'He didn't look dangerous': The truth about serial killer, con man John Robinson

He's accused of killing eight women and giving a victim's baby to his brother.

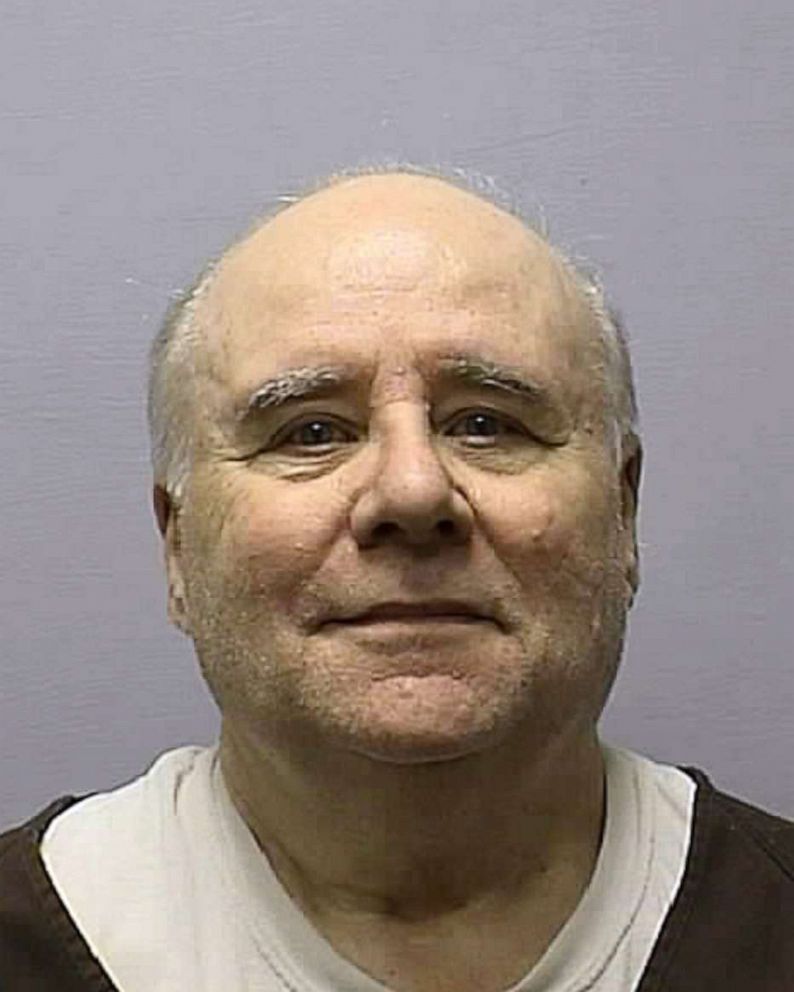

From the outside looking in, John Robinson was the ideal family man.

He coached his four children's various sports teams in the Kansas City area. He was a Sunday school teacher. He even volunteered as a Scoutmaster.

"He didn't look dangerous. He looked like this mild-mannered, grandfatherly guy. He looked like he could be, you know, the clerk at the, at the drugstore," said Tony Rizzo, a former reporter at The Kansas City Star.

But John Robinson was a master manipulator, one who was very good at seeking out vulnerable women, luring them into his orbit and, for some, to their deaths.

"He had this long, long career as this, this con man. ... He would pilfer stamps from, from an employer or money from a potato chip company up in Liberty," said Mark Morris, another former reporter at The Kansas City Star. "If there was a way to, to con somebody, John E. Robinson had already thought it through."

He went to prison in 1987 for fraud and got out in 1993. It wasn't until June 2000, however, that authorities uncovered the bodies of multiple women in barrels on his farm and in a storage locker, and he was finally brought to justice for his most heinous crimes.

Authorities also got another surprise: One of the presumed murdered women had a baby girl at the time of her slaying and the baby was not only alive, but now a teenager living with Robinson's brother.

"I'd say John Robinson is one of the most dangerous criminals that I ever encountered," said Rick Roth, a former Lenexa, Kansas, investigator who worked on the case.

John Robinson meets the queen of England

John Robinson was born in 1943 in Cicero, Illinois, outside of Chicago, and grew up in a working-class neighborhood.

At the age of 14, in a rather extraordinary moment, he traveled as an Eagle Scout to England to sing for the queen at London's Palladium. While backstage at the Palladium, he ran into movie star Judy Garland.

"She kissed him on the cheek and this made a big story in the Chicago papers," said Stephen Singular, who wrote "Anyone You Want Me to Be," a book about Robinson, with writer John Douglas.

In 1964, at the age of 21, John Robinson married Nancy Jo Lynch. He then got a job at a Chicago hospital.

Rizzo, the former reporter, told a story about how, in 1977, a big banquet was held in Robinson's honor in downtown Kansas City at a hotel and he was awarded "Man of Year" for the great work he'd done. But there was a twist: Robinson had made it all up.

"It turned out that it was his own invention," said Rick Montgomery, a former reporter at The Kansas City Star.

In 1984, Robinson put a help-wanted ad in a newspaper for a sales representative job and hired 19-year-old Paula Godfrey. According to police, Robinson told her she would be traveling to Texas for some training. But then, Godfrey disappeared.

"Her father confronted John Robinson, who totally said, 'I don't know what you're talking about.' All of a sudden, these letters started appearing, signed by his daughter saying, 'Oh, I'm OK. I'm fine. You don't need to worry about me,'" said Joyce Singular, who is mentioned as a contributor in "Anyone You Want Me to Be" with Stephen Singular and Douglas.

Around Christmas 1984, three months after Godfrey vanished, Robinson claimed to have started the Kansas City Outreach Program, purportedly to help downtrodden women. He went to several shelters and hospitals telling social workers about the program.

Karen Gaddis, a former social worker, said she was told the program worked with young, pregnant women or women with newborns to help them get back on their feet and find a place to live.

"After Christmas, he called again and talked to me about this young lady that he had gotten from a women's shelter in Kansas City. He said he met with her and she had agreed to go to the program with him," said Sharon Turner-Jackson, a former social worker.

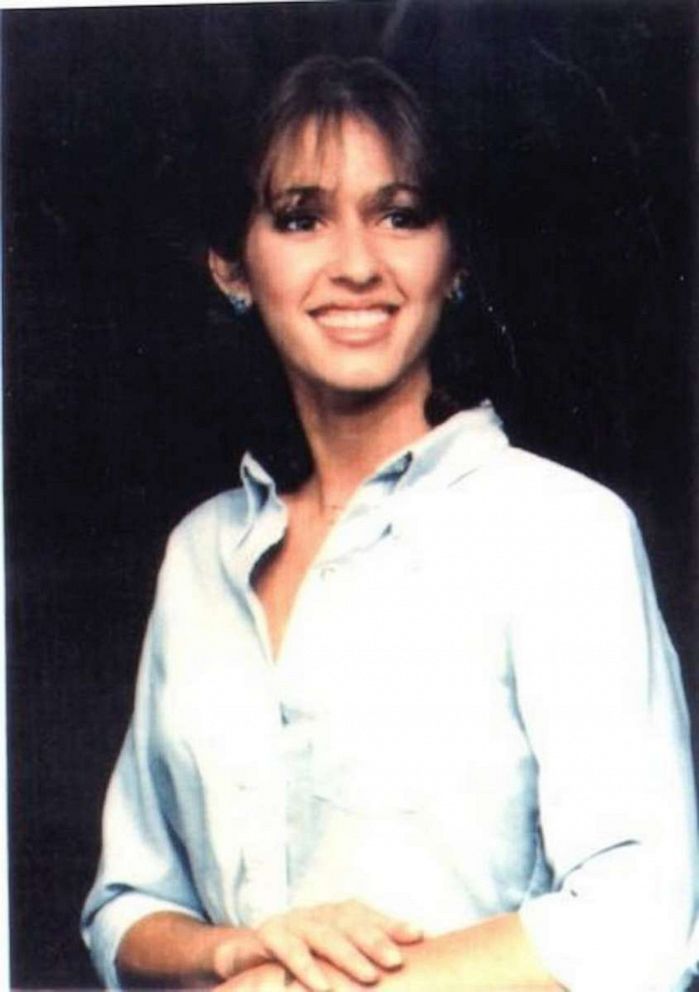

That woman was apparently 19-year-old Lisa Stasi. Gaddis and Turner-Jackson said they had been suspicious of Robinson's desire to find a needy white woman and her baby in time for the holidays and were not the ones who referred Stasi to him. Somehow, Robinson connected with the young woman and put her and her 4-month-old daughter, Tiffany Stasi, up at the Rodeway Inn hotel.

Stasi's family said that one day, they got a call from her. She was crying hysterically and told them that she had to sign four pieces of paper.

"I said, 'Don't sign nothing.' And she was just a crying and then she finally settled down and she says, 'Here they come now,' she said. And she hung up. And that was the last time I heard from her," Betty Stasi, Lisa Stasi's mother-in-law, told ABC News' Primetime in a 2000 interview.

Lisa Stasi disappeared, her family said. They later received a typewritten letter supposedly from Lisa Stasi, according to Roth, the former police investigator.

Cathy Stackpole, the former director of the shelter where Lisa and Tiffany Stasi had stayed, read from the letter she received, purportedly from Lisa, to ABC News in 2000, "I want to thank you for all your help. I’ve decided to get away from this area and try to make a good life for me and Tiffany."

Pat Sylvester, Lisa Stasi's mother, said, however, that Lisa Stasi was not a big letter writer and, "She couldn't type enough to type a letter," Sylvester said in the 2000 interview.

John Robinson goes to prison and finds love

In 1987, John Robinson was convicted on fraud charges after running various scams, according to Stephen Singular, and sentenced to prison time.

That same year, before Robinson was sent to prison, though, a woman in her mid-20s named Catherine Clampitt disappeared.

While in prison, he got a job in the library and started a relationship with Beverly Bonner, who was married to the prison doctor.

After Robinson was released, Bonner left the prison and divorced her husband to be with him. Meanwhile, Robinson's scamming days were far from over.

"John E. Robinson was a practiced liar, a charming practiced liar. He fooled a lot of people in his life," said Morris, the former reporter.

Bonner, too, eventually disappeared. Robinson began collecting her nearly $1,000 monthly alimony checks, according to authorities, and sought out other women. Authorities believe Bonner died in 1994.

With the arrival of the Internet, Stephen Singular said, Robinson set up five computers in his home and several monikers for himself online including Jim Turner and "Slave Master." He would use it to seek out and hook up with women looking for sex.

"He had the whole world of the online, and the BDSM subculture, to be his hunting ground," said author Joyce Singular. BDSM stands for bondage and discipline, sadism and masochism.

Through the internet, authorities said, Robinson met a woman named Izabela Lewicka in 1997. She was a young Polish immigrant and art student living in Indiana.

"He wants her to come to Kansas essentially to be his submissive," Stephen Singular said. "She suddenly disappears as well."

Authorities said Robinson's modus operandi would be to tell the women he could take care of them, and lie about who he was, how much money he had and his background.

"I'm a wealthy businessman. I'm gonna take care of you. You can be my slave. And by the way, we're gonna travel all the time, go to exotic places and just have a wonderful life," Paul Morrison, the prosecutor who handled Robinson's eventual capital-murder case, said of the picture Robinson created for his victims.

Robinson would tell the women that they were going to be seeing the world, sailing on his yacht or flying to Europe. He said they would be so busy, that they needed to sign some blank pieces of paper. He’d later send letters to the women’s families, posing as them, so relatives didn’t think they’d been killed, Morrison said.

"He looks more like the Pillsbury Doughboy than he does, you know, the 'Chainsaw Massacre' guy. ... He's very congenial. He smiles. He laughs. He tells stories. He slaps you on the back. He's got a good handshake," said Steve Haymes, a former district supervisor for the Missouri Board of Probation and Parole, who investigated Robinson starting in 1985.

Morrison said that Robinson scammed Suzette Trouten, 28, of Newport, Michigan, in 1999 by persuading her to work as the caretaker for his supposedly elderly father. But, in reality, his father had been dead for many years by that point. The alternative lifestyle also attracted Suzette Trouten to make the move to Kansas City the following year.

Suzette Trouten's mother, Carolyn Trouten, received emails from her but felt like something was amiss.

"Things weren't worded the way she would word them," her mother told a news reporter at the time. "Everything was spelled right."

When she did not hear from her daughter, she became worried and called the authorities.

"The whole house of cards came tumbling down on Robinson at that point," said reporter Rizzo.

Within days, Morrison, the former prosecutor, said police had organized a task force.

Dave Brown, a police officer who investigated Robinson, told ABC News that Carolyn Trouten had told them to find her daughter's beloved Pekingese dogs, Peeka and Harry.

"Suzette would never have gone anywhere, not sailing, not across town, nowhere without those dogs," Stephen Singular said.

Police would then discover that two dogs had been found abandoned at a trailer park where Robinson lived on March 1, 2000, the same day that Suzette Trouten disappeared.

Animal control was called and workers came and took the dogs. A detective visited a family who had adopted one of the dogs to see whether it belonged to Suzette Trouten.

"He calls Peeka by name," Brown said. "His ears perking up, his tail starts wagging."

The dog ran to the detective. At that moment, Brown said, authorities realized that the dog likely belonged to Suzette Trouten and that she could be dead.

Investigators and her mother were pretty confident that Robinson was involved.

The police started following Robinson, watching his every move including during his trips to 16 acres of property he had in Linn County, Kansas.

Mother of missing woman gets John Robinson on tape

Brown, the investigator, gave Carolyn Trouten a tape recorder to record a phone call Suzette Trouten’s mother would make to Robinson in hopes of finding out what had happened to her daughter.

In one taped phone call, John Robinson told Carolyn Trouten that her daughter had left with someone else to travel the world and had not taken the job he'd offered her.

Carolyn Trouten: "We haven't heard anything in a couple of weeks and I'm really getting nervous."

John Robinson: "Oh hon, don't, don't, you know, I wouldn't get nervous."

Carolyn Trouten: "I'm nervous. Susie always calls me, so-"

John Robinson: "Oh. Well, I, from what I understand they're, they're on a boat somewhere and she couldn't, kinda hard to call."

Carolyn Trouten: "I'm really getting very nervous about this." I don't know if I should maybe call the police or something."

John Robinson: "Why?"

Carolyn Trouten: "Well, because I haven't heard from her and that's not-"

John Robinson: "Honey, she's a-"

Carolyn Trouten: "like Susie."

John Robinson: "Hon, she's a big girl."

Later in the phone call, Trouten asked Robinson whether she should notify someone about her daughter's disappearance.

"Hon, I wouldn't, you know, I really wouldn't, uh, wouldn't worry about it too much," he tells her during the call. "I'm sure that when, when they hit the next place they'll, um, they'll send us a card or call us or email us or something."

Hear this chilling phone call with serial killer John Robinson

Rick Roth, the former Lenexa investigator, said that during the police probe of Suzette Trouten’s disappearance, her relatives started getting letters purportedly from her. Some of them came from Kansas City and others from California.

"All along they said, 'This is not the way Suzette writes.' In fact, in one of the letters that they received, one of the dogs named, it was misspelled. And they knew Suzette would not misspell the name of her dogs," said Brown, one of the police investigators.

During their investigation into Suzette Trouten's disappearance, police went through Robinson's trash at his house. They found a bag of shredded documents, which they then tried to piece back together. One document they were able to reassemble helped them locate a storage locker belonging to John Robinson in Raymore, Missouri. In the meantime, police continued to follow him as he brought women in from all over the U.S. and put them in hotels.

According to Morrison, "the investigators would rent the adjoining room in a hotel when he was having one of his trysts with one of the women."

But authorities also had a contingency plan in place, fearing that he might take one of the women to his property in Linn County and kill her.

"Towards the end of the investigation, we learn that there was a young female that he was trying to lure down to the farm, and that's when we decided that we have enough, and we're not gonna let it go any further," said Dawn Layman, one of the investigators in the case.

After one woman went to police, Robinson, who'd remained married to his wife, Nancy Jo, and also had four children with her by that point, was arrested at the Santa Barbara Estates Mobile Home Park in Olathe, where the couple was living.

In June 2000, he was held on charges of aggravated sexual battery of two out-of-town women he'd met on the Internet as well as taking more than $500 worth of sex toys from one of the women.

Police search John Robinson's farm

Roth, one of the investigators, said that during the police search of Robinson's Kansas farm in June 2000, he was contacted by the handlers of the cadaver dogs. The dogs had smelled a hit around some trash outside of Robinson's trailer. There, police found some barrels.

"As Sgt. Roth was rolling the barrel out, it fell. Then when it fell, a thin line came down the side and you know, it was just a thin red line. And this fly went 'boop' and landed on that red line, and we knew right then and there that that's, that's blood," Brown said.

"Once we looked in there, we saw who we believed was Suzette Trouten," Roth said. "Then the second barrel was all of a sudden very interesting and opened that up. There was a second body in that one and we immediately thought, Izabela Lewicka."

The barrels were loaded into a truck and sent for autopsies. Then, investigators paid a visit to his Missouri storage locker, where they found three barrels. Kitty litter had been put down to mask the smell, Stephen Singular said, and the barrels were in a state of disintegration. Inside each of three barrels, police found women whom, at the time, they had no idea were even missing: Bonner, the prison librarian; and mother-daughter duo, Sheila and Debbie Faith.

Sheila, 45, and Debbie Faith had not been seen or heard from since 1994. Debbie was 15 and had cerebral palsy. She required the use of a wheelchair, police said.

"They have about a little over $1,000 from the government to live on, plus food stamps. They're in pretty desperate straits. John says, 'Come on out here. I'll take care of you. I'll take Debbie.' They pack up. They drive out to the Kansas City area, and he connects her to a post office box in Olathe where her subsidies will come. ... Suddenly they're gone. And nobody really knows where they are, but the checks keep coming in. He will pull $80,000 plus out of that mailbox over the next few years," Stephen Singular said.

The whole house of cards came tumbling down on Robinson at that point.

Roth said John Robinson had sent letters and emails to different family members of all of his victims to delay them from learning the truth about the demise of their loved ones.

"And, in fact, in the Faith and Bonner cases they never contacted the police department," Roth said.

When authorities got search warrants for Robinson's house and office, they found several blank letters with Suzette Trouten's signature at the bottom. The letters looked like what the families had gotten in the mail, Roth said. In his storage locker, they found a photocopy of a Rodeway Inn receipt from 1985 with the name Lisa Stasi on it.

"We realized, 'My gosh. Who, who is this John Robinson? And, who, who else might there be? Who else might there be?'" said Brown, who worked the Robinson investigation.

They also found photocopies of letters that looked like the letters relatives of the missing had received, as if he had a template.

"Everything fell into place. It put everything together at that point," said former detective Layman.

Police connect 4 missing persons to John Robinson

Robinson was charged with the murders of the five women found on his farm and in his storage locker in June 2000.

Police also connected him to four people who had gone missing from Overland Park in the mid-1980s: Godfrey; Clampitt; Stasi; and her daughter, Tiffany Stasi.

In July 2000, Morrison, who prosecuted the case in Kansas’ Johnson County, announced that the existing complaint against Robinson would also include a January 1985 first-degree murder charge in the death of Stasi and aggravated interference with parental custody charge involving the carrying away of baby Tiffany Stasi.

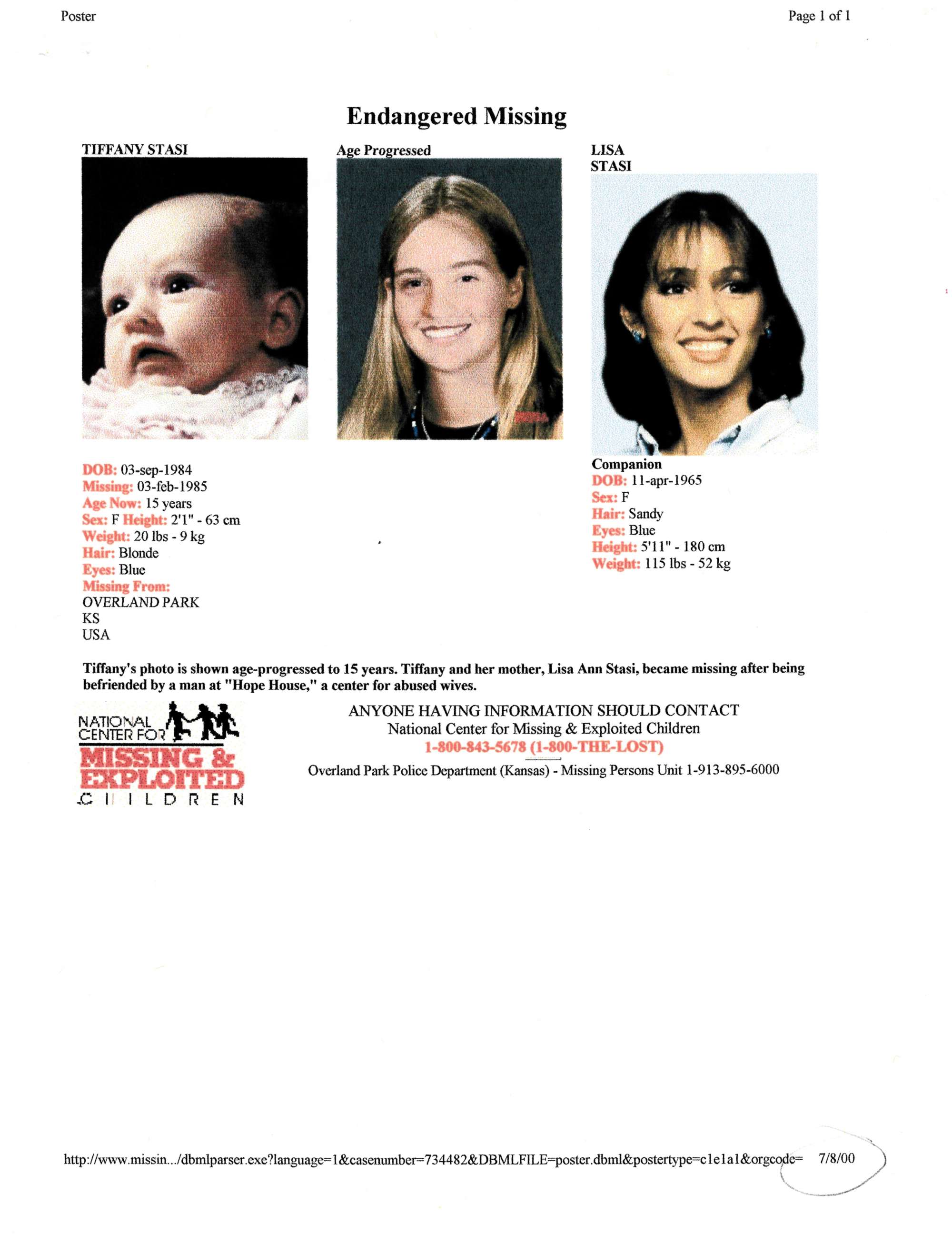

Tiffany Stasi had been adopted by a Midwestern family and was currently living with them, he said. What he didn't tell the public immediately was that the couple who had adopted little Tiffany Stasi was Robinson's brother, Donald Robinson, and his wife.

Roth said that after authorities recovered the bodies at his farm, they received a tip that Donald Robinson and his wife had adopted a child in the 1980s.

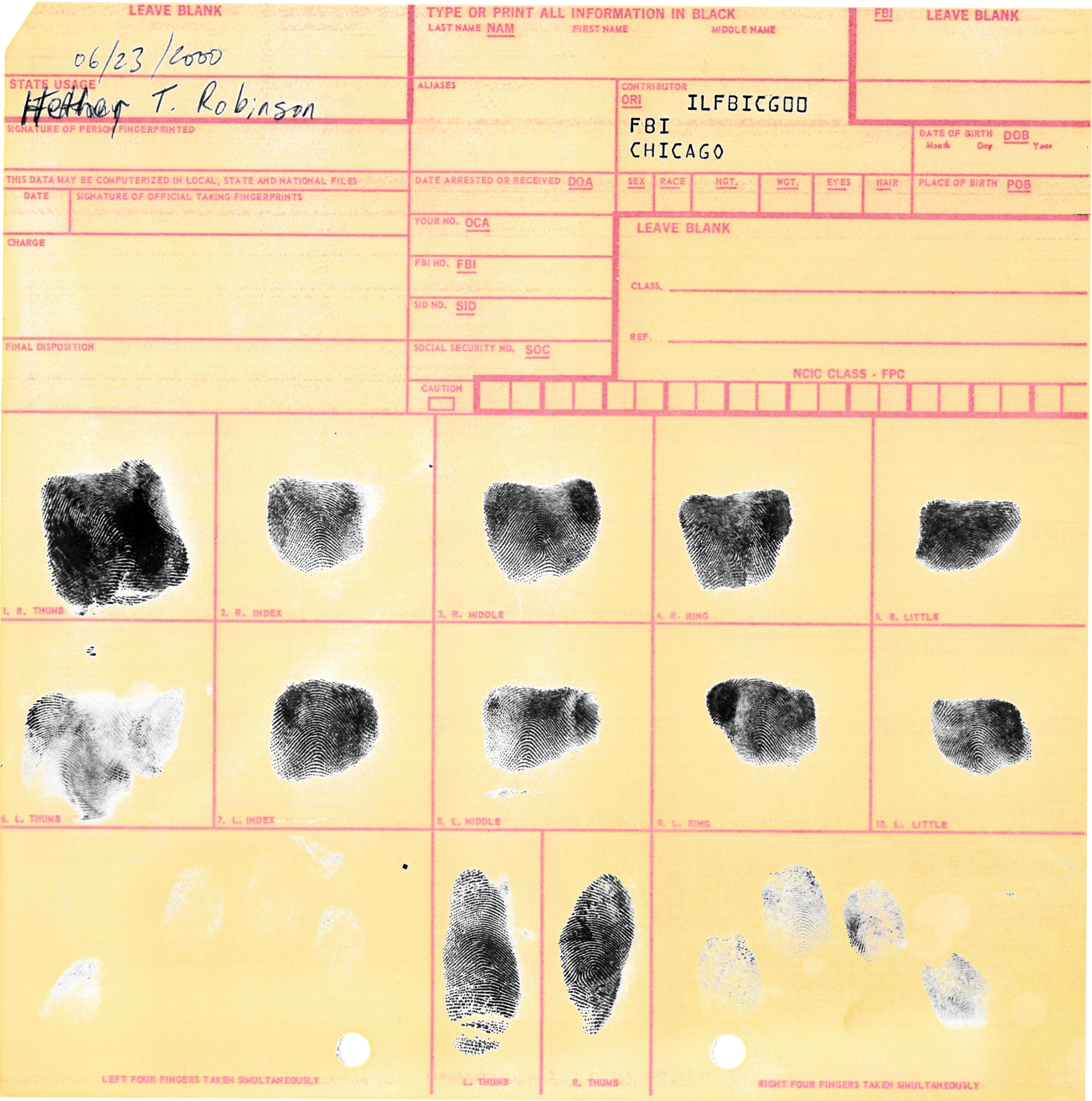

Chicago police went to Donald Robinson's home and spoke to the parents. They took some adoption papers as well and the Robinsons submitted DNA samples, fingerprints and footprints.

"The idea of Tiffany being adopted out to Robinson's brother came as a bombshell to us," Roth said.

Through DNA, authorities confirmed that his 15-year-old adopted daughter, who had been given the name Heather Tiffany Robinson, was, in fact, Tiffany Stasi. They’d initially confirmed her identity by matching her fingerprints and footprints with those from the hospital where she was born.

"What kind of individual would kill a woman and then adopt her baby to a brother?" Brown said. "Heather grows up and John knowing, knowing full well what had happened. What he had done. I don't know. I, I, I certainly can't fathom it."

Morrison said that at first authorities were skeptical about Donald Robinson's role in Tiffany Stasi's abduction but he said that the parents had adoption paperwork that appeared genuine.

Heather Robinson had long known that she'd been adopted but knew nothing about her biological family. She told “20/20” that while she didn't remember her younger years around John Robinson, she did remember the feelings she had when around him.

"He always gave me this really weird, off-putting feeling in the pit of my stomach. It's like walking down a dark alley in the middle of the night while you know someone is behind you, uh, approaching you closer and closer. ... You just felt that dread drop into your stomach," she said.

Donald Robinson and his wife, Frieda, had been trying to have children for at least five years when they started considering adoption. Police said they believe that on a snowy day in January 1985, John Robinson picked up Lisa and Tiffany from Lisa's sister-in-law's home and then drove them back to the Rodeway Inn, where Lisa made that frantic call to her mother-in-law before disappearing.

"Mom [Lisa Stasi] was probably bludgeoned to death literally the day that kid's handed over to Don [Robinson]," Morrison said.

Morrison said that John Robinson had told his brother that it would cost several thousand dollars plus adoption fees and provided what turned out to be fraudulent paperwork, including a certificate of adoption.

As Morrison said at a news conference, "It’s our belief that this adoptive family had no knowledge of any criminal activity relating to the adoption of baby Tiffany. They believed they were the adoptive parents of this little girl but it was not a legal adoption."

"His brother was just another victim of all this," Morrison said.

John Robinson is tried in Kansas

In 2002, John Robinson went on trial in Kansas for Lisa Stasi's murder and the murder of two other women. If convicted, he faced the possibility of a death sentence.

Morrison, who prosecuted the case, said there were more than 23,000 pages of police reports and more than 100 witnesses. Brown, the detective, said authorities recovered about 18 hammers from John Robinson’s property and had then examined at a lab. Technicians were not able to say, however, which hammers were the murder weapons, he said.

"As far as the way John Robinson killed his victims, it was with a hammer. We could tell that from all the autopsies performed on all the bodies that we recovered," Roth said. "As far as why he did it? We really have no idea. On Lisa Stasi, it was for Tiffany, we truly believe that. The Sheila and Debbie Faith, he killed her, or killed them, for their social security checks, to the tune of $97,000. We know on Beverly Bonner, he killed her and cashed all of the alimony checks that had been sent to her. So, there was financial gain. We don't know about the Godfrey and the Clampitt murders. Suzette Trouten, we don't know what happened."

It took the jury less than a day to deliver a guilty verdict on Oct. 29, 2002. John Robinson was sentenced to death in January 2003.

"He was such a con man and he had conned Beverly Bonner when he was in prison in Missouri. We were really afraid if he was just given life that the same thing would happen and that was one of the things that we really discussed about the death penalty," juror Debbie Mahan said.

Because John Robinson had committed crimes in both Kansas and Missouri, he faced criminal charges in both states. After his trial wrapped up in Johnson County, Kansas, the case then had to be handled in Missouri.

In Missouri, authorities offered him a deal where if he pleaded guilty to the five murders, he would avoid a death sentence.

In exchange for not getting the death sentence, there was hope that Robinson would reveal the location of the remains of the three women who had not yet been found, including Lisa Stasi. He was given the plea deal but he gave no information in exchange.

He is now 75 and on death row in Kansas. He is appealing his death sentence.