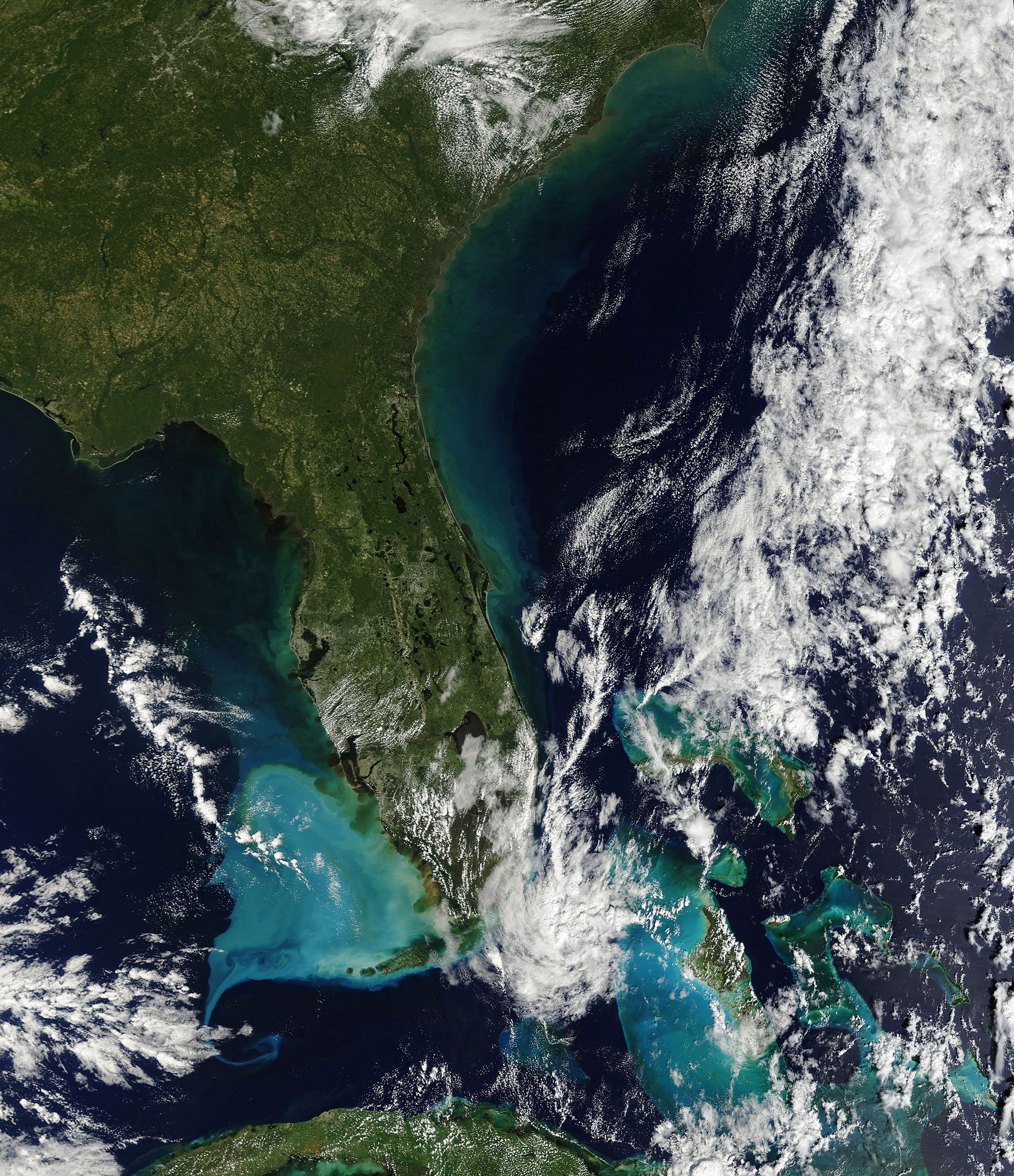

US Atlantic Coast becoming 'breeding ground' for rapidly intensifying hurricanes due to climate change, scientists say

Researchers are finding more evidence that climate change is to blame.

The East Coast of the U.S. will need to brace for more devastating storms like hurricanes Fiona and Ian should the global reliance on fossil fuels remain business as usual, scientists are warning.

Warming temperatures around the world are the root contributor that will cause more storm systems to behave like Fiona and Ian, with increased moisture and the likelihood of rapid intensification as they head toward land, according to a study published in Geophysical Research Letters on Monday.

This will make the Atlantic Coast of the U.S. a "breeding ground" for rapidly intensifying hurricanes, the researchers said.

Scientists at the Department of Energy's Pacific Northwest National Laboratory studied data over the past four decades of hurricane activity and the conditions that shaped them and found that the rates at which hurricanes strengthen near the U.S. Atlantic Coasthave significantly climbed since 1979.

The direct observations made by the researchers showed that the increase was "very likely due to climate change," Karthik Balaguru, a climate scientist at the Pacific Northwest National Laboratory and author of the study, told ABC News.

The trend will likely continue if the current level of greenhouse gas emissions continues around the world, according to the study.

A mix of environmental conditions caused by a unique phenomenon along the Atlantic Coast makes it more conducive to hurricane development, Balaguru said.

Land is already generally warmer than ocean waters. Still, as greenhouse gases build and global temperatures rise, land is heating up much more rapidly, and the ocean and the difference in temperature between land and ocean continue to grow, Balaguru said. The increase in the temperature difference between the land and the sea can create stronger storms, he added.

"Unlike the ocean with unlimited water supply, there's much less water in soil," Ruby Leung, an atmospheric scientist at the Pacific Northwest National Laboratory, said in a statement. "That means the land can't evaporate as much as water, so it can't get rid of the extra heat trapped by greenhouse gases as quickly as the ocean."

The same mix of hurricane-favoring conditions doesn't appear in the Gulf of Mexico but could form in other regions, including those near the East Asian coastline and the northwest Arabian Sea, the researchers said.

Combined with warmer ocean waters and greater atmospheric humidity, these conditions allow the storm systems to jump multiple storm categories in a short amount of time, according to the study. And because of the speed of the strengthening, the storms can often elude meteorological predictions, even with modern-day technology, the researchers said.

Last month, Hurricane Fiona caused widespread destruction in Puerto Rico -- five years after Hurricane Maria wiped out much of the island's infrastructure. Just 10 days later, Hurricane Ian did the same to southwest Florida, completely decimating Sanibel Island and Fort Myers Beach with deadly storm surge and catastrophic winds. Both storm systems strengthened into powerful Category 4 hurricanes before landfall.

Damage from weather and climate disasters could exceed $100 billion by the time 2022 comes to a close, the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration announced last week.

A study published in Nature in January found that annual costs of flooding alone in the U.S. could climb by 26% to $40.6 billion by 2050 as a result of climate change.

ABC News' Stephanie Ebbs contributed to this report.