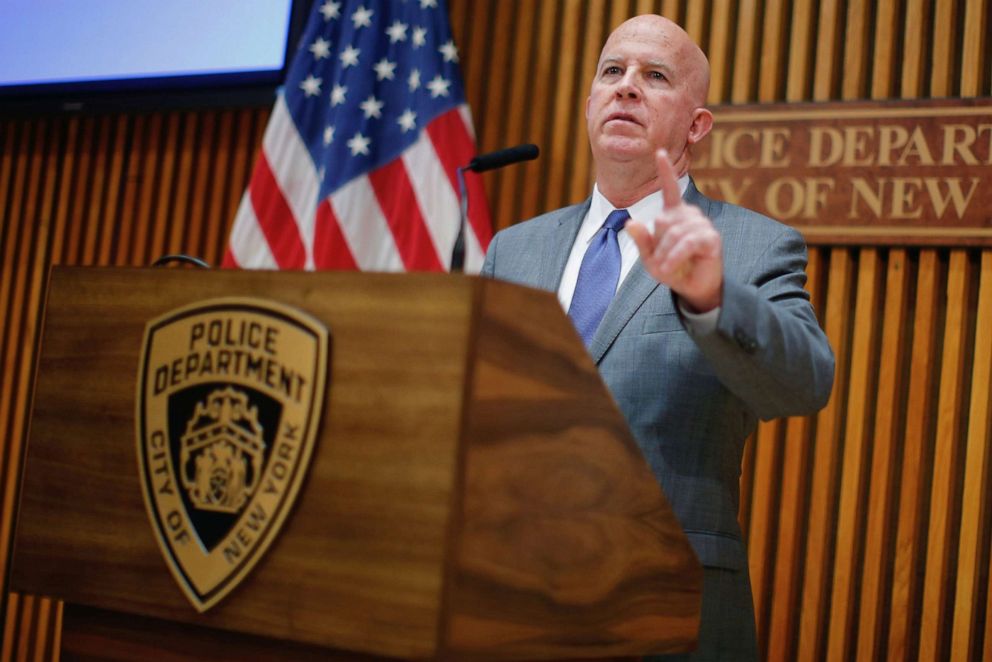

Eric Garner case: NYPD Police Commissioner James O'Neill's speech regarding firing Daniel Pantaleo

Police Commissioner James O'Neill made his announcement Monday.

New York Police Department Commissioner James O'Neill announced on Monday the decision to fire the police officer, Daniel Pantaleo, who was seen putting Eric Garner in a chokehold before he died.

That 2014 incident, which led to Garner's death, prompted outcry against the police, but it wasn't until Monday that O'Neill announced Pantaleo was fired.

Over the past five years, Pantaleo has been working on desk duty. O'Neill announced that he will be immediately terminated, allowed to keep any contributions he put into his pension, but will not be able to keep the vested pension.

Here is the full text of O'Neill's speech as prepared for delivery:

Good afternoon, everyone.

Today, I’m here to announce my decision in the disciplinary case of Police Officer Daniel Pantaleo, who is accused of violating NYPD policy while helping effect the lawful arrest of Eric Garner in Staten Island on July 17, 2014.

It is a decision that necessarily requires fairness and impartiality for Mr. Garner, who died following that encounter with police. It is also a decision that requires fairness and impartiality for Officer Pantaleo, who was sent by this department to assess a situation and take appropriate police action.

First, I will discuss how I reached my decision, and then I will answer any questions you have on this topic.

For some time prior to July 17, 2014, neighborhood residents purposely avoided the area in and directly around Tompkinsville Park in Staten Island. The conditions at that time arose from an array of criminal activity: Drug dealers worked the edges of the park, and across the street, selling narcotics. A handful of men regularly sold loose cigarettes made cheaper by the fact that New York State taxes had not been paid on them. A liquor store nearby sold alcohol to people who would drink that alcohol in the park – people who would sometimes use drugs, urinate, and pass out on benches there.

That summer, the week before, there had been reports of theft and two robberies in the park. There were 911, 311 and other complaints from residents and merchants on an ongoing basis. In some cases, warnings or summonses were issued. In other cases, arrests were made.

And that was the situation at Tompkinsville Park on the day Officer Pantaleo was sent with another officer to conduct an enforcement operation. When the second officer observed Mr. Garner hand out cigarettes in exchange for money, they approached Mr. Garner to make an arrest. That offense could have resulted in a summons, but Mr. Garner refused to provide identification, which meant he would have to be brought to the precinct for processing.

For several minutes on the widely-viewed video, Mr. Garner makes it abundantly clear that he will not go willingly with the police officers.

He refused to cooperate with the arrest and to comply with lawful orders. The video also makes clear that Officer Pantaleo’s original efforts to take Mr. Garner into custody were appropriate – in that he initially attempted two maneuvers sanctioned by the police department.

Officer Pantaleo first grabbed Mr. Garner’s right wrist and attempted an arm-bar technique in preparation for handcuffs to be used. Mr. Garner immediately twisted, and pulled and raised both of his hands while repeatedly telling the officers to not touch him. Officer Pantaleo then wrapped his arms around Mr. Garner’s upper body.

Up to that point in the tense and rapidly-evolving situation, there was nothing to suggest that Officer Pantaleo attempted to place Mr. Garner in a chokehold. But what happened next is the matter we must address.

The two men stumbled backward toward the large plate-glass window of the storefront behind them, and Officer Pantaleo’s back made contact with the glass, causing the window to visibly buckle and warp. The person videotaping the episode later testified at the NYPD trial that he thought both men would crash through the glass. It is at that point in the video, that Officer Pantaleo is seen with his hands clasped together, and his left forearm pressed against Mr. Garner’s neck in what does constitute a chokehold.

The NYPD court ruled that while certainly not preferable, that hold was acceptable during that brief moment in time because the risk of falling through the window was so high. But that exigent circumstance no longer existed, the court found, when Officer Pantaleo and Mr. Garner moved to the ground.

As Mr. Garner balanced himself on the sidewalk on his hands and knees, Deputy Commissioner of Trials Rosemarie Maldonado found that Officer Pantaleo “consciously disregarded the substantial and unjustifiable risks of a maneuver explicitly prohibited by the department.”

She found that during the struggle, Officer Pantaleo “had the opportunity to readjust his grip from a prohibited chokehold to a less-lethal alternative,” but did not make use of that opportunity.

Instead, even once Mr. Garner was moved to his side on the ground “with his left arm behind his back and his right hand still open and extended, [Officer Pantaleo] kept his hands clasped and maintains the chokehold. Mr. Garner’s obvious distress is confirmed when he coughs and grimaces.”

Moreover, Trials Commissioner Maldonado found that Officer Pantaleo’s conduct caused physical injury that meets the Penal Law threshold, and that his “recklessness caused multi-layered internal bruising and hemorrhaging that impaired Mr. Garner’s physical condition and caused substantial pain and was a significant factor in triggering an asthma attack.”

For all of these reasons taken together, even after reviewing Officer Pantaleo’s commendable service record of nearly 300 arrests and 14 departmental medals earned leading up to that day, Trials Commissioner Maldonado recommended that he be dismissed from the NYPD.

“In making this penalty recommendation,” she wrote, “this tribunal recognizes that from the outset Mr. Garner was non-compliant and argumentative, and further notes that the Patrol Guide allows officers to use ‘reasonable force’ when necessary to take an uncooperative individual into custody. What the Patrol Guide did not allow, however, even when this individual was resisting arrest, was the use of a prohibited chokehold.”

As you know, a number of external authorities have asked many of the same questions we have about this incident:

On August 19, 2014, about a month after Mr. Garner’s death, the Staten Island District Attorney’s Office announced it would empanel a grand jury and present evidence on the matter. On December 3, 2014, those 23 Staten Island residents voted to not indict Officer Pantaleo, clearing him of criminal wrongdoing.

That same day, the United States Attorney General announced that the U.S. Department of Justice would conduct its own investigation into Mr. Garner’s death, and weigh bringing federal civil rights charges against Officer Pantaleo.

In the intervening years, the Justice Department made ongoing requests to the NYPD – asking us to delay our internal disciplinary process until its civil rights investigation was complete. And we honored those requests as their process stretched from one administration to the next, with no action by federal prosecutors.

And so, on July 21, 2018, we decided to begin NYPD proceedings. Members of the public, in general, and Mr. Garner’s family, in particular, had grown understandably impatient. The trial began on May 13, 2019.

On July 16, 2019 – one day before the five-year statute of limitations expired, the Justice Department announced it would not file federal charges against Officer Pantaleo.

Then, on August 2, 2019, with Officer Pantaleo’s NYPD trial concluded, Trials Commissioner Maldonado ruled that: “[Officer Pantaleo’s] use of a prohibited chokehold was reckless and constituted a gross deviation from the standard of conduct established for a New York City police officer.”

After noting that Officer Pantaleo had admitted he was aware that chokeholds are prohibited by this department, she further concluded:

“With strongly-worded and repeated warnings about the potentially lethal effects of chokeholds found throughout multiple sections of the training materials, it is evident that the department made its 2006 recruits keenly aware of the inherent dangers associated with the application of pressure to the neck. Given this training, a New York City police officer could reasonably be expected to be aware of the potentially lethal effects connected with the use of a prohibited chokehold, and be vigilant in eschewing its use.”

From the start of this process, I was determined to carry out my responsibility as police commissioner unaffected by public opinions demanding one outcome over another. I examined the totality of the circumstances and relied on the facts. And I stand before you today confident that I have reached the correct decision.

But that has certainly not made it an easy decision.

I served for nearly 34 years as a uniformed New York City cop before becoming Police Commissioner. I can tell you that had I been in Officer Pantaleo’s situation, I may have made similar mistakes. And had I made those mistakes, I would have wished I had used the arrival of back-up officers to give the situation more time to make the arrest. And I would have wished that I had released my grip before it became a chokehold.

Every time I watched the video, I say to myself, as probably all of you do, to Mr. Garner: “Don’t do it. Comply.” To Officer Pantaleo: “Don’t do it.” I said that about the decisions made by both Officer Pantaleo and Mr. Garner.

But none of us can take back our decisions, most especially when they lead to the death of another human being.

I was not in Officer Pantaleo’s situation that day. I was chief of patrol and, later that year, chief of department. In that position, I proposed our Neighborhood Policing model so that the same cops would be in the same neighborhoods every day, so that relationships would replace preconceptions, so that problem-solving and prevention would become tools officers were trained in and supported in using.

And, therefore, one of the great challenges of the policing profession, here in New York City and elsewhere, will always remain arresting someone who intends to resist that arrest. Communication and de-escalation techniques are employed where possible, but – more often than the police and the public, alike, would prefer – varying levels of force are used to ensure compliance. Society gives our police the legal authority to use acceptable levels of force, when necessary, because police cannot otherwise do their jobs.

Every day in New York, people receive summonses or are arrested by officers without any physical force being used. But some people choose to verbally and/or physically resist the enforcement action lawfully being taken against them. Those situations are unpredictable and dangerous to everyone involved. The street is never the right place to argue the appropriateness of an arrest. That is what our courts are for.

Being a police officer is one of the hardest jobs in the world. That is not a statement to elicit sympathy from those we serve; it is a fact. Cops have to make choices, sometimes very quickly, every single day. Some are split-second life-and-death choices. Oftentimes, they are choices that will be thoroughly, and repeatedly, examined by those with much more time to think about them than the police officer had. And those decisions are scrutinized and second-guessed, both fairly and unfairly.

No one believes that Officer Pantaleo got out of bed on July 17, 2014, thinking he would make choices and take actions – during an otherwise routine arrest – that would lead to another person’s death. But an officer’s choices and actions, even made under extreme pressure, matter.

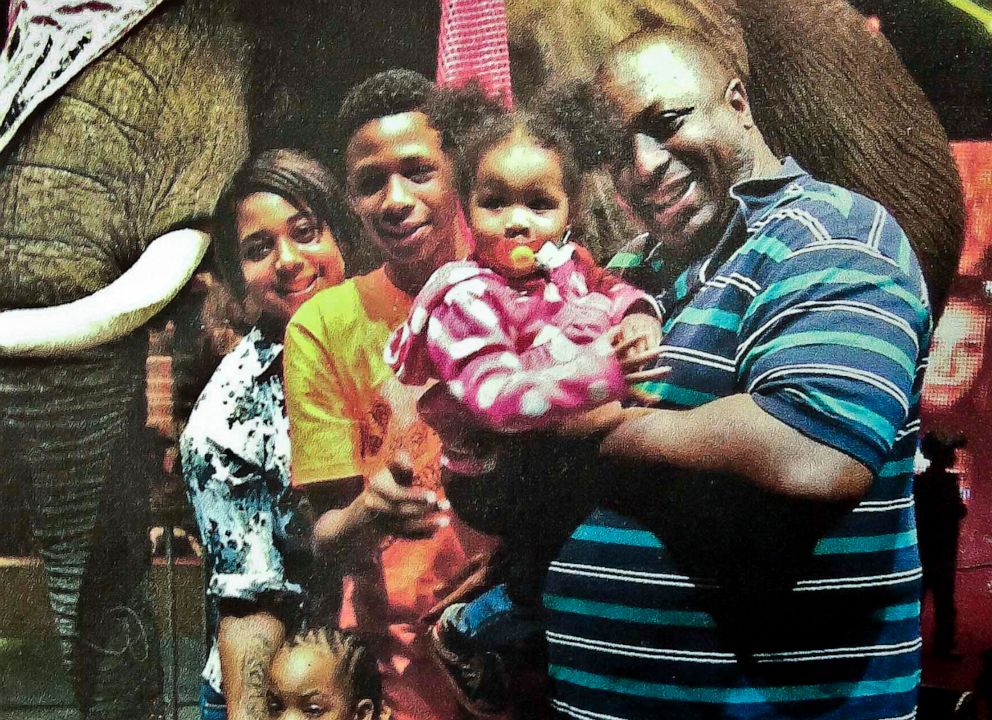

It is unlikely that Mr. Garner thought he was in such poor health that a brief struggle with police would cause his death. He should have decided against resisting arrest. But, a man with a family lost his life – and that is an irreversible tragedy. And a hardworking police officer with a family, a man who took this job to do good – to make a difference in his home community – has now lost his chosen career. And that is a different kind of tragedy.

In this case, the unintended consequence of Mr. Garner’s death must have a consequence of its own.

Therefore, I agree with the deputy commissioner of trials’ legal findings and recommendation. It is clear that Daniel Pantaleo can no longer effectively serve as a New York City police officer.

In carrying out the court’s verdict in this case, I take no pleasure. I know that many will disagree with this decision, and that is their right. There are absolutely no victors here today – not the Garner family, not the community at-large, and certainly not the courageous men and women of this police department, who put their own lives on the line every single day in service to the people of this great city.

Today is a day of reckoning but can also be a day of reconciliation.

We must move forward together as one city, determined to secure safety for all – safety for all New Yorkers and safety for every police officer working daily to protect all of us.