Tracking the virus: 1 year of living with COVID-19 in the US

The first case in the U.S. was reported on Jan. 21, 2020.

This time last year, the United States was preparing for a possible pandemic, with nearly a dozen confirmed COVID-19 cases nationwide and cases in China topping 20,000.

Today, the U.S. has reported more than 26 million cases, accounting for about a quarter of all global cases, according to Johns Hopkins University,

It's a year that's been marked by tragic loss and economic strain due to the coronavirus pandemic, as well as historical scientific achievement forged on the path out of it.

COVID-19 quickly exposed challenges in the nation's pandemic response, experts say. There was mixed messaging and political tensions around masks, questions about the supply of protective equipment and ventilators and an emphasis on reopening the country economically in the spring over containing the virus.

"I think we missed the mark in several ways," Dr. John Brownstein, chief innovation officer at Boston Children’s Hospital and an ABC News contributor, said, pointing to slow testing and contact tracing efforts. "There was no sort of federal mandate to get this virus under control."

In response to criticism, the former Trump administration had said its decisions were "data-driven to save lives." Former President Donald Trump also touted vaccine production progress, saying in December, "I think that the vaccine was our goal."

As COVID-19 cases first began to mount back in March and April in the U.S., states scrambled to obtain personal protective equipment and medical supplies and implemented varied restrictions and health protocols, such as closing schools and mandating masks, to limit the virus' spread.

One of the regions hardest-hit first by the virus was New York City, where cases quickly surged in the spring, overwhelming hospitals to the breaking point.

"Everything was saturated," Dr. Matthew Bai, an emergency medicine physician with Mount Sinai, told ABC News. "The hospitals were saturated. Emotions were saturated. Everyone's work schedule was saturated. You had no time to breathe."

As many states began lifting restrictions in late spring, the U.S. marked a grim milestone on May 28 -- 100,000 COVID-19 deaths. Cases started to surge in regions that had largely avoided the initial wave, like Texas.

San Antonio resident Carlos Muniz was hospitalized with COVID-19 in July -- the month he was supposed to get married. He wouldn't leave until September, after marrying his bride from his hospital bed.

"Right after that wedding or that day, you know, it kind of clicked in me," he told ABC News. "It really did switch something in me like, Hey, look, I have to get through this. Right? And that next day, actually, I was able to sit up in the bed."

Muniz's story has a happy ending, though many haven't been so lucky. Throughout the fall and winter, COVID-19 cases, hospitalizations and deaths soared, breaking records as soon as they were set. More than 444,000 Americans have died from the virus as of Feb. 2.

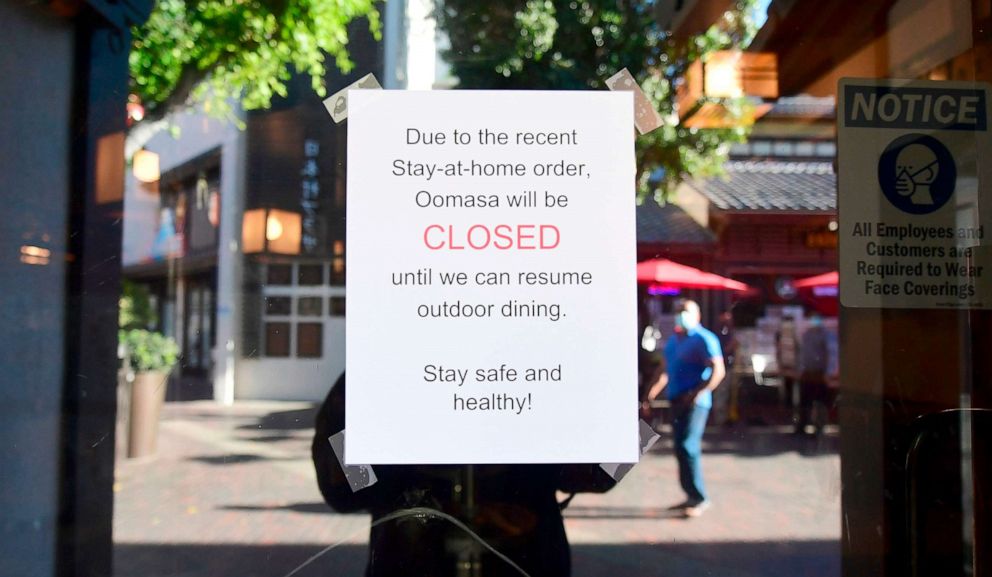

Unemployment claims have remained historically high throughout the pandemic, amid ongoing stay-at-home orders, although parts of the economy have begun to recover or -- in the case of big tech -- seen gains.

Restaurants -- which have been linked to the spread of the virus -- have been particularly impacted. By early December, more than 110,000 eateries and drinking establishments had closed during the pandemic, according to the National Restaurant Association.

The Golden State restaurant in Los Angeles held on throughout multiple stay-at-home orders and dining restrictions, before closing on Jan. 4.

"It was our intention to stay open as long as we could to keep people employed and also uplift our community because our food is very much, you know, kind of a beacon of the neighborhood. And I think people found comfort in knowing that we are still open and serving," co-owner James Starr told ABC News. "We were kind of just in this perpetual loop of just take-away and delivery without any other alternatives, really. So it was tough."

"We just ran out of money," he added.

As COVID-19 surged in the late fall and winter, there were signs of hope. Two vaccines -- one developed by Pfizer and the other by Moderna -- received emergency use authorization within a year of identifying the virus. The previous record for vaccine development was four years.

With one of the most ambitious vaccination deployments in history underway, new COVID-19 variants have been identified in the U.K., South Africa, Brazil and in the U.S. -- only emphasizing the need to immunize people as quickly as possible.

Some 32 million doses have been administered as of Feb. 1 -- a long way from the percentage of Americans needed for herd immunity. Achieving herd immunity by the fall in the U.S. is an "ambitious goal," Vivek Murthy, Biden's nominee for U.S. surgeon general, recently told ABC News chief anchor George Stephanopoulos on "This Week."

The past year has been unprecedented. But it should also serve as a "wake-up call," Brownstein said.

"This is not the last time that an emerging infectious disease will have an impact globally and in the U.S.," the doctor said. "We have to be vigilant both in the ways in which we identify new viruses and stop them at their source, but then also building better infrastructure within this country to respond."

What to know about the coronavirus:

- How it started and how to protect yourself: Coronavirus explained

- What to do if you have symptoms: Coronavirus symptoms

- Tracking the spread in the U.S. and worldwide: Coronavirus map

Tune into ABC at 1 p.m. ET and ABC News Live at 4 p.m. ET every weekday for special coverage of the novel coronavirus with the full ABC News team, including the latest news, context and analysis.