In the 'epicenter of the epicenter,' were early heart attacks a missed coronavirus warning?

New data, reviewed by ABC News, shows virus followed cardiac arrest calls.

New York City officially earned the grim distinction of becoming the nation's coronavirus epicenter on March 20, but city records analyzed by ABC News suggest a crisis swelling far earlier, signaled by a sudden uptick in cardiac arrest cases that experts now say were likely linked to the virus.

Emergency calls for cardiac arrest began to climb in mid-February, in close-knit neighborhoods of Brooklyn and Queens, some of the same local areas that would soon form the "epicenter of the epicenter" of America's coronavirus pandemic.

"I've never seen anything like this," New York City Emergency Medical Services (EMS) Chief Lillian Bonsignore told ABC. "It was astounding. We went from normal to wartime EMS in a week. And then it was just explosive and it continued."

For nearly three weeks, she said, calls escalated exponentially, particularly cardiac arrest emergencies.

"We went from about 70 or 80 [cardiac arrests] a day which is what we normally do, to almost five times the amount," Bonsignore said. "I really was very surprised. I've never experienced a global pandemic."

Though early on other symptoms, like fever, were known to be warning signs of a coronavirus outbreak, doctors have since noted a strong link between coronavirus infections and heart damage, though exactly how the virus goes after the heart is unknown.

As the virus attacks a patient's respiratory system, other organs -- like the heart -- suffer stress, a complication that could lead to cardiac arrest and even death. The virus has also been found to cut the oxygen supply in some patients, something that could wreak havoc on the heart, especially among those who might already have cardiac problems.

"The most devastating" complication is "when the virus goes in and affects the heart cells directly and kills them," Dr. Varinder Singh, Chief of Cardiology at Lenox Hill Hospital on Manhattan's Upper East Side, said.

Tune into ABC at 1 p.m. ET and ABC News Live at 4 p.m. ET every weekday for special coverage of the novel coronavirus with the full ABC News team, including the latest news, context and analysis.

He said that the inflammatory response from the virus is so severe to the heart that there were reports of "seeing what looked like a classic heart attack." A majority of heart attacks are associated with clogged arteries, but Singh's team was surprised to find that in these patients "their arteries were actually normal."

Dr. Siyab Panhwar, cardiology fellow at Tulane Medical Center, also warned that it was "very possible" that blood clotting triggered by the coronavirus could be to blame and "causing more cardiac arrests."

As the coronavirus spread, Panhwar was brought in as a cardiology consult for COVID-19 patients and said he has seen the same patterns playing out as found around the world: an unexpected prevalence of blood clotting, sometimes followed by sudden events like cardiac arrest.

"It's a really interesting trend," Panhwar said. "Since autopsies aren't being done a lot right now, it's still hard to know. COVID-19 infections have a lot of effects on the heart, and just because we don't know everything yet doesn't mean it's not happening. It's worth looking at."

On Saturday night, medical examiners released the autopsy for what is now the first known coronavirus death in the nation: a woman in San Jose, in northern California's Silicon Valley. Patricia Dowd, 57, died in early February, from what appeared to be a massive heart attack, though she had also suffered flu-like symptoms.

She had coronavirus, which doctors did not know at the time. In addition to her heart, the virus had attacked her lungs and intestines, according to a medical examiner cited by the San Francisco Chronicle.

Back in New York, as COVID-19 jumped from person to person in densely populated precincts throughout the nation, New York City's biggest boroughs, Brooklyn and Queens, took the unwelcome status for most seriously overwhelmed. Front-line health care workers were seen triaging patients in tents, in hallways, in waiting areas -- any place they could.

By the time New York was declared ground zero for the American chapter in the pandemic, confirmed cases in the city amounted to a third of all cases in the U.S.

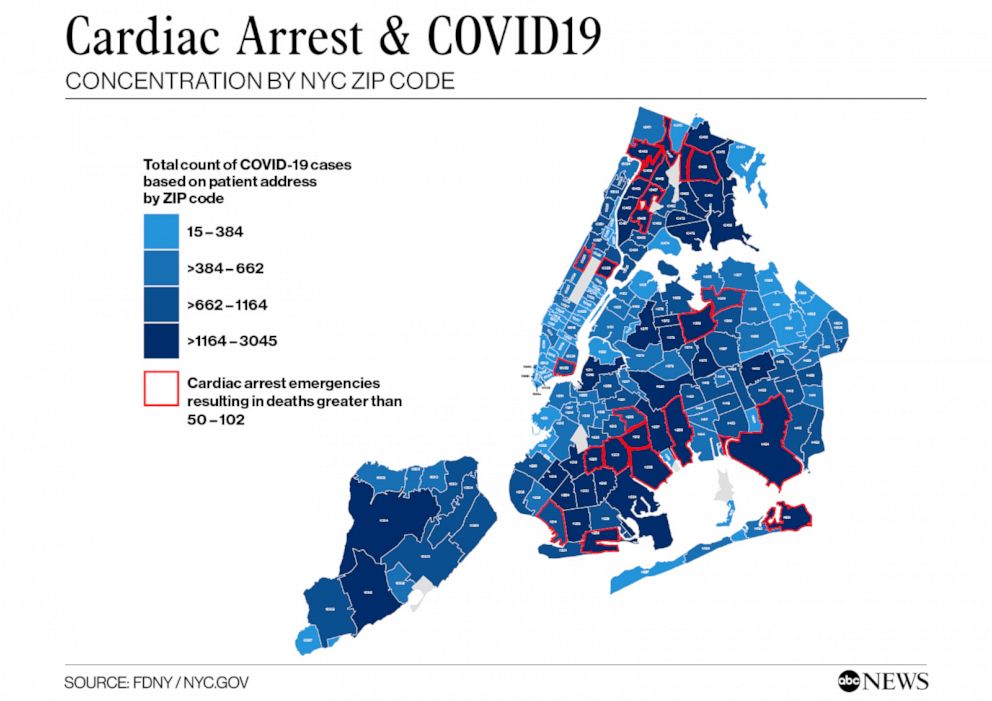

An analysis of EMS cardiac call data broken down by zip code reveals cardiac emergency calls and deaths both soaring with infection rates -- not just in tandem, but in the same neighborhoods. Looking back, it appears a significant portion of those heart emergencies were likely linked to the virus, according to medical experts consulted by ABC News.

"Significant hypoxia [from COVID-19] could be the root case of sudden cardiac death," Dr. Fred Jacobs, a pulmonologist and the former commissioner of health in New Jersey, told ABC News. Hypoxia is the medical term for the condition that occurs when too little oxygen reaches the body's organs, causing them to fail.

"The data is showing an increase in cardiac arrest calls in the areas that also show an increase in COVID-19. So the question will be, 'Is it causative?'" Jacobs said. "There are a lot of contributory factors here coming together in a perfect storm... This is a good part of the picture, but we also need a deeper dive into the data."

EMS call volume for cardiac arrests began rising to record levels at the end of March, the same time frame that saw hospitals like Elmhurst and Brookdale in Brooklyn bursting at the seams with coronavirus victims. By mid-April, numbers were more than six times what they'd been the same time a year earlier. On April 6, there were 366 cardiac calls; over 76 percent resulted in death. By April 13, the death rate had risen to more than 79 percent.

"This was new for all of us," Bonsignore said. "I really didn't know if we could do this - it happened so fast, like a tsunami coming in."

Areas of Jamaica, Corona and Far Rockaway in Queens; Brooklyn zones like Flatbush, East Flatbush, Brownsville, Canarsie and Bedford-Stuyvesant; in the Bronx, Kingsbridge and Allerton saw high volumes of cardiac arrest calls and deaths. They all were also struck with acute clusters of the virus, with the majority within the highest bracket of between 1,164 and 3,045 cases.

In the high-pressure push to learn more about what first responders have called a "silent bullet," experts say there is a critical need for medical science to know more about coronavirus.

To them, it's not just an academic exercise. Knowledge could make the difference between life and death when victims of COVID show up but present strange symptoms that could easily be mistaken, and it could help protect the front line workers responding as well.

"We have family members that are there, they expect a miracle, they expect we're going to bring back their loved one," Bonsignore said. "Our rescuers are resilient, they're dedicated to saving lives, but they're also human. And they themselves haven't been immune to this enemy. As we're doing this medical war on the front lines, our members were getting sick as well."

"I think we're going to have a lot of work to do when this is over," Bonsignore said. "This was new for all of us … I didn't know we could do it to be honest. This thing was spreading so quickly -- we're just working to stay in front of it."

What to know about coronavirus:

- How it started and how to protect yourself: Coronavirus explained

- What to do if you have symptoms: Coronavirus symptoms

- Tracking the spread in the U.S. and worldwide: Coronavirus map

ABC News' Josh Margolin contributed to this report.