The Kentucky Derby's rich history of diversity

The annual race is about more than large hats and mint juleps.

— -- Many know the Kentucky Derby as an over-the-top horse race held in the spring, where -- in between sips of mint juleps -- people dressed in huge hats and pressed outfits cheer as racehorses run around a dirt track.

But the derby, which is the oldest continuous sporting event in America, is steeped in a diverse history and tradition that runs deeper than fancy headwear, expensive beasts and boozy drinks.

The first Kentucky Derby was held on May 17, 1875, at Churchill Downs, a thoroughbred racetrack in Louisville, Kentucky. Typically, horses that are about 3 years old compete in the event, where they are required to run the 1.25-mile-long track as quickly as they can.

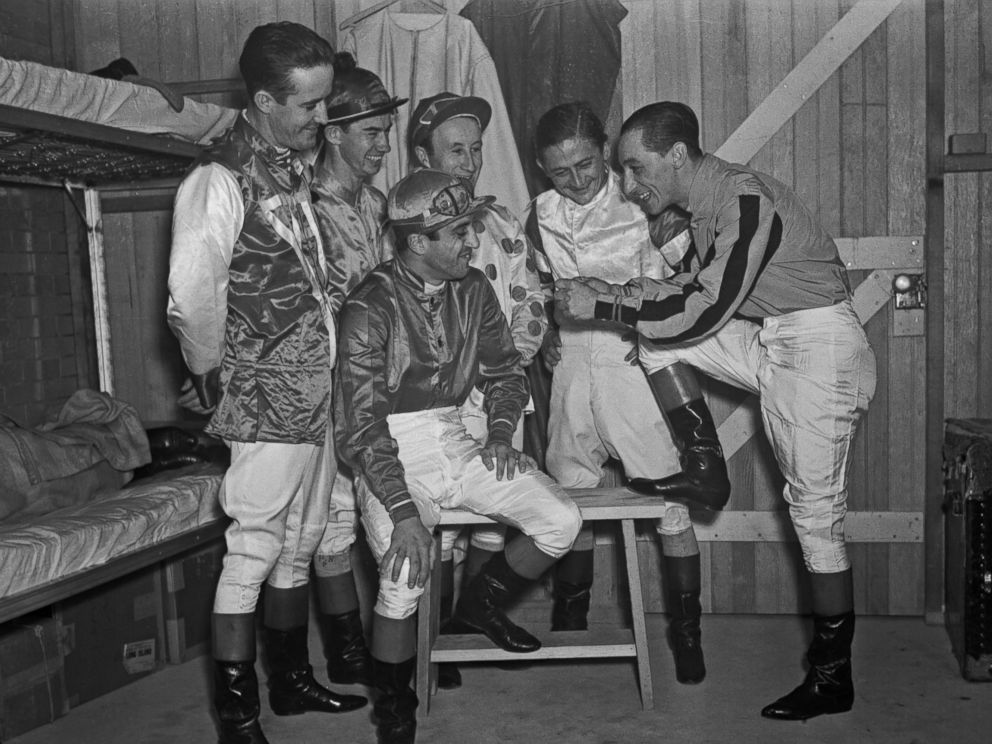

And even though the horses and the owners get a lot of the glory, a sometimes-overlooked part of the winning equation is the jockey. Jockeys often work with the horses, sometimes from birth, to get them ready for “The Most Exciting Two Minutes in Sports,” as the race is sometimes referred to colloquially.

What you may not know is that jockeys, historically, have been a diverse group of competitors, possibly one of the most diverse groups in all of sports.

Black jockeys dominated the Kentucky Derby at its start

Horse racing grew in popularity in the South before the Emancipation Proclamation. Slaves often maintained the horse’s stables and worked with the thoroughbreds, which made them the best people to keep the horses calm before, during and after races. Subsequently, most of the first jockeys were black.

In 1863, 3 million slaves were freed, thanks to President Abraham Lincoln's executive order, which meant these men and women had to start finding a way to support themselves. Due to their familiarity with horses, many newly freed slaves took to racing horses and raising them as careers.

In that first "Run for the Roses" -- a nickname coined by a journalist trying to describe the elaborate rose garland draped over horses after they win -- Oliver Lewis rode the horse Aristides to victory. Lewis, who was 19 years old at the time of the race, was one of 13 black jockeys in that inaugural Kentucky Derby. The other two jockeys in that race were white.

Black jockeys won half of the first 16 Kentucky Derbys, and one of those men, Isaac Murphy, who was the first to win the Kentucky Derby in successive years in 1890 and 1891, also became "the first black millionaire athlete," according to his biographer, Joe Drape.

Murphy, at the peak of his career, received a yearly salary of about $10,000 to 20,000 not including bonuses, which equates to about $260,000 to $515,000 in 2017. At the time, this made Murphy the highest paid jockey in America.

Black jockeys' success at the sport did not go unnoticed by their white counterparts, and as horse racing gained popularity, they were slowly pushed out.

Chris Goodlett, the senior curator of collections for the Kentucky Derby Museum, said racism was to blame for the decrease of black jockeys in the derby.

"Racing becomes more of a profession, so white jockeys become more interested," Goodlett told ABC News. "And when Jim Crow laws came in after the Civil War, racism was the main reason [for the decline of black jockeys.]"

According to Goodlett, Jimmy Winkfield -- who was the last African-American to win the Kentucky Derby in 1902 -- was racing outside of Chicago when he was pushed against the rail "as an intimidation tactic." Goodlett told ABC News the combination of potential injury to the jockey or the horse made fewer black men pursue becoming a jockey.

Not one black jockey raced between 1921 and 2000, until Marlon St. Julien saddled up for the derby.

The late Arthur Ashe, former professional tennis player and author of "A Hard Road to Glory: A History of the African-American Athlete," said the decrease in the number of black jockeys is "the saddest case" of discrimination in American sports.

"Black domination of horse racing then was analogous to the domination of the National Basketball Association today," Ashe wrote in the book, originally published in 1988. "Subsequently, the Jockey Club was formed in the early 1890s to regulate and license all jockeys. Then one by one the blacks were denied their license renewals. By 1911 they had all but disappeared."

For context, the MLB, the NFL and the NBA were not integrated until the 1940s. The NHL wasn’t integrated until the late 1950s.

"Hopefully, we will have more African-American jockeys returning to the race," Goodlett said. "Diversity will continue in the jockey profession for the foreseeable future."

Latino jockeys rise to prominence

As black jockeys waned, Latino jockeys began to take their place.

In 1963, Braulio Baeza of Panama City, Panama, won the Kentucky Derby as well as the Belmont Stakes. He set the stage for various Latinos to consider a career in horse racing.

When President Dwight Eisenhower presented Baeza with the trophy at Belmont, he spoke Spanish to him, according to the Lexington Herald-Leader. Eisenhower spent part of his military career in the Panama Canal Zone in the early 1920s.

"He said, 'Yeah, I speak Spanish,'" Baeza told the Lexington Herald-Leader in 2013. "When he talked [in] Spanish to me … that made [the win] even better."

Since Baeza's win, more Latino jockeys were inspired to become professional jockeys in America.

In fact, every winning jockey from 2011 until 2018 has been Latino: John Velazquez (Puerto Rico), Mario Gutierrez (Mexico), Joel Rosario (Dominican Republic) and Victor Espinoza (Mexico). (Gutierrez and Espinoza have both won twice since 2011.) In 2018, Mike E. Smith, an American, won riding Justify.

"If horses could talk, they would surely speak Spanish," Bob Baffert, the trainer of Triple Crown winner American Pharoah, told ESPN, alluding to the large number of Latinos involved in the sport.

In the 2017 Kentucky Derby lineup, nearly half of the jockeys were Latino, four were from Europe, one was from Jamaica, and the remaining seven jockeys were born in the U.S. In 2018, half of the Kentucky Derby jockeys were Latino, six were American, two were French, one was British and one was Irish.

Goodlett said the infrastructure in Latin American countries lends itself to yielding a great deal of elite jockeys.

"There is racing in Central and South America," Goodlett told ABC News. "There were also jockey schools in that area that go back decades."

For comparison, there is only one professional jockey school in the U.S., the North American Racing Academy.

Female jockeys have raced alongside men in the Kentucky Derby for decades

The first female to ride a horse in the derby was Diane Crump in 1970. Many women had raced alongside men before then, but it took a lawsuit in the late 1960s to allow women to become licensed jockeys to raise the number of females in the sport.

Since then, there have been a total of six women who rode in the Kentucky Derby: Diane Crump, Patti Cooksey, Andrea Seefeldt, Julie Krone, Rosemary Homeister Jr. and Rosie Napravnik.

As of 2018, no female jockey has ever won the Kentucky Derby, but in 2013, Napravnik placed fifth -- the highest place of any female jockey in Kentucky Derby history.

However, women are at a distinct disadvantage because of their body fat composition, which is typically higher than a man's, according to the North American Racing Academy. A successful jockey will weigh so little that the horse will barely feel him or her on its back.

"A horse is not going to be able to perform at its optimum peak if it's carrying 100-something pounds," Hall of Fame rider Chris McCarron told ABC News.

The North American Racing Academy prefers riders weigh less than 112 pounds. Body fat expectations are far more rigid than other athletes, on par with the lowest percentage of body fat necessary to even survive.

"Your typical male jockey has a body fat percentage that ranges between 3 and 7 [percent]," McCarron said. "The girls are between 8 and 12 [percent]." The average American's body fat percentage is around 18 percent for men and 25 percent for women.

The Kentucky Derby requires that a jockey not weigh more than 126 pounds, including his or her equipment.

Vanessa Reill, who attended the North American Racing Academy back in 2013, said she struggled meeting the weight requirements during her schooling.

"I've stopped eating as much chocolate as I used to," she told ABC News. "And just trying not to go over 1,500 calories a day."

But the pressure to stay thin means eating disorders are common among jockeys.

"Unfortunately, bulimia is a pretty prevalent problem among jockeys and taking diuretics [is as well,]" McCarron said.