Wheelchair-stroller built by students for new parent with impaired mobility

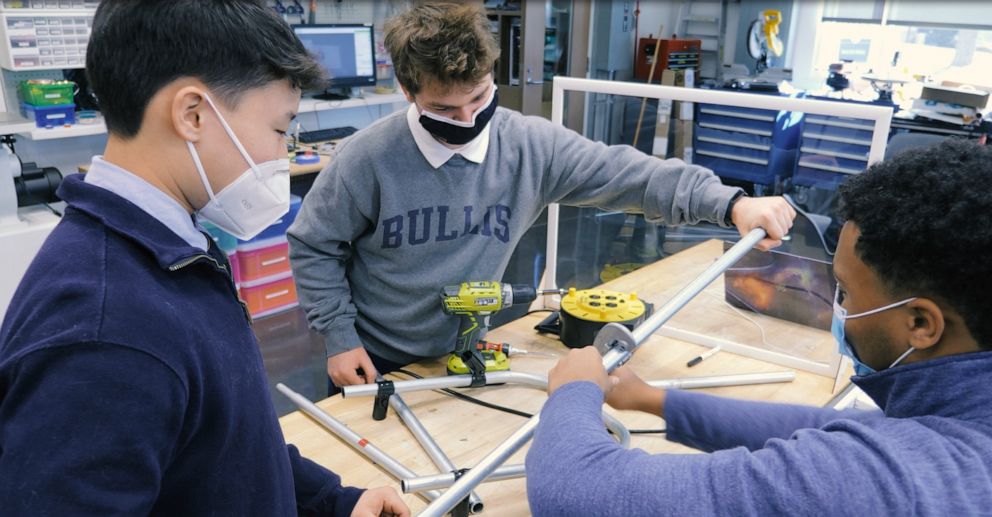

The invention was part of a class called "Making for Social Good."

A group of 10 high school students made it possible for a father with impaired mobility to walk with his newborn son.

Three years ago, Jeremy King, 37, from Germantown, Maryland, underwent surgery for a brain tumor that resulted in physical challenges like not being able to balance well. When he and his wife, Chelsie, 32, found out they were expecting in June 2020, the two were concerned about how they would take their child out on walks and other activities.

"While he can walk, he can't do so safely carrying a child," Chelsie King told "Good Morning America." "So we jumped into, 'OK, what do we need in order for him to parent safely?' and honestly, not a whole lot came up -- there's just really not a ton of resources out there for disabled parents."

Chelsie King turned to Matt Zigler, a teacher at Bullis School -- a K-12 school where King also works as a drama teacher and adviser -- for assistance. She asked Zigler if he could help them "come up with something that might attach to Jeremy's wheelchair."

At Bullis, Zigler teaches a high school class called "Making for Social Good," in which students design products that'll have a positive social impact. As the Kings' request lined up near the start of the trimester in November, Zigler told "GMA" he threw the challenge to his students to see what they could come up with.

"The idea of the course is to start out by trying to understand the problem, so we did interviews with the family," Zigler said. "We talked to somebody at the local fire department who actually does infant car seat installation training to try to better understand how those things work."

For Ibenka Espinoza, 17, who has known Chelsie King since eighth grade, the interview stages were some of her favorite because they all got to learn more about the Kings on a personal level.

"It was a good experience to have because we could ask them questions," Espinoza told "GMA." "I think that was the most fun."

According to one of the students in the class, Jacob Zlotnitsky, 18, it started with everyone having their own ideas for the wheelchair attachment and then 3D modeling what those would look like.

"We were all very goal-oriented," he told "GMA." "We were all focused on successfully making the best product we could in the amount of time we had."

They were able to narrow down the ideas to two projects which Zigler said "both address the issue in slightly different ways."

Afterward, the class was divided into two groups: one worked on the WheeStroll Stroller Attachment, which could connect an infant car seat to Jeremy King's wheelchair, and another worked on the WheeStroll Stroller Connector, which could connect an entire stroller to a wheelchair.

"Children grow and they grow out of a car seat so we wanted Mr. King to be able to walk with his son no matter what age he was," Zlotnitsky said.

The students used their school's MakerSpace to 3D print several parts and purchased others from Home Depot to build the attachments. They got a wheelchair from a school nurse to use as a model for things like weight testing.

"We were worried that it wouldn't be able to hold the baby because it might fall over or fall out of the attachment to the wheelchair," Evan Beach, 15, told "GMA." "So we tested it with cinder blocks to see if it would be able to hold a lot more weight than the baby."

Throughout the process, the students would frequently check in with the Kings to ask questions and get their opinions. For Jeremy King, their thorough research and dedication meant a lot.

"It was certainly emotional seeing the process and everything that went into this," he told "GMA." "I really feel the students took all my concerns to heart when creating the prototypes."

The goal, in addition to helping the Kings, was to create an affordable and accessible design that could be replicated at other MakerSpaces around the world so that other families with disabilities could benefit.

"With fairly cheap materials and tools, somebody that's a little bit handy could make these for someone," Zigler said, adding that instructions for how to build the attachments are available online.

The students finished constructing both designs in early March -- just in time for Chelsie King's March 4 due date. A few weeks after she gave birth to their son, Phoenix, she and her husband took the car seat attachment out for a spin.

"Using it was overwhelming because I never thought I would be able to do something like this with our son," Jeremy King said. "Most people can go out on a walk with their family but that is really difficult for me -- most people take that for granted."

While Chelsie King initially believed the inventions would be a personal favor Zigler helped her family with on the side, she's glad it became something much bigger.

"I love the idea that these students got this project and it'll be something long lasting," she said. "I know that they'll remember that for years to come, which is all you can hope for as an educator."

Beach initially took the elective course to see if he was interested in the subject matter and to make a difference in the community.

"Now seeing the difference that it's made, I think I'm pretty into engineering," he told "GMA." "It's amazing being able to see how they're really using it every day."

Due to his passion for engineering, Zlotnitsky said he gets attached to anything he makes but designing something that another person can actually use adds an extra layer of disbelief.

"I feel fortunate to have been able to take a class that has allowed me to truly make a difference in someone's life," he said.