Elizabeth Warren gets taste of what it really means to be a front-runner

Despite strong poll showings, why do some voters think she can't beat Trump?

The spotlights at the fourth Democratic debate beamed down on the 12 candidates on stage, but Sen. Elizabeth Warren, D-Mass., faced an especially hot glare getting her first taste of what it really means to be a front-runner.

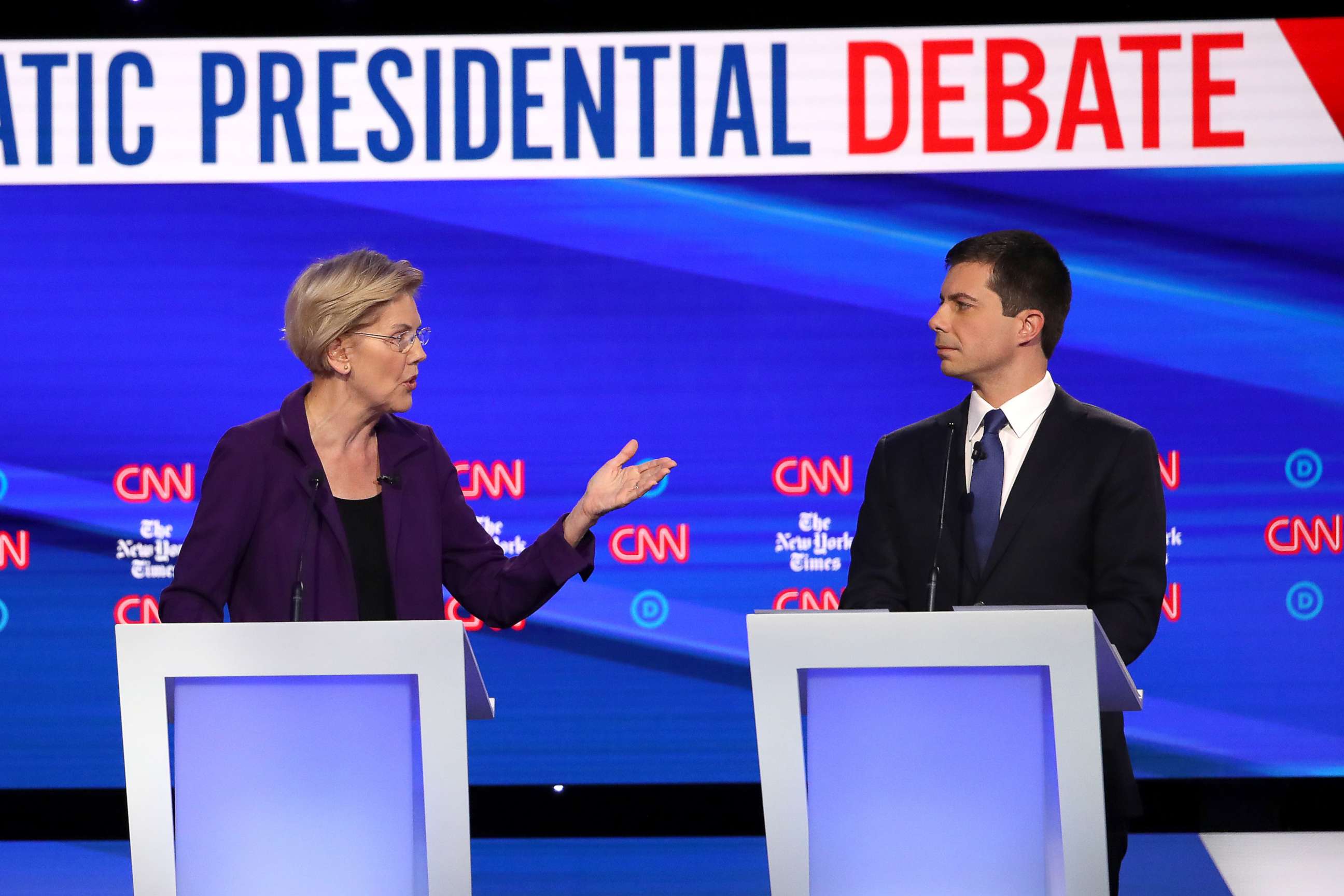

She faced sharp questions from the moderators -- and from rivals -- fending off attacks about how she would pay for "Medicare for All", her wealth tax and, generally, the infrastructure of her plan-heavy brand. Many of the remaining 2020 Democrats accused her of being "evasive" on some of the core points that buttress the narrative of her candidacy and her origin story.

Center stage and in her rivals' crosshairs, Warren met their salvos in turn.

And while the sometimes fiery exchanges highlighted salient questions about her policy prescriptions, experts noted, and polling indicates, a deeper undercurrent to the conversation -- and caveats to her ascendant star.

"We are accustomed to seeing a particular model of what it looks like to be a candidate for the presidency," Kelly Dittmar, a professor of political science at Rutgers University-Camden and scholar at the Center for American Women and Politics, told ABC News. "When it comes to perceptions of who is best to beat Donald Trump, voters make assumptions about who's won before."

She's got a plan for that

A former Republican, she's also a woman, as was the last Democratic nominee, former Secretary of state Hillary Clinton, the first woman nominated by a major party to top a ticket. Clinton won the popular vote vs. Trump but lost in the electoral college.

But Clinton espoused more centrist ideals than Warren's progressive platform. Moreover, this election cycle, Warren shares the primary ballot with other female candidates.

Still, Warren has surged in the polls, largely on voters' enthusiasm for her ethos and ideology.

An Oct. 2 national poll from Monmouth shows Warren leading the field +3 over Biden -- within the margin of error -- but shows their head-to-head matchup for the nomination tightening. In mid-September, Quinnipiac put Warren +2 over Biden; the same poll also showed that most Democrat and Democratic-leaning voters would be "excited" if she were to become the nominee -- at 70% -- where Biden was at 56%; Sanders, 55%.

"Warren has an idea and she knows how she's going to get there," Lauren Polkier of Providence, Rhode Island, told ABC after meeting Warren at a recent primary state convention, citing how relatable she finds the candidate's origin story.

"I think the biggest thing that inspires me is that she comes from this background very similar to mine -- tight-knit family, lower-middle class -- and she's beat the odds -- she's come up and she's made something for herself," Polkier said. "She's very charismatic, she has a clear and concise plan for every policy and every issue. ... She's very inspiring for me, and I want to see a woman in the White House, and I'm very excited to see that."

People often drive hundreds of miles across state lines for one of Warren's town halls, to see her, meet her, take a selfie with her. Warren's 70,000th selfie, according to the campaign, was a young mother with two little girls.

Melinda wore a bright red shirt that said, "Impolite arrogant women make history."

"She inspires us, she gives us hope for the future -- and we're here because of our girls," Melinda told ABC News.

Voters repeatedly say they're fueled by how she's a fighter, and they feel she'll fight for them, that she's not just a woman, she's a woman with a plan. But at Tuesday's fourth debate, as Warren's stock rose, her 2020 rivals took aim at those plans -- and at perceived gaps in them.

The fourth Democratic debate, at Otterbein University in Ohio, was the first time Warren faced other contenders after leading a major poll. That polling reflects her rise: She's neck and neck with former Vice President Joe Biden, even topping him in some.

And her onstage rivals didn't shy away from hammering Warren on her signature promises. She often talks about "having a plan for that" -- for everything -- but onstage, her rivals pilloried her for the lack of detail, especially when it came to her most expensive, most expansive plan, Medicare for All, which, ironically, isn't even hers and which Sen. Bernie Sanders, I-Vt., originated. Then, at times, she was accused of being in turns dishonest, punitive, naive and that she offered a "pipe dream" ethos of leadership.

Warren refused to say the word "taxes" when it came to paying for her version Medicare for All, as she's consistently avoided.

Yet in immediate post-debate polling, she did well, scoring high in her performance grade.

"Remember, a lot of Democrats come in liking Warren in the first place," FiveThirtyEight's Galen Druke noted in the wake of Tuesday's debate. Warren came in with high net-favorability rating. "And so Democrats come in kind of wanting to think the debate went well for Warren, so if it was kind of ambiguous, it might come out fine for her."

Voters like her energy, her enthusiasm, and how she links her personal history to her policy ideas.

High marks in most polls, so why don't voters think she can win?

Recent polling reflects people think she does have the "best" ideas -- by a wide margin.

Quinnipiac University's poll, released the day before the fourth debate, found that Democrat and Democratic-leaning voters expressed they think Warren has the best policy ideas by a wide margin: 40% of respondents giving her that nod compared with just 16% for Biden's ideas. However, those same voters said that when it comes to the imperative question of who has the best chance of beating Trump, Biden outpaced Warren by far, 48% to 21%.

When it comes to that crucial vote of confidence, Warren doesn't win. Why?

"The expectation of who is both capable and likely to lead in presidential office has historically been associated, not only just with men, but with white men," Dittmar said. "Candidates have had to do additional labor to push back against those expectations."

Voters cast ballots based on whoever seems most likely to win, based on the statistics from the last go-round, converging on a middle ground and sweetening the odds for a candidate on whom both sides can compromise.

"That's based on whether or not people assume other people have bias about who can and should lead and if they have certain perceptions of what other people will accept," Dittmar said.

Facing 'othering' as a female front-runner

Warren may also face an additional undercurrent of "othering" as a female front-runner.

However, the issue of perception of which candidates voters say they think their friends or neighbors will cast ballots for is not new to the 2020 primary.

In 2008, then-Sen. Barack Obama faced questions about his race that were coupled with concerns over his being a relative newcomer to Washington and his campaign's gamble on "hope" and "change."

Hillary Clinton, by contrast, was highly experienced but a hard sell to some as "electable" in her quest to shatter the "highest, hardest glass ceiling."

Even Donald Trump, a billionaire and proverbial Washington outsider, was not considered a politically serious option well into his campaign that promised to "Make America Great Again," a message targeting many of those hit hardest by the recent recession.

Democratic candidates will have to battle against the man who promised to drain the swamp; and this time, it's a historically diverse, progressive field: more women and minorities, with the largest age range in any presidential nomination race, challenging voters' notion of what's "electable."

Candidates now have to run two races: one to win votes, and concurrently, one to win belief. Those are two different matters and require a two-pronged approach -- when voters say they like you, but aren't sure enough people agree to make you unbeatable, Dittmar said.

And - winning that trust becomes tangled turf when gender comes into play and may be a sticking point.

'How she weathers attacks to come matters all the more now'

Questioning candidates' honesty is no novel territory, but it's an even bigger issue for women.

Warren's been scrutinized especially of late on several serious subjects, including discrepancies in her origin story told on the stump and whether she'd have to raise taxes to pay for her health care plan. Both are issues of her own making -- moreso the more she hedges -- and exacerbated as many Democrats seek a surefire winner over Trump.

"People have the belief and stereotype that women are supposed to be more honest -- well, then, when a woman gets caught in a lie, it's even more damaging," said Michelle Swers, a professor of American government at Georgetown University. "If they start on a virtue pedestal, people assume better of them. But then if they're knocked off that pedestal, the fall is longer and harder than it might be for men."

It's happened before: In 2016, when questions arose over Clinton's ethics and honesty, that's when the moniker "Crooked Hillary" stuck.

"Electability has often been interpreted through a gendered lens," Swers said, with women "usually needing to prove themselves even more qualified -- more credentialed."

When it comes to Warren, Swers added, that shows in spades: "The whole premise of 'I have a plan for that' is to show, 'I'm serious -- I'm not just making it up on the fly.'"

"Any candidate will have to go up against the clear discrepancy that women and people of color face, but this was the first time Warren really weathered any attacks and it was really quite fascinating," Democratic strategist Arshad Hasan said of Warren's latest debate performance. "You could see her get a bit impatient, but it was clear she was really conscientious that if she's seen as stern or angry, that would have an entirely different effect than for male candidates."

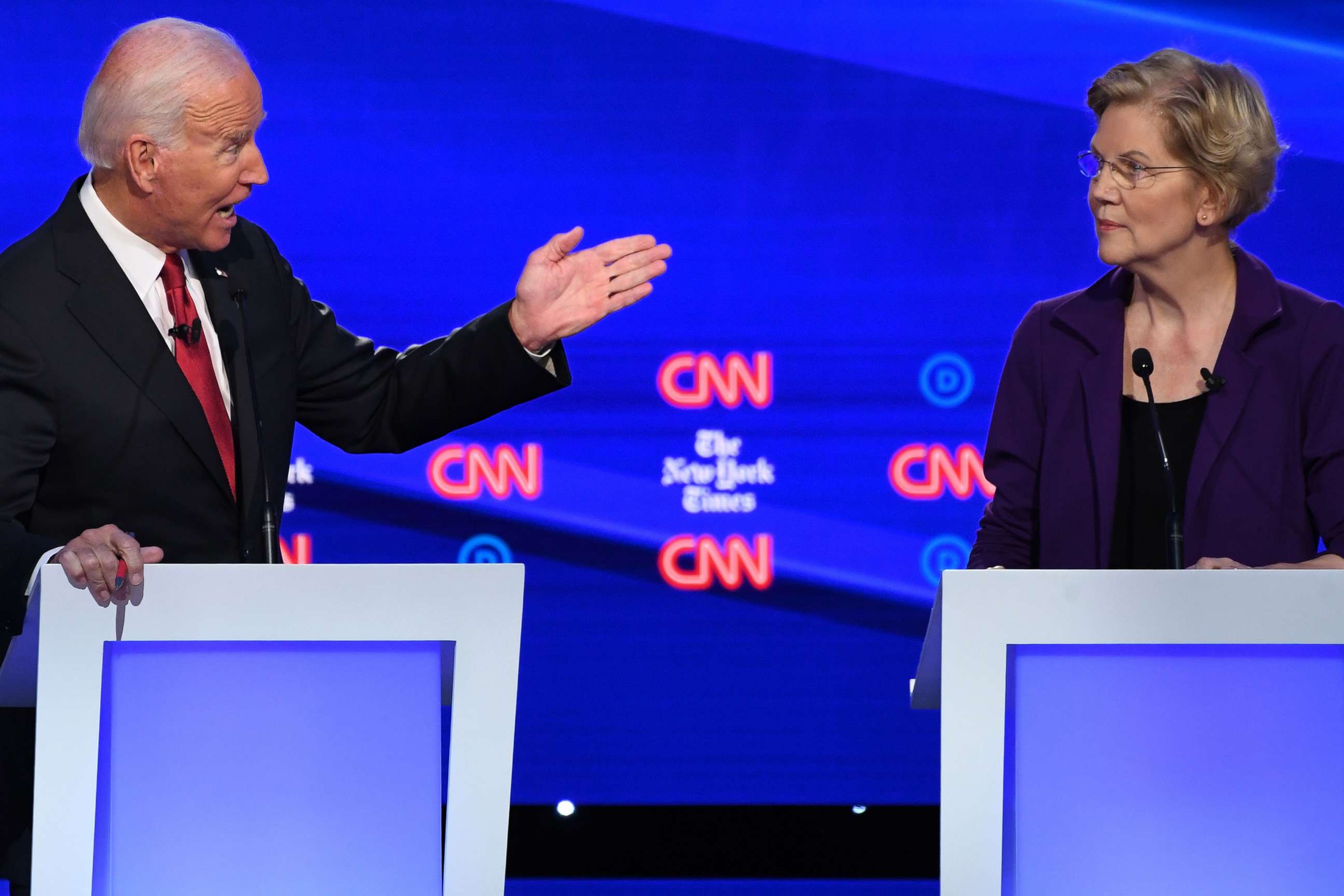

Warren weathered her rivals' wallops with composure, choosing her words very carefully. In a particularly prickly exchange with Biden over who deserves credit for the Consumer Financial Protection Bureau -- Warren's signature effort -- Biden grew visibly heated, gesturing widely into Warren's podium space.

"I agree with the great job she did, and I went on the [Senate] floor and got you votes!" Biden said, his tone rising. "I got votes for that bill. I convinced people to vote for it -- so let's get those things straight, too."

Warren stood stock still, letting him finish, and responded in a measured tone: "I am deeply grateful -- to President Obama, who fought so hard to make sure that agency was passed into law. And I am deeply grateful to every single person who fought for it, and who helped pass it into law."

In one move, she sought to cut Biden out of that page in history.

"There was Joe Biden, not only attempting to take credit for Elizabeth Warren's signature accomplishment, but then also to take her space. You don't have to be a body language expert -- any woman could see that Elizabeth Warren was being very considered in her reaction to Biden getting in her space and getting in her literal accomplishment," Hasan told ABC News.

"You saw her slow down and be very considerate about her words - she said, 'I. Am. Very grateful. For all the support -- that I got from Barack Obama," Hasan continued. "I mean, like, we all saw what she was doing -- the way that she said it, she was controlling herself and she was being so deliberate. It was a very clear, cutting comment to say, 'Do not -- do not! -- take my signature accomplishment, and take it over."

Any "attack" for female candidates -- taking it or giving it -- must be wielded as a finely tuned, finely sharpened weapon. "It's not as easy for you to just be purely angry, you have to be more strategic. Now, multiple female candidates on the stage show different elements of what is 'allowed,' and it's widening the circle of what's permissible behavior," Swers said.

When her opponents onstage, and even some pundits post-debate, grew visibly frustrated with some of her artful dodges, Warren stayed mostly tempered, even as she ducked the questions.

"Claire Mckaskill called her petulant," Dittmar said of the post-debate analysts. "You could say that about any of the candidates, but think about the effect when talking about a woman, who have historically been infantilized. So, will that cue play into existing negative stereotypes about women more easily?"

McCaskill, a former centrist democrat Missouri senator turned political analyst, knocked Warren for her tactics. But how will those affect voters' perceptions?

"Voters and viewers have certain expectations about dynamics between men and women -- about stereotypes of male dominance -- men have to worry about coming across as a bully," Dittmar said. "For Biden, he risks cuing some of those negative reactions, especially among women viewers, to see that sort of aggression and invasion of personal space as something that they themselves have experienced."

Warren played the moment to her advantage, Dittmar said, let the pauses be pregnant -- leaning back while Biden leaned in.

"She did that very well, she almost amplified his emotion, his aggression, by simply standing there very stoically. She played up the contrast in her body language and her tone," Dittmar added.

But friction between female candidates played out differently. Sen. Amy Klobuchar, D-Minn., called Warren explicitly by her first name.

"It's just the slightest slight," Hasan said, an index of familiarity, while still coming after Warren's policies sharply, that perhaps a male candidate couldn't have pulled off.

"We spend a lot of time thinking about how women engage on the trail, but it's equally as important to think about how gender functions for men," Dittmar added. In the wake of #MeToo "we've seen, and I think will see, men have to answer to this more than they have before."

The contrast of a woman onstage versus Trump this time, with so much happening since 2016, may yet prove advantageous for a well prepared female candidate.

"This is Warren's first day really at the top," Hasan said. "And I think this is going to play out a lot more: She's always been a woman, but she's never been a front-runner before… and the question now is where that room to grow goes."