Who killed JonBenet Ramsey? An investigator's dying wish keeps the search going with his family

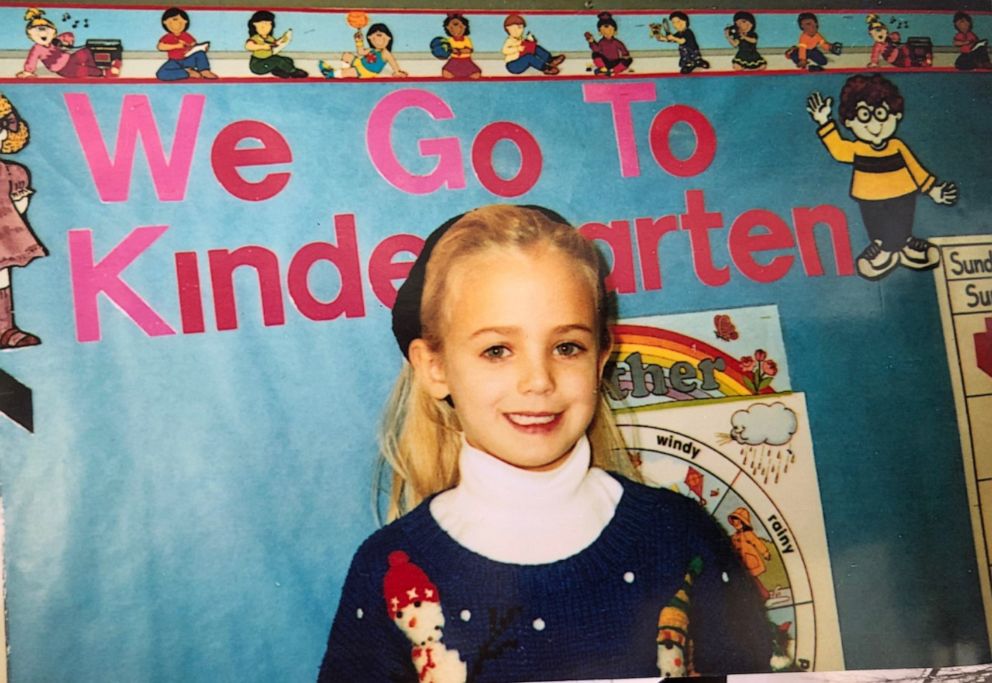

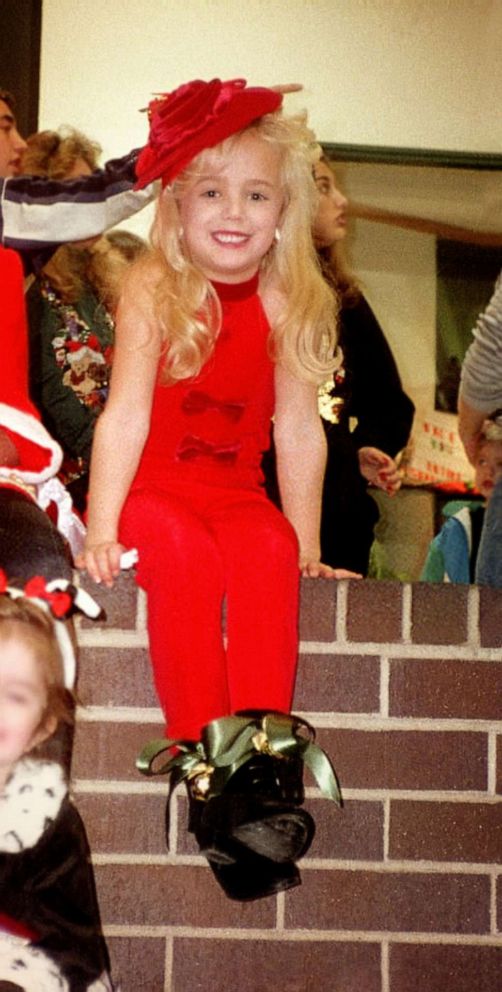

The 6-year-old girl was found dead on the morning after Christmas 1996.

Some people call Lou Smit a legend.

The Colorado detective who died from cancer in 2010 had investigated over 200 cases over the course of his career and every one of them had led to a conviction, according to his granddaughter Jessa van der Woerd. She is now tasked along with other members of Smit’s family with solving his last case as part of his dying wish -- that of 6-year-old JonBenét Ramsey.

Watch the full story on "20/20" Friday at 9 p.m. ET on ABC.

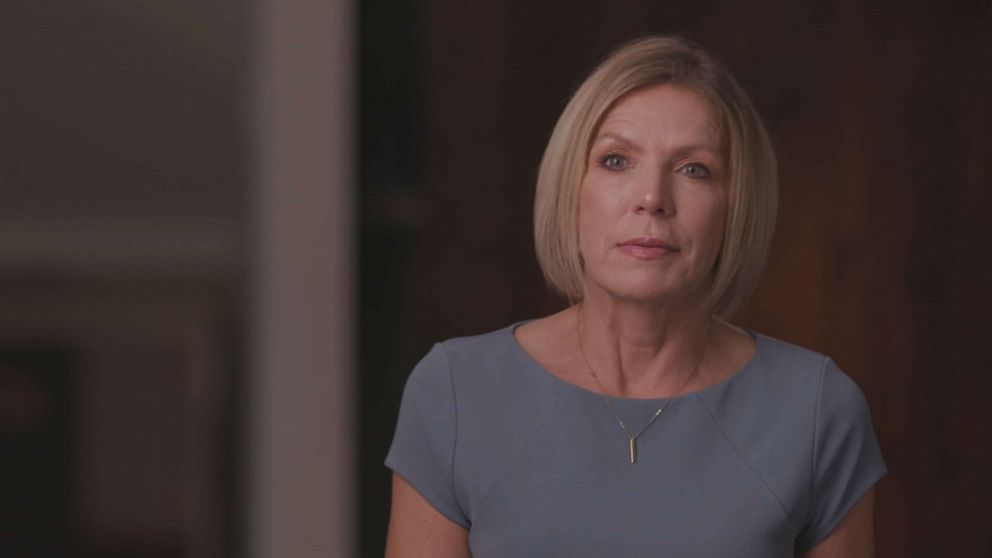

“When he got sick with cancer … he knew that his time was limited and so, during that time, he just talked to others about not letting this case die,” said Cindy Marra, Smit’s daughter. “It was really important to him.”

As part of their promise to keep the case alive, van der Woerd and Smit’s other granddaughter, Lexi Marra, created the podcast “The Victim’s Shoes,” where they discuss details of the case.

Smit was called out of retirement to help the investigation three months after JonBenét was found dead in the basement of her parent’s Boulder, Colorado, home on the morning of Dec. 26, 1996. The child beauty queen had died sometime during the previous night but wasn’t found until hours later.

JonBenét is found dead in her parents' basement

JonBenét’s parents initially thought she had been kidnapped during the night. In a 911 call just before 6 a.m., her mother Patsy Ramsey was inconsolable as she told the dispatcher that her daughter was missing and that she’d found a ransom note at the bottom of her stairs.

The three-page long note said in part that if JonBenét’s parents called the authorities, she would die, and asked for $118,000. It also said that JonBenét’s parents would receive a call from the supposed kidnapper “tomorrow” between 8 a.m. and 10 a.m.

“It was awful,” John Ramsey told ABC News’ Barbara Walters in 2000. “First of all, we didn’t know whether the kidnapper was going to call that day because the note said, ‘I will call you tomorrow. Get plenty of rest.’ I was deathly afraid that tomorrow was, in fact, the 27th.”

“You lose all perception of time, of place,” added Patsy Ramsey in 2000. “You’ve just been dealt a horrible, crushing blow.”

Police arrived shortly after the 911 call and began investigating the scene for clues about the kidnapper. However, with the Ramseys’ friends showing up for moral support, they also contaminated the scene by moving about the house.

“The police did a terrible, terrible job securing that scene … and if you don’t secure the scene, you don’t get good evidence,” said Diane Dimond, an investigative reporter who covered the case. “People were streaming through that house. They were in the kitchen, they were in the living room. There were some friends of Patsy’s that were helping her wipe up the kitchen. There could’ve been fingerprints there.”

After several hours, the police began to leave the Ramsey home. JonBenét’s parents anxiously waited for the supposed kidnapper’s call with just one detective there: Linda Arndt.

But when 10 a.m. passed and there still wasn’t a call, Arndt said “there was no acknowledgment” from either of JonBenét’s parents that “the deadline imposed by the author of the ransom note [had] come and gone.”

Arndt suggested that John Ramsey look around the house for any signs that his daughter’s belongings were out of place. He found JonBenét in the basement, a part of the home that police had neglected to search.

“I knew instantly what I found. I found my daughter,” John Ramsey told Walters in 2000. “She was lying on a white blanket. The blanket was wrapped around her. Her hands were tied above her head. She had tape over her mouth. … I immediately knelt down over her, felt her cheek, took the tape off immediately off her mouth. I tried to untie the cord that was around her arms and I couldn’t get the knot untied.”

John Ramsey said he brought his daughter upstairs and laid her on the floor, hoping she was alive. Arndt confirmed to him that the child had died.

Arndt said the moment sparked fear in her that JonBenét’s father might have killed their daughter, and so she braced herself for a possible confrontation.

“As we looked at each other, I remember -- and I wore a shoulder holster -- tucking my gun right next to me and consciously counting [that] I’ve got 18 bullets,” Arndt said, adding, “I didn’t know if we’d all be alive when people showed up.”

JonBenét’s cause of death was determined to be strangulation with a makeshift garrote, a weapon that, in this case, involved a string wrapped around a piece of one of Patsy Ramsey’s paintbrushes. The child had also suffered an 8-inch skull fracture, shocks from a stun gun and sexual abuse with a broken piece from the paintbrush used in the garrote, according to Brad Garrett, a former FBI agent and ABC News contributor who wasn’t involved in JonBenét’s case.

JonBenét’s murder came on the heels of the O.J. Simson trial and quickly gained traction with news outlets around the world. With the case now in the public’s view, police sought to question JonBenét’s parents.

“Particularly when you start with children of this age, when they die, tend to die at the hands of their parents,” Garrett told “20/20.” “So the focus is naturally gonna be on the parents to begin with. Now, in the house, the ransom note is written on a pad that belongs to Patsy.”

He said police began to suspect that maybe the Ramseys had “harmed their child in some way, then panicked and tried to create basically a kidnapping scenario.”

There were some reasons to suspect this. The three-page ransom note, for example, was written on Patsy Ramsey’s notepad with a pen that had come from the house. The $118,000 figure also seemed suspicious to authorities.

“You think about this number and how it’s relevant… John Ramsey got a bonus from his company for $118,000,” Garrett said, referring to JonBenét’s father. “How many people knew that? I’m gonna guess not a lot of people,” Garrett said.

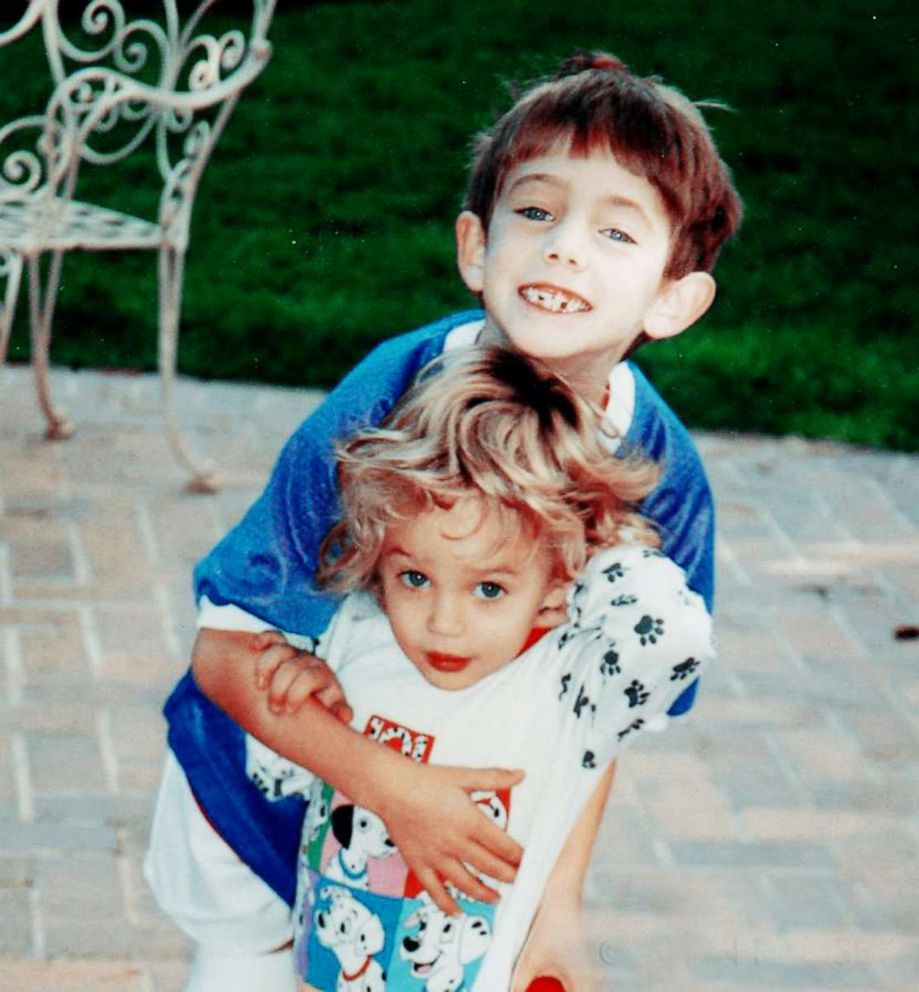

John Ramsey’s son, JonBenét’s half-brother John Andrew Ramsey, said that the family gave blood and fingerprints to the police as part of their investigation. But speaking to JonBenét’s parents, the main suspects in the case at that point, as part of a formal interrogation at the police station was challenging.

“The police … are faced with lawyers and wealthy friends. People in the community who tell the police, ‘Give them room. They’re grieving. What’s the matter with you,’” said Dimond. “The police are thinking, we gotta talk to those parents and we gotta talk to them right now before they start getting their story straight together.”

John Ramsey said they had asked police to meet them at their home because Patsy Ramsey was sick with grief in bed, “barely able to move.”

“We were perfectly willing and anxious to speak with the police to find the killer,” he told Walters in 2000. “We had a higher priority at that point and that was to bury our daughter.”

JonBenét was buried in Marietta, Georgia, the Ramseys’ hometown, on Dec. 31, 1996. Then, the next day, her parents appeared on CNN for an interview in which they pleaded for the public to help them find their daughter’s killer.

Patsy Ramsey said that when they found out they were main suspects in their daughter’s death, she “didn’t believe it.”

“I mean, we’re suffering from having lost our child … and then, for someone to accuse you, it’s just, you can’t believe that would happen,” she told CNN in January 1997.

“We were outraged. We were shocked,” added John Ramsey. “How could they think that? We were a normal family.”

Lou Smit begins investigating JonBenét's murder

Despite their denials, police continued to suspect the parents in JonBenét’s murder. Boulder County District Attorney Alex Hunter, however, wasn't convinced of their guilt and wanted to explore other theories. Three months after JonBenét’s death, he brought Smit into the fold. He quickly began reviewing the evidence and finding potential leads that the police and public had overlooked or dismissed.

“It seemed as though the parents were probably involved,” Smit said in video diaries that he began recording while investigating the case. “I thought this was [going to] be a fairly easy case. I thought it would be a slam dunk, and I even remember talking to my daughter. I kind of joked with her, saying that, ‘If somebody did get in that house, it must’ve been Santa Claus coming down the chimney.’”

But as Smit began to investigate the case, he started to believe that police should actually be looking at a possible intruder. He pointed out the open window in the basement, but photographs showed cobwebs on the window that would’ve likely broken had someone snuck through.

Police didn’t believe it was possible to fit through the window, and then Smit showed them it was by going through it himself.

“The big question is could you have gotten through this window -- this small window -- without disturbing this cobweb,” Garrett said. “I think the answer to that is ‘maybe.’ … But the other important point is how soon was this picture taken after JonBenét was killed because spiders can replicate webs very fast.”

Police had also found a shoe print from a Hi-Tec brand boot near JonBenét’s body -- no one in the family-owned shoes from this brand -- as well as two marks on her face and back, which he deduced had been made by a stun gun.

“There’s no reason at all for the Ramseys to use a stun gun and the Ramseys don’t have a stun gun,” Smit recorded himself saying at the time. “If it’s not a stun gun, what is it? That’s the question I always ask.”

In his video diaries, Smit pointed out that whoever wrote the ransom note included language that was drawn from several movies. Specifically, he noted the similarities to the kidnap drama “Ransom,” which had been playing in Boulder at the time.

“In that particular movie, a ‘fat cat’ industrialist, his son was kidnapped. There’s a lot of the same verbiage in this note as was in even the note that was written in that particular movie,” Smit said in the recordings.

The note said, “You are not the only fat cat around,” and also included other lines that were similar to the dialogue from the films “Dirty Harry” and “Speed.”

Smit also spoke about the DNA evidence that police had found underneath JonBenét’s fingernails and in her underwear in the video diaries. He said that this evidence “was not something that was made public for quite a long time.” An analysis found that it didn’t match anyone in the Ramsey family.

After JonBenét’s parents’ first formal interrogation in the spring of 1997, four months after her death, it would take nearly two years for them to sit down with the police for another interrogation. They returned for another one in June 1998, but this time, the investigators recorded it on video.

“There were months and months of negotiations, things about whether they could be videotaped, what are the questions going to be … should the Boulder police be a part of it,” said Carol McKinley, an investigative journalist. “The Ramsey’s said, ‘We don’t trust the police. We don’t want them there.”

The interrogation ultimately took place at a different police department and the Boulder investigators were forced to watch from a separate building. Tom Haney, a detective with the Denver Police Department, interrogated Patsy Ramsey, while Smit interrogated John Ramsey. Throughout both interrogations, JonBenét’s parents vehemently denied anyone in their family killed their daughter.

When Haney suggested there might be trace evidence that appears to link Patsy Ramsey to her daughter’s murder, Patsy Ramsey said, “That is totally impossible. Go retest.” He said she told him it was impossible for them to have “physical evidence” linking her to the crime.

Investigators weren’t able to find anything incriminating during the Ramseys’ interrogations. Smit’s daughter, Cindy Marra, said the interviews “firmed up his belief that the Ramseys had nothing to do” with JonBenét’s murder.

“I’m not saying parents don’t kill their kids … parents do kill their children,” Smit said in his tapes. “But [the police] are trying to say Patsy did it. … Their actions before, during and after [JonBenét’s death] are all consistent with innocent people. … They didn’t do it.”

As the investigation continued under Smit, he became concerned that authorities had totally ruled out the possibility of an intruder killing Jon Benet, and therefore weren’t looking for evidence of the possibility, Marra said.

“I thought there was something drastically wrong and that there was a gross injustice in this case,” he said in the tapes. “I had seen evidence of an intruder in the house that night.”

With his intruder theory regarding JonBenét’s murder increasingly pushed by the wayside, Smit ultimately chose to resign from the case, writing in a letter to Boulder District Attorney Hunter: “Even though I want to continue to participate in the official investigation and assist in finding the killer of JonBenet, I find that I cannot in good conscience be a part of the persecution of innocent people,” said Smit, referring to JonBenét’s parents. “It would be highly improper and unethical for me to stay when I so strongly believe this.”

But even as he stepped away from his official role in the case, he continued to push for justice for JonBenét while standing on her parents’ side, Marra said.

When Hunter called for a grand jury to assess the evidence in 1998, two years after JonBenét was killed, they listened to Smit’s intruder theory. But like police, the jury didn’t believe someone could’ve entered the window with the cobwebs remaining intact.

Jonathan Webb, one of the grand jurors, told “20/20” that Smit’s intruder theory didn’t make sense. For someone to get through a small window like that and not disturb the cobwebs “would be remarkable,” he said.

The grand jury ended up accusing both John and Patsy Ramsey of “unlawfully, knowingly, recklessly and feloniously permitting a child to be unreasonably placed in a situation which posed a threat of injury to the child’s life or health” as well as “rendering assistance to a person, with intent to hinder, delay or prevent the discovery, detention, apprehension, prosecution, convictions and punishment of such person for the commission of a crime.”

But although the grand jury may have believed one of the parents was culpable and the other helped, they couldn't say who did what, and Hunter ultimately announced that they did not have sufficient evidence to file charges against the parents.

In the ensuing years, Smit continued to look at the information he had on the JonBenét case and compiled it all into a database. He believed the answer to the identity of JonBenét’s killer lay in the DNA found in her underwear and underneath her fingernails.

By 2008, new DNA testing technology had been developed, called touch DNA, which allowed forensic experts to test the dead skin cells left behind on objects at crime scenes. Mary Lacy, the district attorney of Boulder at the time, decided to use this new test on JonBenét’s pajama leggings and the results came back positive for at least one unknown male’s DNA, possibly even two.

It was after this test that Lacy wrote a letter to John Ramsey stating that her office does not consider him, his wife Patsy Ramsey or anyone in their immediate family to be under suspicion for the death of JonBenét.

Patsy Ramsey died of ovarian cancer in 2006 and was buried next to JonBenét in Georgia, JonBenét’s half-brother, John Andrew Ramsey, said.

Lou Smit Dies, but the search continues

After 13 years, Smit still believed that an unidentified intruder was responsible for JonBenet’s murder. But he was running out of time.

He was diagnosed with colon cancer in 2010. But even as dozens of people visited him each day to pay their respects at the hospital, and later in hospice, he never stopped talking about JonBenét’s case, according to his other daughter, Dawn Miller.

Marra said that before his death, while he was still in the hospital, he told her that he wanted someone to keep investigating the case.

“He just said, ‘I want somebody to continue this case. Please don’t let it die,’” she said. “And he asked me to write down a name, and I did. I got a pen and paper and he gave me a name, and he said, ‘Start with this name.’”

Smit died on Aug. 11, 2010.

Marra said that after his death, her family teamed up with some of Smit’s former homicide partners to keep investigating the case.

“What we all share in common is that commitment to fulfill Lou’s dying wish that this case doesn’t die with him,” said John Anderson, a friend of Smit’s and former sheriff of El Paso County in Texas. “I think it’s that devotion, that respect, that love for Lou, [that] is what keeps our team moving forward.”

The team referred to the database Smit had created to begin narrowing down suspects. Among the names on the list were Gary Oliva, a homeless man who frequented a church less than two blocks from the Ramsey home and who had told a friend during a phone call right after JonBenét was killed that he had just killed a little girl, McKinley said.

Authorities ultimately cleared Oliva as a suspect after they were unable to connect him to the crime scene.

Bill McReynolds, a man who dressed up as Santa Claus for Christmas parties at the Ramseys’ home for three years, was also investigated but ultimately cleared when his DNA did not match that found by investigators.

Michael Helgoth, who owned a pair of Hi-Tec boots and a stun gun and had died by suicide shortly after JonBenét’s murder, was also cleared after the team found his DNA did not match that found at the crime scene.

“We went through the people of interest ... and came up with our top 20. Now, out of that top 20, what our team has been doing is focusing on collecting DNA and testing DNA,” Anderson said. “We’re not investigators. We’re not interrogating possible suspects. Any information that we come up with a match will be turned over immediately to the Boulder [district attorney] and Boulder Police Department, and they will follow that.”

“We are just trying to eliminate people from that list and we just figure, if we keep at it, hopefully, we’ll finally whittle it down to one person remaining on that list,” said Marra.

Anderson said that the team narrowing down Smit’s list met with Boulder authorities in September 2020 to present the list of their top 20 suspects in the case. Marra said she doesn’t believe “at this point that they are actively investigating this case.”

When reached for comment, the Boulder Police Department said there is still an active, ongoing investigation into JonBenét’s murder; however, the department has never publicly commented on its handling of the case.

Marra believes her daughters, Smit’s granddaughters, will push forward his dying wish even if they’re unable to.

“My daughters … will continue on with this case when we end up being too old to do it,” said Marra. “But we’re not gonna stop investigating. We’re just not going to do it.”

In the aftermath of their daughter’s murder, John Ramsey went on to lose his job and claims he spent millions of dollars on private investigators, lawyers and security.

While JonBenét’s half-brother, John Andrew Ramsey, said his father has remarried and is focusing on life, he also said their fight for justice on behalf of his half-sister is not over.

“The family has not lost the will to fight and the will … to find the killer,” John Andrew Ramsey said. “We work on this daily. There’s a group of dedicated volunteers that work on this daily.”

“I think it’s really important for people to understand that this case can be solved,” he went on to say. “There’s a narrative out there that this is an unsolved homicide and that we just have to accept that as a fact, and that is not the truth. If we leverage the evidence, we follow the facts, we will find this killer.”