What to know about police reforms after George Floyd's death and why 'defunding' might be a solution

"This is about dialing back police power," Alex Vitale said.

Police brutality and use of force have long been issues in the United States.

In the aftermath of Eric Garner and Michael Brown's deaths at the hands of police officers six years ago, reforming law enforcement became a rallying cry.

The horror of seeing Garner say "I can't breathe" and the unarmed Brown being gunned down galvanized activists who called for reform.

Yet as the years went on, more deaths followed -- Tamir Rice, Alton Sterling, Philando Castile, Stephon Clark and Breonna Taylor.

Most recently, George Floyd's shocking death, calling "I can't breathe," just like Garner, as a Minneapolis police officer knelt on his neck for nearly 9 minutes, sparked international outrage and renewed calls for wide-ranging reform, including the controversial concept of defunding the police.

The message, in its simplest form, boils down to diverting funds away from police budgets and investing them into community resources, according to Alex Vitale, a professor of sociology and the coordinator of the Policing and Social Justice Project at Brooklyn College and the author of "The End of Policing."

Vitale told ABC News that defunding the police has so much traction this time around after it became clear that other reforms were not working.

"It's becoming increasingly difficult to say with a straight face that there's nothing wrong with policing and that we just need to restore people's confidence in police," Vitale said. "No one on the streets, no one in these communities is really buying that anymore."

Former law enforcement officers have said that reforms have worked and taking funds away from police would hamper on community efforts already in place.

Yet as calls to defund the police have grown, ABC News looked at what reforms were in place after 2014, how effective -- or ineffective -- they proved to be and where both politicians and activists stand now.

What reforms were in place after Garner and Brown's deaths?

Body cameras and implicit bias training were two reforms that were widely discussed in the wake of Garner and Brown's deaths, according to Vitale.

Garner, 43, who had been accused of selling untaxed cigarettes, died after he was placed in a chokehold on July 17, 2014 by undercover officer Daniel Pantaleo, who is white. Garner could be seen on bystander video crying "I can't breathe" while still in the chokehold, which had been banned by the New York Police Department, before his body went limp. Garner was taken to a hospital where he was pronounced dead. Pantaleo was fired in 2019, more than five years later, but did not face either state or federal charges in the case.

Brown, 18, was shot to death by then-Ferguson police officer Darren White in Ferguson, Missouri, on Aug. 9, 2014. Wilson, who is white, was investigating a complaint of shoplifting at a convenience store and claimed Brown matched the description of one of the suspects when he saw the teenager walking down a street. Wilson said Brown charged at him at one point and Brown, who was unarmed, was shot six times.

Vitale said many believed the "procedural reforms" of body cameras and implicit bias training were solutions to issues within police departments, according to Vitale.

"The mayors and police chiefs and a lot of community leaders and the president [Barack Obama] were like, 'No, no. We can fix this. We can fix this with procedural reforms,'" he said.

One ABC News story from 2014 highlights the expectations many had over body cameras, saying that they had won praise from civil rights activists and police union officials to help better document police interactions. And the White House believed that they would help improve community-police relations.

By 2016, 47% of the 15,328 general-purpose law enforcement agencies in the United States had acquired body-worn cameras, according to the U.S. Department of Justice.

Yet some research has offered disappointing results.

In a study of the Metropolitan Police Department in Washington D.C., one of the largest in the country, researchers found body cameras did not have a "statistically significant effect" on police officers' behaviors.

The study, published in 2017, was conducted over seven months with a little more than 1,000 police officers who were randomly assigned cameras and another thousand who were not.

"As such, our experiment suggests that we should recalibrate our expectations of BWCs (body-worn cameras). Law enforcement agencies (particularly in contexts similar to Washington, DC) that are considering adopting BWCs should not expect dramatic reductions in use of force or complaints, or other large-scale shifts in police behavior, solely from the deployment of this technology," according to a conclusion of the study, which was published in 2017.

A 2018 paper from the National Institutes of Justice said that while the cameras may offer benefits to law enforcement, more study was needed. And a 2019 review of 70 studies found that "BWCs have not had statistically significant or consistent effects on most measures of officer and citizen behavior or citizens’ views of police."

Minneapolis police say there is body camera footage of the Floyd incident (two of the officers around Chauvin can be seen wearing cameras), but it is not clear what it shows. It is also not clear if the other two officers, including Chauvin, were wearing cameras.

Implicit bias training was touted in President Obama's Task Force on 21st Century Policing, which was published in 2015, and grew after Garner and Brown's death, according to Vitale.

While many departments have adopted some form of implicit bias training, a 2016 study found that "there are as yet no known, straightforward, effective intervention programs" and that there were "several interventions" aiming to reduce biases that "warrant further investigation in the policing context."

Research shows that as of 2019, black people still faced a disproportionate risk when dealing with police.

Black men are about 2.5 times more likely to be killed by police over their life course than white men, according to an article published in August 2019 in the peer-reviewed Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America, which reviewed data from 2013 to 2018.

Other research shows that black people are 1.3 times more likely to be killed by police while unarmed than white people, according to the database Mapping Police Violence, which reviewed killings from 2013 to 2019.

De-escalation training has also been touted as a reform effort, especially in recent years. The training focuses on slowing down actions before they escalate into a situation where an officer feels force is necessary, according to a 2018 report from the U.S. Commission on Civil Rights.

Law enforcement experts agreed that training that includes more emphasis on de-escalation is positive in terms of reform, according to the report. However, no studies have conclusively shown that de-escalation training lowers the likelihood of an officer’s use of force, but some suggest it can help, the report stated.

At the time that report was released, 34 states still did not require that training. In states that do require it, the required house of training can range from no minimum requirement to three hours every three years up to four hours every year.

Even if encounters with police do not end in death, an ABC News analysis showed that in 800 jurisdictions, black people were arrested at a rate five times higher than white people in 2018, after accounting for the demographics of the cities and counties those police departments serve. In 250 jurisdictions, black people were 10 times more likely to be arrested than their white counterparts.

Robert Boyce, a retired NYPD chief of detectives and ABC News contributor, said there have been reforms that have brought about positive change, such as raising the age of criminal responsibility to 18 years old, which was done in 2018. New York had been one of only two states that automatically prosecuted 16- and 17-year-olds as adults, according to Gov. Andrew Cuomo's office.

But he objected to the proposal of defunding the police.

"Defunding the police is a false narrative. It's a problem because it doesn't make any sense," Boyce said. "Policy should be cut by analysis and common sense."

When asked if he thought diverting some of NYPD's nearly $6 billion budget to community resources was a realistic ask, Boyce said the New York police department already has a community affairs bureau.

He said that bureau, which connects officers with faith-based and community leaders, was crucial in certain cases.

"I needed that branch to say, 'Hey, we care about you. We're here to help,'" Boyce said. "These are integral parts of police departments that you have to have, so it's existing now."

Community policing, with its emphasis on establishing contacts between officers and the community to foster good will and share in the duties of public safety, has been a reform concept for decades, but as of 2016, while 87.4% of large departments had dedicated personnel, only 28.5% of small departments had.

Yet after Floyd's death on May 25, the conversation drastically turned more to defunding the police.

Vitale said the momentum for defunding the police arose, in part, because "everyone who had been doing work in the community around the issue of policing has moved way beyond body camera and implicit bias training. They came out and said, 'No. We need to defund police and put that money into communities.'"

According to the Urban Institute, a think tank, spending on police has increased from $42 billion in 1977 to $115 billion in 2017 (in inflation adjusted dollars). This is despite crime tailing off since the 1990s.

What are politicians doing now? What are activists calling for?

It's a mixed bag. In some cases, the traditional calls for reform have been rehashed.

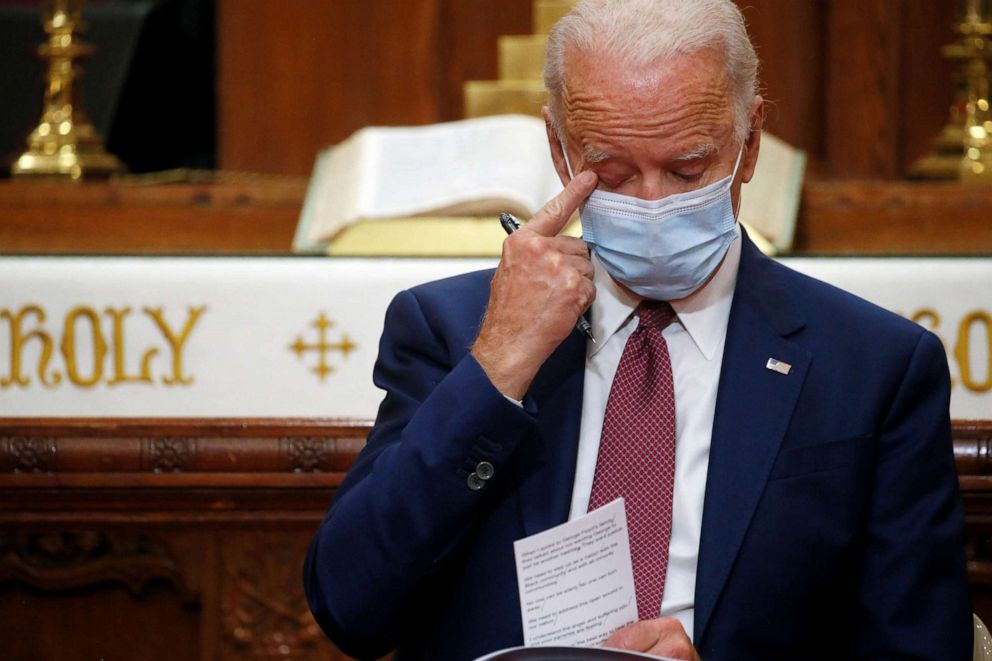

Presumptive Democratic nominee and former Vice President Joe Biden has said he doesn't support defunding the police. On Wednesday night at a virtual NAACP town hall on systemic racism, Biden said instead for police departments to get funds "you'd have to meet certain basic minimums."

He gave the example of eliminating chokeholds. However, even prohibiting chokeholds does not mean they will not be used -- as the death of Garner proved.

Congressional Democrats also unveiled a police misconduct reform bill. However House Speaker Nancy Pelosi dismissed the idea of defunding and said Democrats “want to work with our police departments.”

House Democrats have introduced a series of sweeping reform proposals including the George Floyd Law Enforcement Trust and Integrity Act, which includes national policing standards, required use of force data reporting, data on police stops and require the Department of Justice to create a task for overseeing the investigation and prosecution of misconduct. Other measures take on the issue of qualified immunity, which shields cops from scrutiny and outlaws chokeholds.

A Republican Senate proposal would make lynching a federal crime, give departments incentive to report serious use of force and increase funding for body cameras, among other things.

Other politicians have appeared to be more open to the idea of divesting funds from police and putting them into community resources. New York City Mayor Bill de Blasio announced four efforts at police reform, including shifting funds from the NYPD to youth and social services. De Blasio did not specify an amount.

Several other cities and jurisdictions have announced action including Seattle calling for an independent prosecutor for police offenses and Sacramento and New Jersey prohibiting chokeholds.

In Minneapolis, nine out of 13 city council members pledged they would disband the police department.

City Council President Lisa Bender said they were committed to "end our city's toxic relationship with the Minneapolis Police Department, to end policing as know it and to recreate systems of public safety that actually keep us safe." Details for how this will be done have not yet been revealed.

Molly Glasgow, who works with MPD 150, an organization working towards a police-free Minneapolis, told ABC News that the calls to defund the police are because "we see that there is this cycle of brutality, or a murder, happening and then protests happen and people calling for changes and then there's police reform, but then things are stagnant and slide back."

"It's this cycle we've seen played out again and again," she said.

Glasgow added that when people initially hear the phrase "defund the police," they may think that it's more about doing away with the police than taking away from the police to add to other resources.

"When we talk about abolition, it means dismantling the PD, yes, but it also means investing in and prioritizing community-based initiatives and strategies and programs," Glasgow said.

Vitale said he isn't sure if the movement of defunding the police will bring about sustained change.

However, he believes that more people now understand "this is about dialing back police power, getting police off our necks and putting in place real solutions to our problems to lift up individuals and lift up communities."