How the small ski town of Sun Valley, Idaho became a COVID-19 hot spot

Over 100 people from a ski summit tested positive for the virus

In early March, the ski town of Sun Valley, Idaho, was ending its peak season, welcoming visitors from across the United States and Europe. Then COVID-19 spread across the community like wildfire, and Sun Valley's visitors brought it home with them. Within weeks, the county of 22,000 had one of the highest infection rates in the nation.

At first, the local hospital was hearing reports of some townspeople losing taste and smell -- but the skiers still arriving had no idea.

Watch the full story on "Our New Reality": A Diane Sawyer Special TONIGHT at 9 p.m. ET on ABC. Scroll down to take part in her re-entry quiz.

Debbie Bacca, 53, a local project manager at a construction company said COVID-19 wasn't a worry at the time.

"It still really wasn't talked about much here. I think Seattle had just started to blow up," she told ABC News. "Everybody thought, you know, we thought we were isolated enough to be immune. Which is exactly the opposite, as we have so many people coming in and out of town."

On March 6, Bacca went with friends to an after-ski party, she remembered the entire lodge was packed with hundreds of revelers.

"There were people up on the bars, the credenzas, chairs, tables," she said. "The six of us were sort of in a further part of the lodge, we probably most away from the dance floor. And we were just sort of sitting around drinking margaritas and taking it all in."

"It was just... it was crazy and it was fun and I'm sure it was just germ heaven," she said. "We grab and sit down at the table and one of us said, 'Maybe we should wipe it down.' But it was mayhem and it was, it probably wasn't a realistic idea," Bacca remembered.

Three days later, she was exhibiting symptoms. Five of the six in their group were infected with COVID-19.

"I had one sneeze and it was one of those sneezes where you were like, 'Oh, something's coming,'" Bacca said. "Then the next morning I couldn't get out of bed. Every single part of my body hurt."

She was the first official case of COVID-19 in the county, according to the Idaho Department of Health and Welfare.

Her friend Jody Zarkos had also been at the party. Zarkos, her husband and daughter also got sick.

"After 10 days we could count 30 people, 40 people, 45 people in our immediate network" who were also infected, Zarkos said.

"When I was getting tested, I talked to one of the nurses about my friend being the first person with coronavirus, and she shook her head and said, 'That's absolutely wrong. We've been seeing a mysterious respiratory illness for the past six weeks.'"

Among the visitors to Sun Valley that first week of March were the National Brotherhood of Skiers, a summit of the best African American ski clubs across the country. Founded in 1972, they meet annually to bring black skiers and snowboarders together. Their mission is to get a black member on the Olympic team.

After a week of skiing and events, the National Brotherhood of Skiers flew home from Sun Valley to airports across the country. Then, many of them began to feel sick -- reporting fevers and struggling to breathe. Some raced to ER departments across the country.

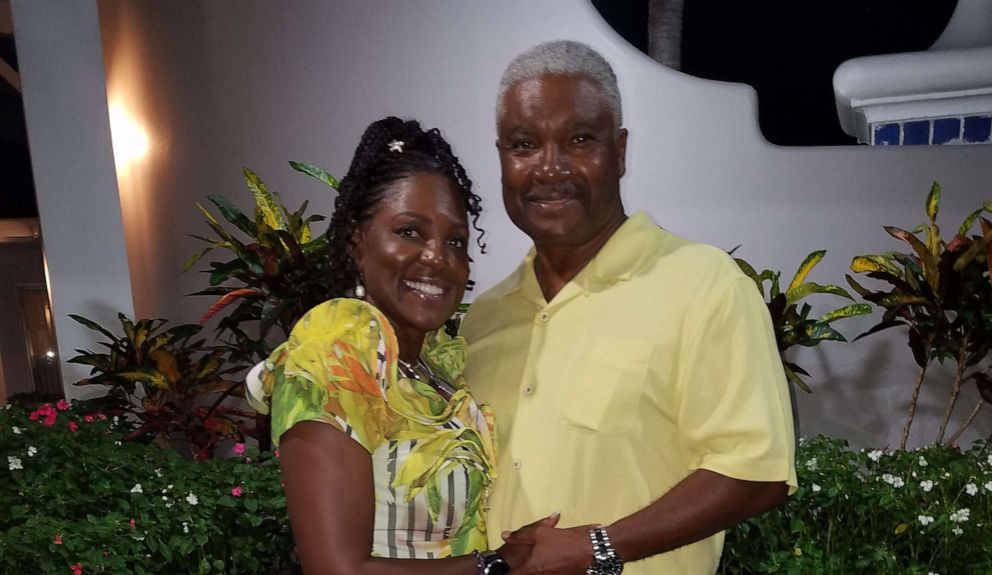

Mark Toliver, a retired FedEx IT specialist, and his wife, Stephanie Harris, a wellness advocate, flew home to Pompano Beach, Florida.

At first, she just thought he was tired and suffering from jet lag. Then he got worse.

"I thought it may have been the flu… it's just I never felt that sick in all my life," Toliver told ABC News.

So Harris called urgent care.

"They immediately said, 'We have no COVID tests and we can't help you -- click,'" Harris recalled. "So I called primary care. And they said, 'Well, we don't have any COVID tests. So if he starts to get really ill, I would call 911.' So then I called the ER. They basically just told me, 'Well, you better call the health department.' Everything was just like, 'We can't help you.'"

At the hospital, she put to work her advocacy skills on behalf of her husband.

"I advocated... short of screaming and yelling," she said. "I said, 'We're not leaving until it gets tested.' I knew in my gut, I knew he had COVID-19 -- I just knew it… it was so extreme, he was so ill."

He tested positive. Luckily, Harris never got sick despite having been exposed to the same environment and having had physical contact with her husband.

"When I had the conversation with the epidemiologist after I told her where I had been, and she confirmed that she felt that it was most likely Sun Valley, and by that point we had been getting reports that people were ill, and some had tested positive," Harris said.

She said she immediately shared where she had been and who had come to her home so they could take the proper precautions.

Some of the people who attended the summit “were tested, some were not,” she said. “Some of them just thought it was a bug that they picked up. A lot of people did get sick. All the epidemiologist could offer was, you're in large groups gathering repeatedly throughout the course of the week. There's no question that this occurred in Sun Valley. So that's pretty much all we know."

Out of 600 brotherhood skiers,126 eventually got sick, and at least four lost their lives.

Back in Sun Valley, COVID-19 was tearing through the small community's hospital. Brent Russell, an emergency room doctor there, shared his story.

"Well it's hard to know for sure, but the last week in February, Seattle is out of school... most of our skiers at that time during that time were from Seattle and Seattle was a hotspot at that point. And so I suspect that the illness arrived more or less into the town around then," he said. "And then the following week, it really sort of exploded because we had a lot going on."

Because the virus hit so early, the community didn't realize how serious the outbreak was, Russell said.

"People were slow to accept that and to realize how bad it was, and so I got sick," he said. "There's still groups of people talking and groups of people not social distancing… they don't realize how bad this is."

"We didn't have enough people to keep going," he said. "There's seven full time emergency room doctors and five had been out."

As their hospital was buckling under the weight of the virus, the people of Sun Valley came together to back their health care workers. Caleb Morgan, a local film student, was inspired by their appreciation and is now working on a documentary about the community's nightly show of support.

"I heard outside a lady just screaming -- and I took a few moments to realize that the entire valley was doing it, howling," Morgan said. "I realized that it was actually in support of the healthcare workers."

A wolf cry echoing around the Rocky Mountains: support for medical workers, and for each other.

"People are coming out on their front doorsteps with drums, and fireworks and air horns. Some people are on their roofs. And it makes for an awesome shot, but it's also really powerful," he said. "These people [are] waving and having a good time in the face of uncertainty."

We all know the terrible toll that COVID can take. We also know that the country can’t stay locked down forever – and that states are loosening quarantines.We’ve designed a kind of quiz – it’s just for fun - that asks the question: What’s your re-entry personality? Take the quiz, and at the end you can see what you think, and find out what pollsters say.