With narrowed majority, Democrats on Hill face hurdles joining Biden Cabinet

By plucking Senators or House members, Biden could imperil his own agenda.

Congressional Democrats harboring dreams of joining President-elect Joe Biden’s administration are facing a math problem.

The party’s worse-than-expected performance in down-ballot races dimmed hopes of a Democratic-controlled Congress working with a Biden administration next year.

Facing a reality of divided government, Democratic leaders won't want to lose any votes to vacancies, special elections or gubernatorial appointments, according to congressional experts, lawmakers and operatives.

By plucking old Senate colleagues for his cabinet, or any number of House members to fill out his administration, Biden could be imperiling his own agenda -- and making every vote more challenging for his party in Congress.

“It's a legitimate concern,” former Sen. Mary Landrieu, D-La., told ABC News.

“President Biden needs to have his team around him in the White House, but he also needs a team with him on the House floor and the Senate floor,” she said. “You've got to leave your best players playing their best positions.”

Uphill climb for the Senate

While Democrats were favored to win the Senate majority and boasted of paths to gain at least four seats through competitive races in Maine, Iowa and North Carolina, strong turnout for Trump in those states left the party with only their expected pickups in Arizona and Colorado.

Now, Democrats are pinning their hopes for a majority on two runoff races in Georgia in early January — an uphill climb for a party that has struggled with special elections and now faces two in a state that has been firmly in GOP hands for decades until this presidential election. Even if they won, their majority would hinge on Vice President-elect Kamala Harris’ tie-breaking vote.

Barring any upsets in Georgia, Republicans are on track to control the chamber, which would force Biden to negotiate with Senate Majority Leader Mitch McConnell on every piece of his agenda -- from coronavirus relief and infrastructure, to executive and judicial nominations.

The likely uphill battle is not lost on Biden, who told supporters on a private call Wednesday that he’s likely to face “real brick walls” in the Senate if Democrats don’t succeed in Georgia, but stressed his fundamental belief that bipartisanship was possible.

“We're going to run into some real brick walls initially in the Senate, unless we’re able to turn around Georgia and pick up those two seats, but even then it's gonna be hard,” Biden said on the call.

“I believe — I know the place — I believe we can ultimately bring it together,” he continued.

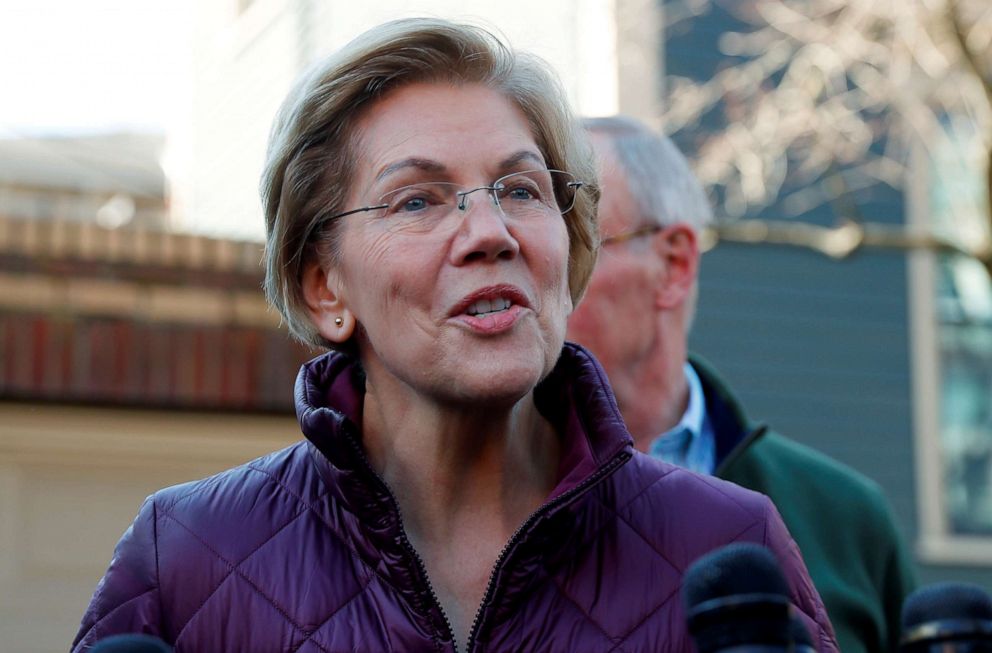

While each state has different rules governing Senate appointments and special elections, potential selection of Sens. Elizabeth Warren, D-Mass. or Bernie Sanders, I-Vt -- who are on progressives’ wish list for treasury and labor secretary, respectively -- would turn the fate of their Senate seats over to Republican governors, who could appoint members of their own party to replace the prominent Democrats in Congress. (Gov. Charlie Baker of Massachusetts (R) has pushed back against state Democrats’ efforts to force him to fill a Senate seat with a member of the same party, while Gov. Phil Scott of Vermont (R) has only said that he would fill a Sanders vacancy with someone who would caucus with Democrats.)

"I can't imagine Senator Schumer would be happy with any one of his members being poached by the administration, as we're moving into a new Congress where they want to hit the ground running,” Jim Manley, a former Senate Democratic leadership aide, told ABC News.

The value of a single Senate seat isn’t lost on Biden, allies say. In addition to his decades in the Senate, he served as vice president when the death of Sen. Ted Kennedy, D-Mass., denied Democrats 60 votes in the Senate and complicated the Obama administration's health care push. A Republican eventually won the special election, flipping Kennedy's seat.

“Joe Biden understands the Congress. I would be shocked if he did anything that made it more difficult for him to pass legislation," former Sen. Barbara Boxer, D-Calif., told ABC News.

While senators from solidly Democratic states could be safer picks for Biden because their replacements would have an easier time keeping the seats in the party, any nominees from the Senate could also hurt Democrats’ chances to capture the majority in 2022, when they will be competing for GOP-held seats in Florida, Wisconsin, Ohio and Pennsylvania.

“For Democrats to pick up (or retain) the chamber in 2022, they'll need everything to go right, and since they'll be holding the White House, history is against them,” said J. Miles Coleman, associate editor at Sabato's Crystal Ball, in an email, noting that midterm elections are historically unfriendly to presidents in their first term.

A razor-thin House majority

While votes are still being counted in New York and California, House Democrats, who were expected to expand their ranks in November, will almost certainly begin the next session of Congress with one of the smallest majorities in two decades.

Democrats could end up with a 222 or 223-seat majority, giving the party either four or five votes to spare on any vote along party lines.

If Biden were to pick any representatives for his Cabinet or administration, their seat would be left vacant until a special election is held -- meaning even if a seat will surely be filled by another Democrat, the party would be down a vote in the House for weeks until a replacement is elected.

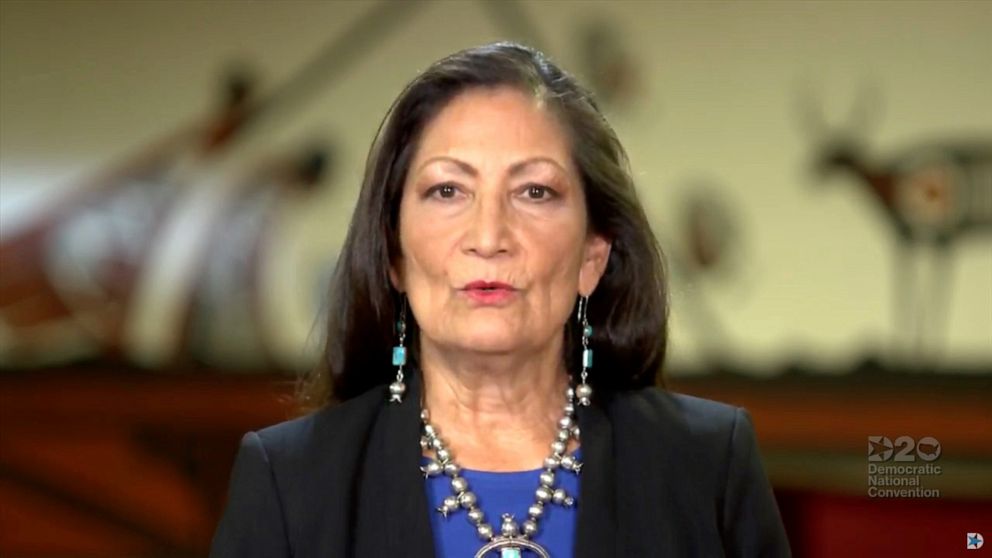

He’s already tapped Rep. Cedric Richmond, a Democrat from a solidy-blue Louisiana district, for a senior position in his White House. But others, like Rep. Deb Haaland, D-N.M., who is favored to lead the Interior Department — would further narrow Democrats’ majority and raise the stakes of every vote in the chamber.

Democrats already face intra-party division and would only be able to afford a handful of defections from Democrats who buck leadership during votes next year. Vacancies would narrow that padding.

The slim majority also almost certainly closes the door on potential administration jobs for Democrats like Reps. Katie Porter, D-Calif., who has been floated to lead the Consumer Financial Protection Bureau, or Ron Kind, D-Wis., whose name has been mentioned for the Office of the United States Trade Representative. Both members won reelection in GOP-leaning districts.

“In the case of the House, it might not be the majority [that is lost], but it can signal early weakness for the party,” said Jacob Smith, a Duke University assistant research professor of statistical and political science.

For nearly a century, 30% of seats left open by elected officials who left their positions to join a Cabinet were flipped by the next general election, according to a study of special elections conducted by Smith and other researchers at Duke University and Michigan State University.

One recent example of such a political flip was the Alabama Senate seat held by Doug Jones, a Democrat who won a special election against all odds two years ago for a seat once held by Jeff Sessions, the staunch Republican who left Capitol Hill to serve as President Donald Trump’s first attorney general.

But while he lost reelection earlier this month, Jones has found a way onto Biden’s short list for attorney general — underscoring how Biden could tap retiring lawmakers, rather than sitting ones, to fill his administration without jeopardizing the balance of power in Congress.

“My advice to a president in his circumstance would be to look to ex-politicians or soon to be ex-politicians, so someone like Heidi Heitkamp in North Dakota, who’s in the mix for agriculture secretary," or Jones, said Smith.

That doesn’t mean dynamics couldn’t change over the four-year term, particularly around special elections and midterms, if Democrats win back a deeper majority in the House or flip the Senate.

“Some of the senators who might normally be considered might be asked to wait until the margin is a little bit larger,” Landrieu, the former senator from Louisiana, said.

ABC News' Molly Nagle contributed to this report.