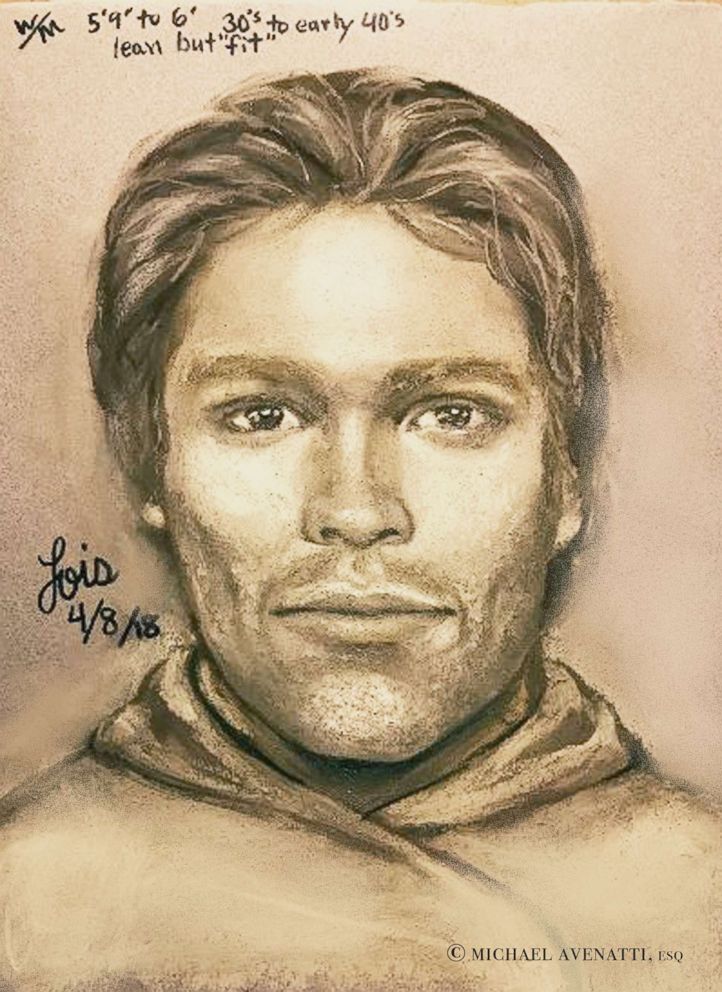

Sketches like the one released by Stormy Daniels are 'like a Hail Mary pass,' law enforcement experts say

Comes after Stormy Daniels released sketch of man who allegedly threatened her.

Stormy Daniels released a sketch of a man she says threatened her seven years ago. Even though the artist responsible for the sketch has the Guinness World Record for most identifications by a forensic artist, this case isn’t going to join those ranks, law enforcement experts say.

The adult film star, who has accused the unidentified man of threatening her to stay quiet about an alleged affair she had with President Donald Trump, claims the alleged incident happened in 2011. This means that when she sat down with a sketch artist recently, the incident would have been nearly a decade old.

David Brown, the former chief of the Dallas Police Department, said that composite sketches aren't always accurate even in the best of circumstances when the details of a suspect or person of interest are at the top of one's mind.

“Normally, when you’re putting out a composite sketch to the public it’s a little bit of a Hail Mary pass because you don’t have any other leads or suspect information and you’re soliciting the public’s help in finding a suspect,” said Brown, who is now an ABC News consultant.

While composite sketches are a commonly accepted tool and are used by the FBI and some of the country’s top police departments, they aren’t widely seen as an extremely accurate tool.

“In the world of sketch artists, the estimates are that less than 10 percent appear to be effective,” said Brad Garrett, a former FBI profiler, and current ABC News consultant.

How sketches are made

The talent of sketch artists extends beyond their work on the page, Garrett explained.

“The really good ones are terrific interviewers because that’s what you need to be,” he said, noting how artists will spend hours with a witness or victim, sometimes almost immediately after the crime occurs, meaning that they may have to spend time “consoling and calming” the individual down.

Many begin by asking the person to start recalling details before the alleged incident, he said, with questions about what time they woke up, or what they had for breakfast, or what their children wore to school that morning.

“[They] walk them through until they feel comfortable,” he said.

Once the attention turns to describing the attacker or suspect, the sketch artist will ask the individual to “try to focus on a particular aspect” of the suspect’s face, and then go into details on that before expanding outward. For example, Garrett said if the artist started by asking about the suspect’s eyes, they would ask about their eye color, if their pupils were large or small, if they saw the whites in their eyes, and then they would expand out to their eyebrows and their nose and then the rest of their face.

After that thorough questioning, many sketch artists have a copy or a version of something called the FBI picture book, which is filled with “photos of non-suspects,” Garrett said. The individual then pieces different parts together, looking at different features from the different photos that match those descriptions.

Even in the best of circumstances, when details of the person of interest or suspect are plentiful, it’s not expected to be identical.

“Good sketch artists would tell you the following: ‘I’m trying to get you a resemblance of the person you saw, it’s not like a photograph,’” Garrett said.

The sketch released by Stormy Daniels’ lawyer

As for the sketch that Daniels and her lawyer Michael Avenatti released on “The View” on Tuesday, law enforcement experts were not optimistic about the chances of finding the alleged perpetrator.

John Cohen, a former acting Homeland Security undersecretary who has 32 years of law enforcement experience, said that the passage of time will undoubtedly impact the accuracy of the sketch.

“It’s difficult for me to believe that there wasn’t at least some fading of memory or the image you have in your mind being conflated with other images that you have in your mind,” said Cohen, who is now an ABC News consultant. “On the other hand, if this occurred as she described, it probably was a very horrifying event and in situations such as that I’ve seen witnesses or victims maintain a very clear image in their mind.”

For Brown, the bigger concerns stem from the lack of memorable or unique characteristics of the alleged perpetrator’s face.

“I don’t know how helpful this will be -- I think there’s zero chance this will help identify the person,” Brown said.

“This is a pretty generic sketch. There's no tattoos or unique markings or distinctions on the person that would single them out, so it would be tough for the public to say they know who that person is,” he said, adding. “It’s not helpful without some unique identifiers in the composite sketch.”