Temperatures and carbon dioxide are up, regulations are down: Environmental headlines you missed this week

May set a record for above average temperatures and CO2 is at an all-time high.

Every week we'll bring you some of the climate change news and environmental headlines you might have missed this week.

This is "It's Not Too Late" with ABC Chief Meteorologist Ginger Zee. On ABC News Live and abcnews.com.

May sets records, July likely to be extra hot

Spring 2020 set records as this May was tied with 2016 for the warmest May on record in 141 years -- 1.71 degrees above average.

It also marked the 425th consecutive month, or 35 years, that temperatures were above average.

And the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration says that trend isn't likely to stop with most of the U.S. facing the likelihood of a hotter-than-average summer going into July.

Don't let the pandemic fool you, CO2 is at an all-time high

Despite reports early in the pandemic that keeping everybody at home led to reductions in pollution and wildlife reclaiming the streets, the gas that traps heat and adds to those record-high temperatures is at an all-time high.

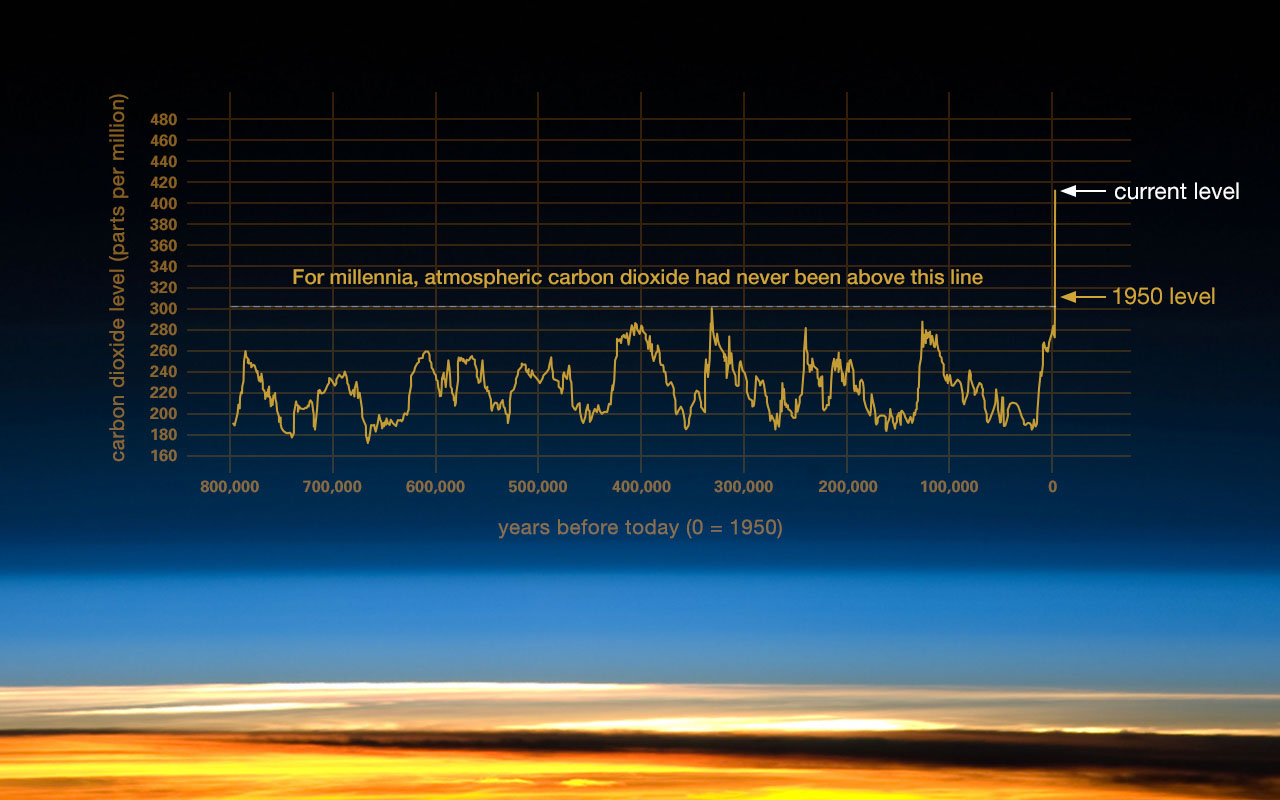

Carbon dioxide reached its highest level in 800,000 years, according to NASA.

If levels continue to rise, the climate could face more above-average temperatures and other changes that would become more difficult to reverse.

Trump finalizing changes to 'magna carta' of environmental law

The COVID-19 pandemic and Black Lives Matter protests in recent weeks and months have increased attention on inequality in the country.

And at the same time the country is talking about dismantling systemic racism, environmentalists are concerned that a bedrock environmental law created to protect Black and brown communities from being taken advantage of is under threat.

The National Environmental Policy Act, or NEPA, requires the federal government to consider the impact projects like highways, bridges and pipelines have on the environment and the communities where they will be built.

In the late 1960s, as the great white flight was taking place out of cities and to the suburbs, the government started to plan giant freeway projects, many of which would have required demolishing parts of majority Black and brown neighborhoods in cities including Atlanta and Washington, D.C.

Those proposed freeways sparked protests nationwide -- eventually leading to the NEPA, a formal way citizens could express their opinion about projects in their community.

President Richard Nixon signed the NEPA into law in 1970, at a time when the country saw significantly more pollution because agencies like the Environmental Protection Agency didn't exist yet.

President Donald Trump and his administration say that the NEPA has slowed down infrastructure projects by requiring years and years of study and prompting lawsuits from outside groups.

On June 4, Trump signed an executive order to waive the NEPA and other laws, citing the need to boost the economy after the impact of the pandemic.

"From day one, my administration has made fixing this regulatory nightmare a top priority," he said at the signing.

The order says agencies can decide to bypass the NEPA, the Endangered Species Act and other laws to start projects immediately, but there's some disagreement about how much of an impact it will have because federal agencies haven't released information on which projects could be affected and if it could be challenged in court.

But environmental advocates say they're more concerned about changes to the NEPA the administration has been working on for a while because the White House Council on Environmental Quality has proposed changes that would alter the law permanently.

Environmental advocates say they're concerned those changes could lead to more projects that add to climate change -- causing emissions and take away the voice of Black and brown communities who are impacted by pollution the most.

The proposed changes would require that environmental impact statements are completed in a set amount of time and in some cases limited to a certain page limit.

It would also change how agencies handle public comments, because a key part of the NEPA is requiring the government to make the public aware of its plans and giving the community a chance to weigh in.

Critics of the change say the changes would make it more difficult for objections to a project to have an impact by requiring comments to be more narrow and specific and discounting concerns about a project like a highway or pipeline's impact on climate change.

Environmental advocates say construction of the wall at the southern border is already an example of what happens when the NEPA isn't available as a way to object to government projects.

"To put it simply, none of the wall construction we're seeing right now would be possible if NEPA was in place -- and most certainly not the massive groundwater extraction, saguaro destruction and blasting and bulldozing of Indigenous, sacred sites," Laiken Jordahl, from the Center for Biological Diversity, told ABC News.

Dozens of industry groups support changes proposed by the Trump administration, including the American Gas Association, National Miners Association, Wind Energy Association and even the American Sheep Industry Association.

The U.S. Chamber of Commerce is one of them, saying that improving the NEPA will make it easier for projects to get approved, including expanding industries like wind and solar energy.

"If we as a nation want be prepared to meet the challenge of climate, and to build an economy for the future. We've got to have a permitting process that allows us to do that," Marty Durbin, president of the Chamber of Commerce's Global Energy Institute, told ABC News.

Durbin said it's not about ignoring environmental advice, simply streamlining the process.

"There's simply no reason right now to have a system that takes more than seven years to even get a yes or no answer on whether you can build a newer, improved highway," he said.

The Office of Management and Budget has indicated that the proposed changes to the NEPA are in their last stages, meaning the final rule could be announced at any time.

Groups like Earthjustice said they plan to sue to challenge the changes as soon as they become final and other experts said there could be a push for Congress to ensure environmental reviews and public comment are part of any federal project.