California's 'trillion dollar' mega disaster no one is talking about

There's a push to prepare for flooding that could hit parts of the West Coast.

Disasters typically associated with the West Coast include devastating earthquakes and out-of-control wildfires, but there's an epic disaster that could be far worse than both -- and it could happen at any point.

Officials and experts call it the "ARkStorm," and it is the other "big one" few are talking about.

With California's 2020 rainy season now underway, imagine almost a month of drenching storms along the entire West Coast.

The state would be swallowed in 10 to 20 feet of rain.

At up to 200 inches in some places, floods would hit nearly every major population center in the state.

The sheer amount of rain means parts of the San Francisco Bay area, Los Angeles, San Diego and Sacramento would all be underwater. It would cause thousands of landslides, major dam failures and decimate the state's entire agriculture industry.

It might sound like a scene from a post apocalyptic movie, but this type of storm is not only possible, it's happened before.

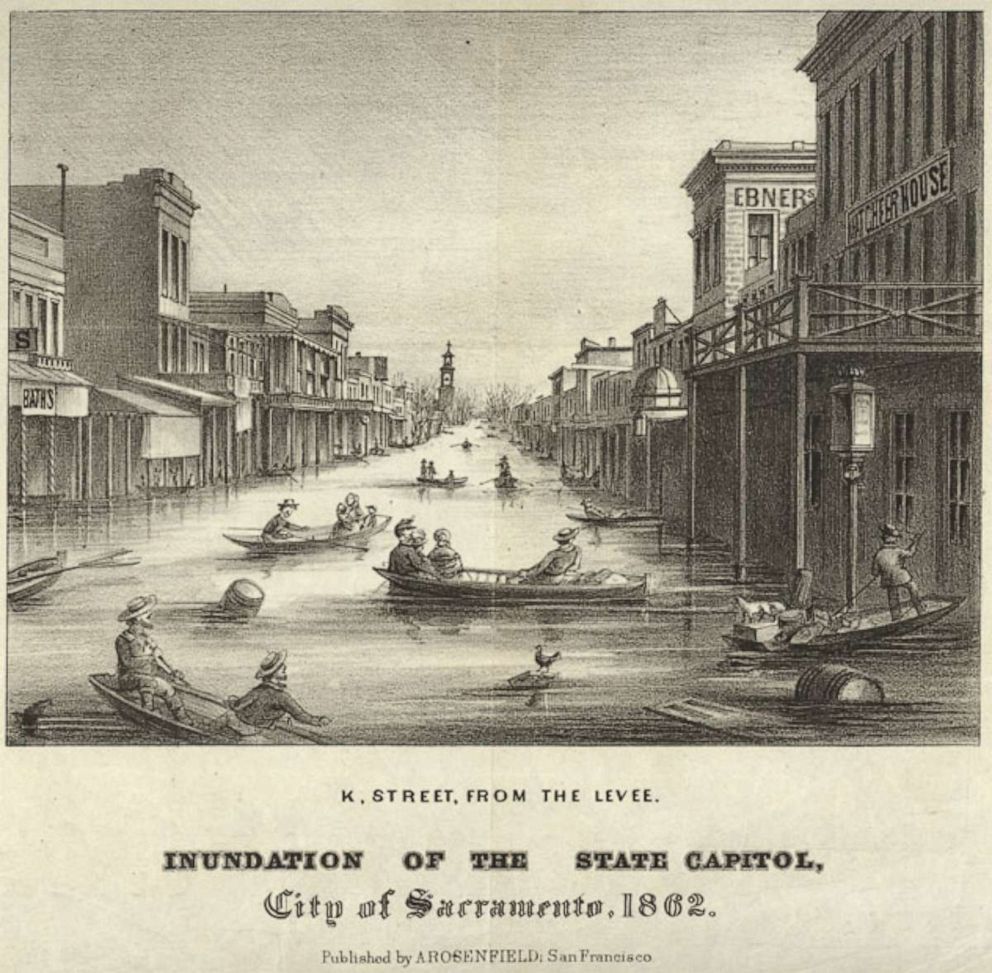

California's deadliest and most-destructive natural disaster in recorded history, a so-called "mega storm," hit the state in the winter of 1861 and 1862.

"My family came to California in the 1870s. And the really biggest storm was the 1860s, and I had never heard of it," Dr. Lucy Jones told ABC News.

Jones worked as a seismologist at the U.S. Geological Survey for 33 years and has spent the better part of her life helping communities and leaders prepare for inevitable disasters.

The deadly storm of 1861 and 1862 fundamentally changed California.

"The flood flooded a quarter of the homes in California. ... It destroyed one-third of the taxable land of California in that year, and it bankrupted the state," Jones said.

It was so bad the state had to temporarily move the capital away from Sacramento.

"This was a multiweek, extreme precipitation and flood event that essentially filled up a significant portion of the Central Valley with flood water, creating an inland sea, supposedly 40 miles wide and 150 miles long," UCLA Climate Scientist Daniel Swain said.

Swain believes roughly 1% of the state's 400,000 people died -- but there is no official number of casualties.

Jones and Swain have been sounding the alarm for about a decade about what could happen if a similar storm happened today.

"Our model that we did we called the ARkStorm. It was actually raining for about 25 days. And that was enough to flood one-quarter of the property in California," Jones said.

The model published nine years ago serves as a warning to local and national leaders about a scenario that will become reality one day.

"This is very much a trillion dollar-type disaster that we're talking about. So this is on a really high level, in terms of what the long-term consequences would be from California," Swain said.

The model predicts "substantial loss of life" and at least 1.5 million Californians would have to be evacuated from their homes.

California's Office of Emergency Services has spent years developing plans for "mega storms."

"Flood risk is not something that was an unknown to us. California has a long history of widespread floods," Tina Curry, the deputy director of Cal OES, told ABC News.

A quarter of the buildings in the state could flood, with the impact especially catastrophic as only 12% of California property is insured for flooding.

"Individuals need to know what their risks are, know where you live and and have a plan for your family to manage an emergency and be able to get the instructions from your local leadership," Curry said.

Jones and Swain warned that a storm like this is not a freak event -- it is inevitable.

Tree rings and rocks show six "mega storms" more severe than the 1861-1862 storm in the last 1,800 years.

Swain said recent evidence suggests a "mega storm" happens about once every 200 years, meaning in theory the next "big one" could happen at any point in the next 40 years.

Unlike earthquakes and wildfires, it is a little easier to predict a massive rain event, but more challenging to prepare.

"It's very difficult to prepare in many ways, and we have, you can argue, that we've made it worse, because we put in our flood control, and then we built underneath the flood control. So we have a lot of homes sitting in floodplains protected by levees," Jones told ABC News.

The levees protecting those homes are designed for a 75-year flood event, not a "mega storm."

And how bad the next "mega storm" might be, and when it might take place, is in flux because of climate change.

Scientists warn the initial ARkStorm simulation is a cautious scenario; the reality of the next "mega storm" could be far worse.

Swain and his team are working on a new ARkStorm simulation. "We're sort of in the thick of it right now; we're ready to press go on some of these simulations and get cranking," he said.

The original model from 2011 did not take climate change into account, something Swain said could make the next ARkStorm even worse than the flood of 1861 and 1862 and more frequent than every 200 years.

Cal OES is now taking climate change into account in all of its planning for disasters. "We absolutely have done a lot of work to consider the effects of climate change on all of this," Curry told ABC News.

If 1% of California's population died today as a result of a new ARkStorm that would be roughly 395,000 people -- easily the worst natural disaster in U.S. history.

The February 2017 Oroville Dam scare -- when 180,000 people were evacuated due to fears it would collapse -- was a wakeup call for emergency planning. "Every event, including Oroville, is an opportunity to reflect on what we've had planned for, what actually happened and make improvements," Curry said.

The days of rain nearly caused the aging dam infrastructure to fully fail, which Swain said would have likely unleashed a "30-foot wall of water."

A trillion-dollar ARkStorm disaster could also send the entire government deeper into debt, and cripple the state's agriculture, tourism and entertainment industries, according to Swain.

Since California grows a majority of our country's crops, the impact would be felt across the entire country.

Planning for these types of long-term disasters is a key responsibility of government, Jones said.

"That's one of the roles of government, and it's a challenge because politicians are [in office for] very short timeframes, because they're elected," she said. "But what government needs to be doing for us is being the guarantor of the future."

"It's not something that has to be scary necessarily," Curry said. "If you have information, if you have the tools that you need to to plan and prepare, then we can do a lot to keep California safe."