was part of the second class to integrate her public schools and she was bused to school every day. And that little girl was me," she said.

And in that moment it looked like she had leagues ahead of the former vice president, speaking to the country today and making him look like a part of the past.

Her polling numbers shot up, but settled back down quickly. Over time she started to sound only one note on the stage. Her takedowns were masterful, but perhaps voters were craving someone who could build them up instead.

As her campaign plateaued, Harris's stump speech became even more about Trump.

Ironically, with the exception of Biden -- yes, a big exception -- the other front-runners have spent a lot less time talking about the president or why they are best suited to take him on. They talk about their visions instead.

Harris questioned whether her lagging poll numbers meant that Democratic voters, perhaps unfairly, were assuming it would be hard for her to win nationwide. During an interview with Axios this fall, she called her electability the "elephant in the room."

She had qualified for the next debate, making the timing of her exit surprising. As it happens, several candidates of color have not yet made the cutoff.

Yvette Simpson, CEO for Democracy for America and an ABC News political contributor, argued that candidates of color can face both concern among voters about whether they can lead as well as skepticism about whether they can win.

"It is a real catch-22," Simpson said. "Issues of perceived electability are real. ... A lot of voters want to see if you can win before they will jump on board and help you win."

Simpson argued that Harris also did not pick a lane in a race that is defined by policy lanes.

"She shifted more into a corporate, moderate Democrat lane and lost a lot of progressive support because of it," Simpson said. "And she was judged more harshly than others. … Candidates of color have had a harder time taking on Biden in this race. Somehow Mayor Pete (Buttigieg) is automatically assumed to be the one to carry Biden's mantle forward -- why?"