Inside online shaming, and the 'viral infamy' that follows

The incidents themselves may fade from memory, but the viral posts live on.

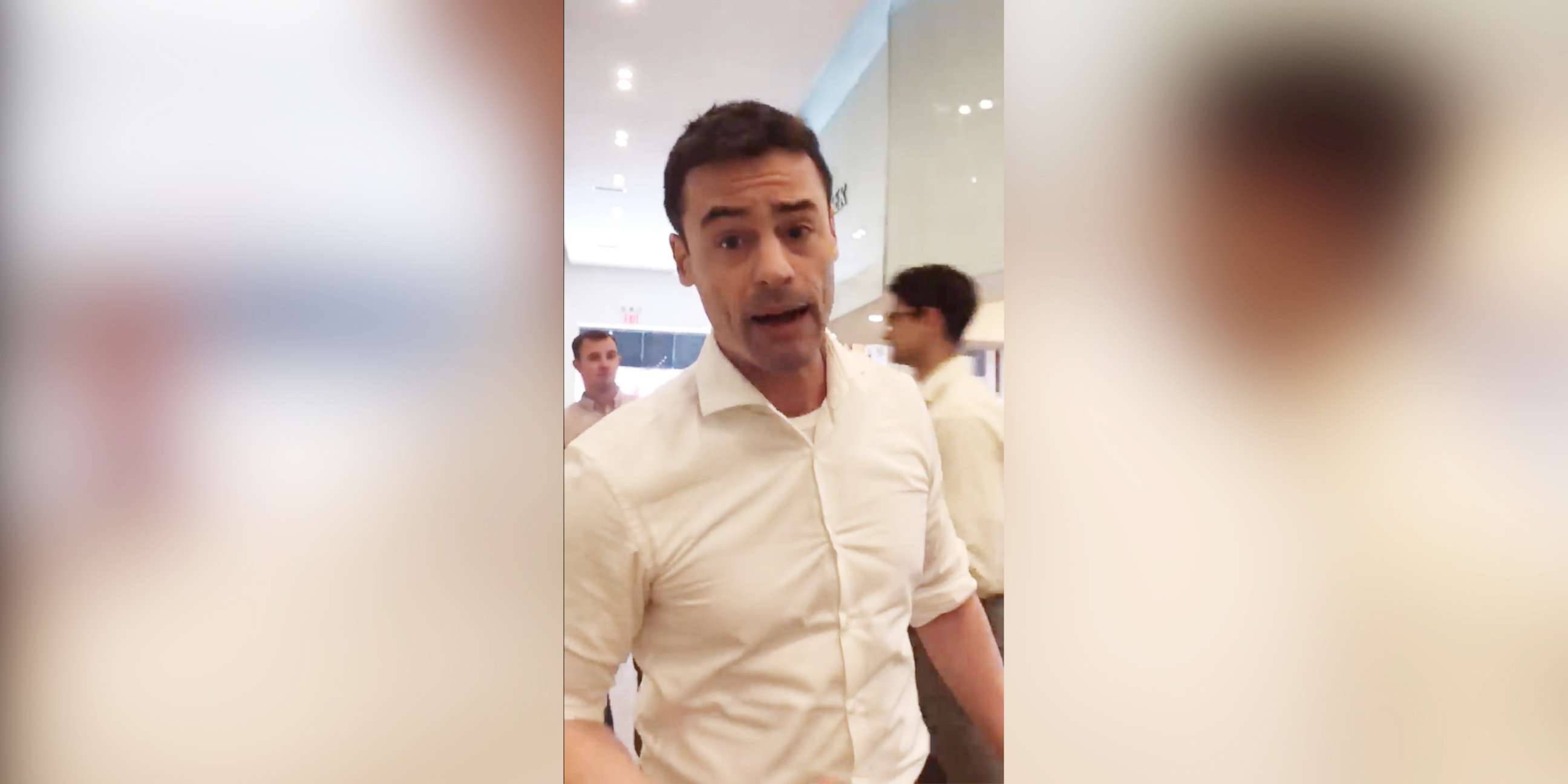

A year after the video of him confronting a Chick-Fil-A employee over the fast-food chain's anti-LGBTQ stance went viral, Adam Mark Smith wasn't sure he wanted to live anymore.

He had lost his job, become the subject of death threats and had photos of his children published online. Many of the commenters told him he was a "piece of garbage," and others suggested he kill himself.

"As a result of making this mistake, and as a result of going through that shaming and that super dark night of the soul, I definitely questioned whether I should live any longer," Smith told ABC News. "I contemplated suicide about a year after, and I had never had those thoughts before."

The video, which he said he assumed would only be watched by his five YouTube followers at the time, had become a lightning rod. In it, Smith orders a free water at the drive-thru, taking the opportunity to tell the attendant, in part: "Chick-Fil-A is a hateful corporation ... I don't know how you live with yourself and work here. I don't understand it. This is a horrible corporation with horrible values. You deserve better."

By the time Smith got back to his office that day in 2012, the medical device company where he was chief financial officer had already received bomb threats. He was fired that same day, and said he also lost $1 million in stock options.

“I shut down hard in my life,” he added. “It was like being flayed in the flesh and everyone gets to see all of my problems, and comment, and judge.”

Two days after posting the video, he posted a nearly eight-minute-long apology to the drive-thru attendant, a woman named Rachel, which also went viral. The woman told Fox News days later that she forgave Smith.

But still, the shaming continued.

"I apologized, but was that good enough? For others, it was not good enough," Smith said. "Why doesn't an apology, even if it's real, authentic and made two hours afterwards, why doesn't it just calm everyone down?"

The answer is a complex one, but the magnifying effects of the online world have a lot to do with it, according to Dr. Krystine Batcho, a professor of psychology at Le Moyne College in Syracuse.

"There's this feeling that it's 24/7, it can go anywhere, and it can stay around forever, and there's no way out," Batcho told ABC News. "In other words, someone might be viewing a video or reading about someone's awful behavior, and that person might be reading it a year and a half after it occurred. It's a complete stranger, maybe a thousand miles away, and the person who is being shamed has no recourse. They can't defend themselves, argue with this person, or say, 'Let me explain myself.'"

"In that sense, social media is a form of public shaming that you could argue that is one of the most powerful weapons -- if someone wanted to use shaming as a weapon -- that we have," Batcho added.

'A way of outing undercover racists'

It's a familiar cycle -- act, upload, be shamed, apologize, hide. While the acts that made people the subject of online shaming may fade from public memory, the viral videos, pithy hashtags and startled screenshots of their faces live on.

For people whose outbursts are captured on video and shared on social media, the consequences offline are all too real. And while many agree that people should be called out for expressing racist, sexist, homophobic, anti-immigrant or other hateful views, there is debate over whether their lives should be permanently ruined because of it.

In May, Manhattan attorney Aaron Schlossberg's anti-immigrant rant at a Midtown Manhattan restaurant against people speaking Spanish went viral; several lawmakers called for him to be disbarred and activists crowd-funded a mariachi band to show up at his office.

Schlossberg later issued an apology, saying: "Seeing myself online opened my eyes -- the manner in which I expressed myself is unacceptable and is not the person I am."

Jennifer Schulte, a white woman, called the police on a group of black people who were legally barbecuing at a public park in Oakland. She was branded "BBQ Becky" and her image was photoshopped into memes across the internet.

An unidentified white woman in Georgia who threatened to report a black woman for smoking in a parking garage was dubbed "Newport Nancy."

Monique Judge, a columnist who has written about many of these cases for The Root, said online shaming is a tool in confronting racist behavior.

"These things go viral because they illustrate the type of micro-aggressions black people experience every day. They are indicative of the way white women use their privilege and weaponize law enforcement against black people," Judge told ABC News via email. "Calling this behavior out in an online format brings attention to it. It is also a way of outing undercover racists. Those who uphold white supremacy deserve to be called out for it."

'Viral infamy taking down lives'

In June, Alison Ettel made headlines after calling the police on an 8-year-old African American girl for selling bottled water without a permit. The girl's mother, Erin Austin, said Ettel's decision to call the police was racially motivated, a claim Ettel denied. The video, shot by Austin and uploaded to social media, quickly went viral, and Ettel was branded "Permit Patty."

"Calling the police on any person of color these days is an issue. They come, they shoot first and they ask questions later," Austin told "Good Morning America". "Knowing that and knowing everything that's going on in the media, why would you call the police on a child of color?"

Ettel released a statement apologizing for her actions.

"I have no problem with enterprising young women. I want to support that little girl. It was all the mother and just about being quiet," Ettel's statement read. "I had been putting up with this for hours, and I just snapped."

"I completely regret that I handled that so poorly," Ettel's statement continued. "It was completely stress-related, and I should have never confronted her. That was a mistake, a complete mistake."

Ettel initially said she had only pretended to call the police, but audio of a 911 call obtained by KTVU shows she did place a call, saying "I have someone who does not have a vendor permit that’s selling water across from the ballpark."

The San Francisco Department of Emergency Management confirmed to ABC News that a call was made.

"A San Francisco 911 dispatcher received a call stating that someone was selling bottled water without a permit. Selling bottled water without a permit is not a police, fire, or medical emergency. As a result, the dispatcher transferred the call to San Francisco’s Police Non-Emergency dispatch. The call disconnected before reaching a non-emergency dispatcher," a Department of Emergency Management spokesperson told ABC News.

After the incident, marijuana dispensaries in California announced they would no longer sell products from Ettel's cannabis tinctures company, TreatWell. On Tuesday, TreatWell announced in a statement that Ettel had resigned.

Neither Ettel, Schulte nor Schlossberg responded to ABC News' request for comment for this story.

The swiftness and intensity of the backlash -- and the speed at which it can travel online and stay there for decades -- also has consequences, experts say.

"This is the problem with the internet. Years ago, if you were caught doing what Alison [Ettel] did, it would have been contained to the little city, to the little area that she lives in. Today, it's magnified by a billion," Sue Scheff, the author of "Shame Nation," told ABC News. "We're seeing this viral infamy happening and taking down lives."

Scheff, the founder of Parents’ Universal Resource Experts, won a landmark case after she was defamed online by a mother who flooded parenting forums with comments calling Scheff a "crook" and accusing her of kidnapping and abuse. But even though she was vindicated in court in 2006 and was awarded $11.3 million in damages, many of those negative things about her still popped up in Google searches.

To Scheff, that underscores an important reality.

"Once you go online, Google can determine who you are," Scheff said. "Ninety-eight percent of Americans are now armed -- and I use that word, armed -- with smartphones. We are not afforded the luxury of walking down the street and having that 'oops' moment."

'I have to own it'

A single moment can quickly become a person's entire identity online. Juli Briskman was biking near her home in Sterling, Virginia, on Oct. 28, 2017, when President Donald Trump's motorcade passed her. She raised her left hand and gave Trump the middle finger in a universal gesture of disrespect.

She said it was an expression of her "frustration with Trump and his administration and the choices they were making or failing to make."

Briskman said at the time, she didn't know that the press was following behind and had snapped a photo. She didn't think much of it until the next day when friends began asking if it was her.

"I started to watch the likes and the retweets of that original photo just keep growing and growing, and I started to see the photograph in so many places," Briskman told ABC News. "I sort of thought that was the end of it, but then it just kept getting more and more popular. Then the yoga studio where I was working at the time asked me to take them off my Facebook page as my employer because they were getting threatening emails and phone calls, that people were going to boycott the studio because I was working there."

She was ultimately fired from her other job as a government contractor. That's when she decided to go public and say that the woman in the photo was her. Support poured in, she said, but so did the threats.

"I got maybe 85 percent good comments, and maybe 15 percent bad comments. I got voice messages at home from unidentified numbers, I got a lot of mail in the negative," Briskman said. "For a while, I had extra sheriffs' cars in front of the house, patrolling the neighborhood."

Many of the negative messages contained not only threats but insults about her body as well.

"I made a mental note when all of this was happening that a lot of the negative comments referred to whether I had a fat a-- or whether my shoulders were bigger than my butt," she said. "It made me feel like you obviously don't have a salient argument because what you decide to do is threaten me. And that is so common when women come into their power."

Briskman is now suing her former employer, Akima LLC, for wrongful termination and for severance. Akima LLC filed a motion to dismiss Briskman's suit.

On June 29, a judge ruled to overrule the motion related to severance and sustain the part related to her wrongful termination claim.

Briskman's attorneys said they are now deciding how to proceed and whether to appeal the decision. Akima LLC did not respond to ABC News' request for comment.

Whatever the outcome of the lawsuit, Briskman said she has to live with her decisions.

"I have to own it," Briskman said. "Maybe 10 years from now, I will be like, 'Darn it, that's the first thing that comes up about me.' But I'm 51 years old, and I am just going to live my truth at this point, I'm not going to try to hide it. You can't hide things on the internet anyway."

Thanks to a 2014 European Court of Justice ruling, there is a so-called "right to be forgotten" in the EU that allows people to ask search engines to remove certain results about them. The U.S. has no such law, although a 2015 poll by Benenson Strategy Group and SKDKnickerbocker found that 88 percent of Americans were in favor of such a policy.

'We need to put down our pitchforks'

Of course, not all outbursts are created equal, and there is a huge difference between confronting discriminatory policies and actually discriminating against someone yourself. But Batcho warned it’s a dangerous place to be if people can never be forgiven for their mistakes, even ones that go viral.

She added that once people have piled on, it makes it harder for a person’s apology to ever be enough.

"It isn't just the harm to the victim who is shamed," Batcho said. "The person doing the shaming is harmed, too."

But Judge said she has not yet seen a situation where online shaming of people accused of racism has gone too far, and that whether their apologies are accepted should depend on the circumstances behind them, citing Ettel’s case as an example.

“#PermitPatty only became contrite when it started affecting her business and her pockets. Prior to that, she was perfectly content to weaponize the police against an 8-year-old girl. There were many points in her actions when she could have stopped, but she didn't. Her apology was simply made to try and mitigate her losses, and that is not a real apology,” Judge said.

Scheff said that the one upside of online shaming could be that it forces people to be more civil to each other.

"We have to be self-aware. I think it could make us a better person, too," Scheff said. "Maybe what it's doing now is that people need to start checking in with themselves and just start being nicer to everyone. Maybe it's going to really start forcing us to be more civil with each other."

Even after the backlash both faced, neither Briskman or Smith said they regret taking a stand, although Smith said he would go about it differently in the future.

“The part I regret about the video is how I conducted myself with the young lady and how I was being arrogant and condescending toward her. That’s the part I regret. The other part, in terms of standing up for human rights and equality, is something I do not regret and cannot imagine myself ever regretting,” Smith said.

Briskman said she would do it again, and has since participated in protests against Trump in her neighborhood.

“With this whole thing, a lot of my family says, 'You need to protect your kids. You need to get off social media.' You know what, I am right, I have solidness in my core that I am right about this, and I'm allowed to speak against this president. That's our right of free speech as Americans, and I'm not going to have anyone tell me I can't do that,” she said.

But being the subject of online shaming can be a lonely place, no matter who you are or what you did. Smith, now a life coach, said he reaches out to people who are being shamed online a few times a month to let them know he has been there.

"Whoever won the shaming lottery today, I'm telling you, they will never be the same. They have such dark nights ahead of them. It's going to be the hardest thing, if they're anything like me," Smith said. "They will question everything, if life is worth living. So if you just have that truth, that they are going to possibly contemplate suicide, could you just stop and just breathe and maybe send them an 'I forgive you' comment? Or an email that says, 'I make mistakes, too.' Because that's the only way we are going to get out of that mob mentality."

Scheff agreed: "We need to put down our pitchforks. Everyone out there needs to start gaining more empathy. We're all under so much angst."