"Let It Fall: Los Angeles 1982-1992"

"Let It Fall: Los Angeles 1982-1992" is a documentary film looking back 25 years at what transpired before and after the Rodney King verdict.

By MELIA PATRIA AND ENJOLI FRANCIS

"Let It Fall: Los Angeles 1982-1992" is directed by John Ridley and produced by ABC News' Lincoln Square Productions.

"Let It Fall" takes an unflinching look at the 1992 Los Angeles uprising, tracing its roots back a decade and unfolding its history as a series of very personal decisions and very public failures.

The film weaves heartbreaking firsthand accounts from Angelinos of different backgrounds and classes, caught up in a cascade of rising tension, culminating in an explosion of anger and fear after the Rodney King verdict.

"Let It Fall: Los Angeles 1982-1992" is directed by John Ridley and produced by ABC News' Lincoln Square Productions.

"Let It Fall" takes an unflinching look at the 1992 Los Angeles uprising, tracing its roots back a decade and unfolding its history as a series of very personal decisions and very public failures.

The film weaves heartbreaking firsthand accounts from Angelinos of different backgrounds and classes, caught up in a cascade of rising tension, culminating in an explosion of anger and fear after the Rodney King verdict.

The two-hour ABC News documentary "Let It Fall: LA 1982-1992" will air on ABC to mark the 25th anniversary of the Rodney King verdict.

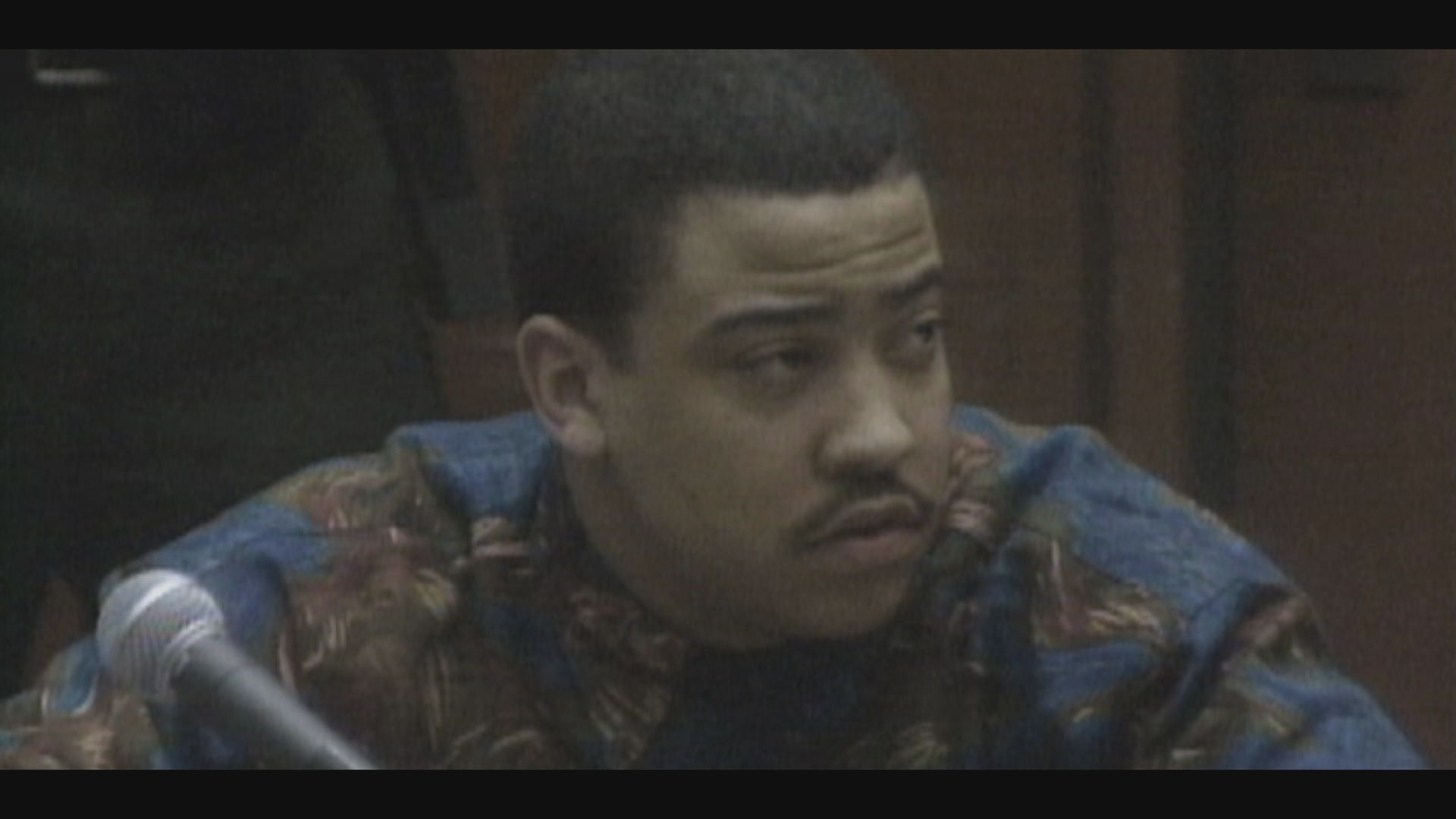

'L.A. FOUR' DAMIAN WILLIAMS

Damian "Football" Williams was 18 years old on April 29, 1992, when he participated in a series of attacks on motorists at the intersection of Florence and Normandie in South Central Los Angeles, following the acquittals of four white police officers in the Rodney King beating trial.

The notorious attack on truck driver Reginald Denny and other assaults were videotaped and broadcasted on live television and quickly came to symbolize the violence of the riots. The group of young black men who were charged became known as the "L.A. Four" and Williams, who was accused of throwing a brick at Denny's head, was considered the most high-profile member.

Williams was eventually sentenced to a maximum 10 years in prison for the attack on Denny and four other people. He was released after four years, and went back to prison in 2003 for his role in a murder unrelated to the 1992 social unrest.

From Calipatria State Prison, Williams gave a rare interview to John Ridley for the documentary "Let It Fall." The following are excerpts, in his own words.

BEATING OF REGINALD DENNY

The only image that they had of me for 25 years, I’ve been quiet. I haven’t spoken to nobody about this incident- about what occurred. So, if I had to just look at it for what it is and never heard any reports after the fact, I would think he’s somebody that was evil. Somebody that didn’t have no sense of feelings or emotions or didn’t care for nothing. Because of that image. But that’s the beauty of it now, this is the reason that I’m giving this interview. So I could shed a new light on myself and know that who I was when I was 18- I’m not that person now. And there’s a great saying that I live by- “It ain’t how you started, it’s how you finish what matters most.” And I’m starting to finish on a good note.

So when I do leave this world, what people do speak about me, they speak about the good that I contributed, not the bad things that I got caught up in as an adolescent in South Central.

I never had anger with white kids at different schools, schools that I went to, so I didn’t have anger because as a kid at the time, I didn’t know what anger was because I had always been sheltered. I’d been with my mother all my life and my mother had worked with white people as a nurse- some of the most nice and compassionate people. But everybody is not the same.

Reginald Denny, to see face-to-face, I would talk to him and I would let him know how I feel from my heart. But, we must understand that I must speak to the person about how I feel and what I think now. The thing is, he is the one that suffered, his family suffered, for what took place over there.

So my thing is, I would want to talk to him and not the world, because the world don’t need to know about how I feel when it comes to this, but Denny needs to know it.

MORE: 'LET IT FALL': 'L.A. FOUR' MEMBER SHARES LIFE LESSONS, 25 YEARS AFTER RIOTS

'L.A. FOUR' DAMIAN WILLIAMS

Damian "Football" Williams was 18 years old on April 29, 1992, when he participated in a series of attacks on motorists at the intersection of Florence and Normandie in South Central Los Angeles, following the acquittals of four white police officers in the Rodney King beating trial.

The notorious attack on truck driver Reginald Denny and other assaults were videotaped and broadcasted on live television and quickly came to symbolize the violence of the riots. The group of young black men who were charged became known as the "L.A. Four" and Williams, who was accused of throwing a brick at Denny's head, was considered the most high-profile member.

Williams was eventually sentenced to a maximum 10 years in prison for the attack on Denny and four other people. He was released after four years, and went back to prison in 2003 for his role in a murder unrelated to the 1992 social unrest.

From Calipatria State Prison, Williams gave a rare interview to John Ridley for the documentary "Let It Fall." The following are excerpts, in his own words.

BEATING OF REGINALD DENNY

The only image that they had of me for 25 years, I’ve been quiet. I haven’t spoken to nobody about this incident- about what occurred. So, if I had to just look at it for what it is and never heard any reports after the fact, I would think he’s somebody that was evil. Somebody that didn’t have no sense of feelings or emotions or didn’t care for nothing. Because of that image. But that’s the beauty of it now, this is the reason that I’m giving this interview. So I could shed a new light on myself and know that who I was when I was 18- I’m not that person now. And there’s a great saying that I live by- “It ain’t how you started, it’s how you finish what matters most.” And I’m starting to finish on a good note.

So when I do leave this world, what people do speak about me, they speak about the good that I contributed, not the bad things that I got caught up in as an adolescent in South Central.

I never had anger with white kids at different schools, schools that I went to, so I didn’t have anger because as a kid at the time, I didn’t know what anger was because I had always been sheltered. I’d been with my mother all my life and my mother had worked with white people as a nurse- some of the most nice and compassionate people. But everybody is not the same.

Reginald Denny, to see face-to-face, I would talk to him and I would let him know how I feel from my heart. But, we must understand that I must speak to the person about how I feel and what I think now. The thing is, he is the one that suffered, his family suffered, for what took place over there.

So my thing is, I would want to talk to him and not the world, because the world don’t need to know about how I feel when it comes to this, but Denny needs to know it.

MORE: 'LET IT FALL': 'L.A. FOUR' MEMBER SHARES LIFE LESSONS, 25 YEARS AFTER RIOTS

In March 1991, Rodney King led California Highway Patrol officers on a high-speed chase. Once stopped, he was pulled from the car and several officers beat him with their batons. A year later, the trial concluded and a jury acquitted the officers. Hours later, protests and riots erupted across Los Angeles.

LAPD OFFICER LISA PHILLIPS

In 1989, the year Lisa Phillips got her badge, she was one of only a handful of women in her graduating class with the Los Angeles Police Department.

Phillips said that back then, she was living two lives: one, as openly gay; and the other, as a police officer who shared little to nothing of her personal life.

In April 1992, the 33-year-old Phillips was assigned to the 77th division in South Central, Los Angeles, and was on foot patrol with her partner when riots broke out following the acquittals of four white police officers in the Rodney King beating trial. Disobeying retreat orders, they entered the fray to rescue an Asian woman from a brutal attack.

In an interview for the documentary "Let It Fall,” Phillips shared her memories from 1992, and discussed her personal journey and experiences as a female officer. Below are excerpts.

THE RESCUE

My best memory is—“AWD in progress. 51st and Normandie. Asian women being beaten to death in her car or assaulted in her car by a mob of 20 people.” Something like that. The call came out and it sort of hung there in the air with all the other calls. And we just said, 'Man, we can't-- we gotta go.”

And then we said, 'Well, what are the repercussions if we don't go? Somebody might die. We-- we gotta go.' [My partner’s] like, “Okay, we gotta go. You're driving.” And off we went. And we turned around -- one of us said, “I know we're gonna get in trouble for this.” And we said, “Well, whatever.'..."

As we got to Florence and Normandie the liquor store was on fire… We're getting attacked and surrounded with rocks, and bottles, and people. And there's hundreds of people. We're looking for our victim.

But I thought as we're driving there, “Man, I don't know. I don't know if we're gonna make it. It's just us. There's no other cops around.” My partner says, “I want you to call my wife if I get killed because you're my partner. I don't want somebody that she doesn't know to come knocking on the door.” I go, “All right. I'll call your wife.” And I thought, “I've got a lover, you know, at home. And nobody knows that she exists. Who's gonna tell her what if — who's gonna call my mom or my girlfriend?” I said, “Partner, look, I'm gay. You probably figured it out. But I'm coming out to you. I've got-- a lover' ”will you call her if something happens to me?' And-- he said, “Don't worry.” He said, “Partner, I got your back.” I said, “All right, I love you. Let's go.”

There was, like, 20 guys. And they scattered. Except one guy… One guy was leaning in the driver side and he had this woman by the collar. And he was beating the sh-t out of her. Punch-- punching her.

She was still seat belted in. She was bloody, unconscious. We thought she was dead….At that point I said, “We gotta get out of this car” Now we're being attacked now. We've got rocks and bottles coming at us. The glass is all in the street. I remember stepping out of the car and hearing the glass crunch under my boots.

He's running back to the car with this woman in his arms. We're being attacked, yelled at, screamed at. A rock or a bottle or something hits him in the back and he goes down in the street-- knocks him down. The woman rolls-- flies out of his arms into all this glass. I'll never forget when he fell. The crowd laughed. I'll never forget that my whole life. “OH, stupid f---kin' -- you know, whatever they were saying “pigs”. And I always thought to myself, “This is man's inhumanity to man right here. This is just-- this is what it's all about. This is the worst of the worst.” So I thought the woman was dead. I go to my partner—“Get up. Get up. Get up.” And he got up. We ran back up to the woman. He picked up an arm and a leg, I picked up an arm and a leg. And there's nowhere for the car to go. We don't have an exit. We don't have an escape route. There's nowhere to go.

My partner's eyes locked with somebody's in the crowd. I'm not sure how it all happened. But some people stepped aside and created a space big enough to let our car go through. It was either-- a beautiful thing or a self-preservation thing. I prefer to believe that it was-- it's something in their soul that they said, “We gotta let these people go.” And we got her into a room in the emergency room. And she came to and we realized, “Oh, thank goodness. She's not dead.”

MORE: 'LET IT FALL': OFFICER LISA PHILLIPS, IN HER OWN WORDS

LAPD OFFICER LISA PHILLIPS

In 1989, the year Lisa Phillips got her badge, she was one of only a handful of women in her graduating class with the Los Angeles Police Department.

Phillips said that back then, she was living two lives: one, as openly gay; and the other, as a police officer who shared little to nothing of her personal life.

In April 1992, the 33-year-old Phillips was assigned to the 77th division in South Central, Los Angeles, and was on foot patrol with her partner when riots broke out following the acquittals of four white police officers in the Rodney King beating trial. Disobeying retreat orders, they entered the fray to rescue an Asian woman from a brutal attack.

In an interview for the documentary "Let It Fall,” Phillips shared her memories from 1992, and discussed her personal journey and experiences as a female officer. Below are excerpts.

THE RESCUE

My best memory is—“AWD in progress. 51st and Normandie. Asian women being beaten to death in her car or assaulted in her car by a mob of 20 people.” Something like that. The call came out and it sort of hung there in the air with all the other calls. And we just said, 'Man, we can't-- we gotta go.”

And then we said, 'Well, what are the repercussions if we don't go? Somebody might die. We-- we gotta go.' [My partner’s] like, “Okay, we gotta go. You're driving.” And off we went. And we turned around -- one of us said, “I know we're gonna get in trouble for this.” And we said, “Well, whatever.'..."

As we got to Florence and Normandie the liquor store was on fire… We're getting attacked and surrounded with rocks, and bottles, and people. And there's hundreds of people. We're looking for our victim.

But I thought as we're driving there, “Man, I don't know. I don't know if we're gonna make it. It's just us. There's no other cops around.” My partner says, “I want you to call my wife if I get killed because you're my partner. I don't want somebody that she doesn't know to come knocking on the door.” I go, “All right. I'll call your wife.” And I thought, “I've got a lover, you know, at home. And nobody knows that she exists. Who's gonna tell her what if — who's gonna call my mom or my girlfriend?” I said, “Partner, look, I'm gay. You probably figured it out. But I'm coming out to you. I've got-- a lover' ”will you call her if something happens to me?' And-- he said, “Don't worry.” He said, “Partner, I got your back.” I said, “All right, I love you. Let's go.”

There was, like, 20 guys. And they scattered. Except one guy… One guy was leaning in the driver side and he had this woman by the collar. And he was beating the sh-t out of her. Punch-- punching her.

She was still seat belted in. She was bloody, unconscious. We thought she was dead….At that point I said, “We gotta get out of this car” Now we're being attacked now. We've got rocks and bottles coming at us. The glass is all in the street. I remember stepping out of the car and hearing the glass crunch under my boots.

He's running back to the car with this woman in his arms. We're being attacked, yelled at, screamed at. A rock or a bottle or something hits him in the back and he goes down in the street-- knocks him down. The woman rolls-- flies out of his arms into all this glass. I'll never forget when he fell. The crowd laughed. I'll never forget that my whole life. “OH, stupid f---kin' -- you know, whatever they were saying “pigs”. And I always thought to myself, “This is man's inhumanity to man right here. This is just-- this is what it's all about. This is the worst of the worst.” So I thought the woman was dead. I go to my partner—“Get up. Get up. Get up.” And he got up. We ran back up to the woman. He picked up an arm and a leg, I picked up an arm and a leg. And there's nowhere for the car to go. We don't have an exit. We don't have an escape route. There's nowhere to go.

My partner's eyes locked with somebody's in the crowd. I'm not sure how it all happened. But some people stepped aside and created a space big enough to let our car go through. It was either-- a beautiful thing or a self-preservation thing. I prefer to believe that it was-- it's something in their soul that they said, “We gotta let these people go.” And we got her into a room in the emergency room. And she came to and we realized, “Oh, thank goodness. She's not dead.”

MORE: 'LET IT FALL': OFFICER LISA PHILLIPS, IN HER OWN WORDS

They spoke emotionally about race, the police, and the uprising in the documentary "Let It Fall: Los Angeles 1982-1992."

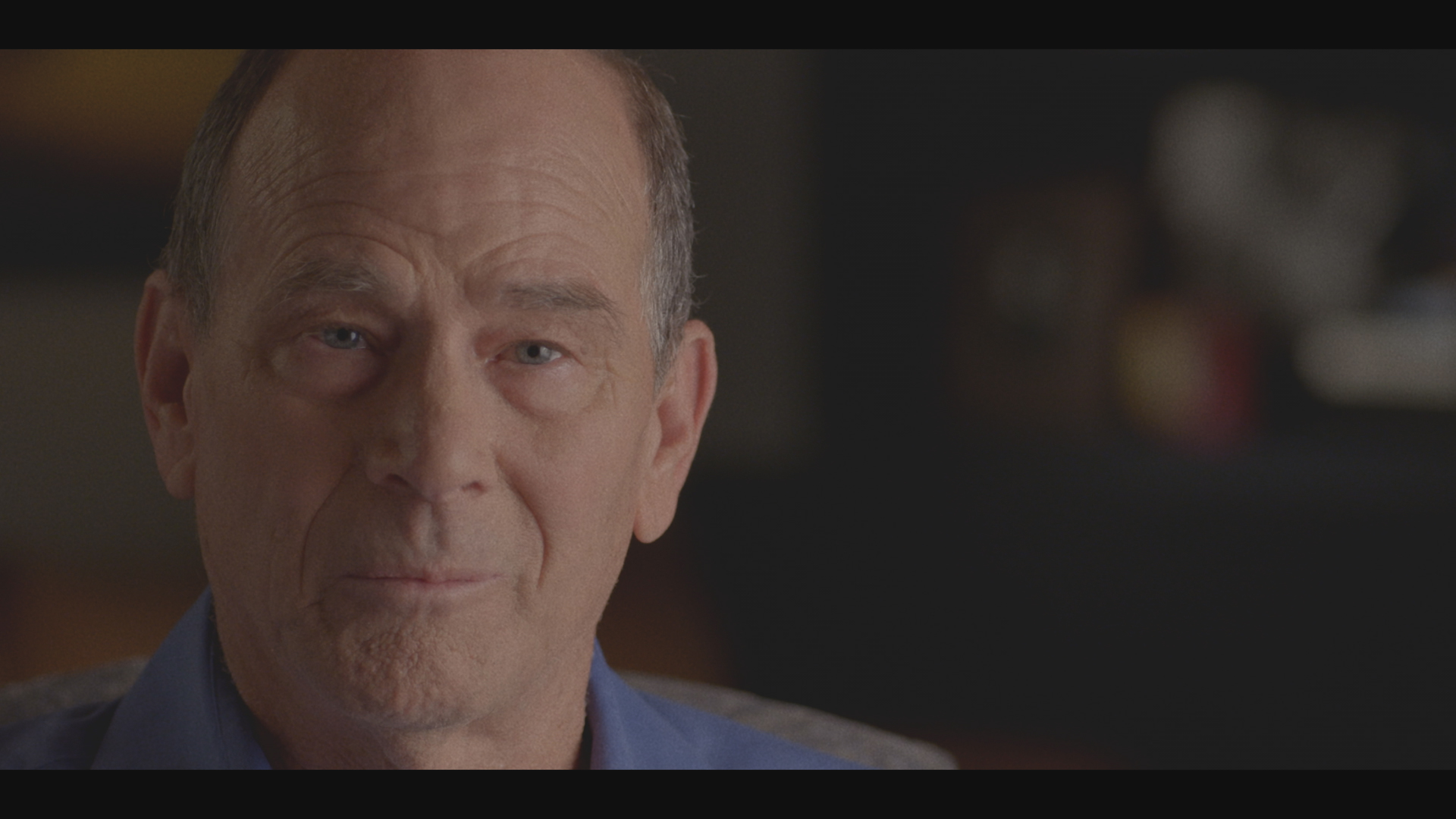

RODNEY KING JUROR HENRY KING

Henry King was Juror No. 8 in the controversial and highly-publicized state trial against four white police officers charged in the beating of Rodney King.

On April 29, 1992, the police officers were acquitted by what was widely reported as an "all-white jury." King, a retired lineman splicer for Southern California Edison, said he told no one at the time that he was actually mixed race. His mother is a white woman from Arkansas; his father, was a black man who served in the military.

In 2012, at age 69, King decided to embrace his racial identity.

During an interview for the documentary "Let It Fall," King, now 74, discussed his personal journey as a bi-racial individual and why it was important to him to go public with his story. The following are excerpts in his own words.

WHY GO PUBLIC

On the Rodney King beating trial…I didn't tell anybody. I just was, you know, Mr. White Guy. And nobody knew. Nobody knows now unless they see this [documentary].

I wanted the people to know that it wasn't an ‘all-white jury’. We had a Filipino, we had a Hispanic, and [we] had me. And my father was black. And my mother's white.

I guess it was a time in my life that I said, 'I'm proud of my family, both sides.' And I wanted people to know that I had a black family. And they're very, very intelligent people. One of my cousins was the head of the FCC. And I have other cousins that have prominent places in society. I was proud of them, of their accomplishments. And the cousin that was the head of the FCC, he's now an ambassador.

I think there's a lot of people that are, of mixed race. And, I think by me coming out and, you know, talkin' about my background, my family, maybe it'll just touch somebody else. To know they're not alone.

MORE: 'LET IT FALL': RODNEY KING JUROR, IN HIS OWN WORDS

RODNEY KING JUROR HENRY KING

Henry King was Juror No. 8 in the controversial and highly-publicized state trial against four white police officers charged in the beating of Rodney King.

On April 29, 1992, the police officers were acquitted by what was widely reported as an "all-white jury." King, a retired lineman splicer for Southern California Edison, said he told no one at the time that he was actually mixed race. His mother is a white woman from Arkansas; his father, was a black man who served in the military.

In 2012, at age 69, King decided to embrace his racial identity.

During an interview for the documentary "Let It Fall," King, now 74, discussed his personal journey as a bi-racial individual and why it was important to him to go public with his story. The following are excerpts in his own words.

WHY GO PUBLIC

On the Rodney King beating trial…I didn't tell anybody. I just was, you know, Mr. White Guy. And nobody knew. Nobody knows now unless they see this [documentary].

I wanted the people to know that it wasn't an ‘all-white jury’. We had a Filipino, we had a Hispanic, and [we] had me. And my father was black. And my mother's white.

I guess it was a time in my life that I said, 'I'm proud of my family, both sides.' And I wanted people to know that I had a black family. And they're very, very intelligent people. One of my cousins was the head of the FCC. And I have other cousins that have prominent places in society. I was proud of them, of their accomplishments. And the cousin that was the head of the FCC, he's now an ambassador.

I think there's a lot of people that are, of mixed race. And, I think by me coming out and, you know, talkin' about my background, my family, maybe it'll just touch somebody else. To know they're not alone.

MORE: 'LET IT FALL': RODNEY KING JUROR, IN HIS OWN WORDS

On April 29, 1992, police were ordered to retreat from 71st Street & Normandie Avenue where tensions were running high. They did not return for hours as looting, arson, and assaults took place at the nearby intersection of Florence & Normandie.

JUNG HUI LEE, WHO LOST HER SON IN THE RIOTS

Jung Hui Lee and her husband emigrated from Korea to the United States in 1972, settling first in Virginia and later in California in pursuit of the “American Dream”. They raised a family in Los Angeles and for many years worked multiple low-wage jobs to provide for their children.

During the 1992 L.A. uprising, Lee’s 18-year old son, Edward Jae Song Lee entered the fray to help protect his Koreatown neighborhood, which was virtually abandoned by police. On April 30, 1992 Edward was fatally shot by crossfire. Later, it was discovered he was shot by another Korean-American by mistake.

Days after Lee’s death, thousands of people assembled in Koreatown to march for peace. In all, over 300 businesses were burned and looted in the district, with damage exceeding $200 million. Many uninsured businesses never re-opened, uprooting the lives of Korean-American families who had labored for years to build their livelihoods from scratch.

In memory of the losses suffered in 1992, Korean-Americans call the unrest "Sa-I-Gu," or 4-2-9 in native pronunciation. It is remembered by many Korean-Americans as an awakening to their minority status, a time they felt abandoned by the government and unfairly portrayed by the media as aggressors despite inadequate law enforcement protection.

Lee spoke to John Ridley in an interview for the documentary "Let It Fall: Los Angeles 1982-1992.” The following are excerpts.

RIOTS ON TV

On television, they would visually focus on fires and looting… And the broadcasters, though it was not a conflict between Koreans and blacks, they began to add those elements little by little. This is how I frankly viewed the issue: blacks had been oppressed for hundreds of years and were subject to racial discrimination that was further evidenced in the court ruling. But how the broadcasters continued to put Koreatown into focus and made an issue out of it, both puzzled and enraged us. There, we were faced with a discrimination of language. That’s what I thought. So we said amongst ourselves that this shouldn’t be. But our voice was so faint because the Korean community was very small. And the broadcasters painted it as a conflict between Koreans and blacks and made it big, in my opinion.

That day, I only watched the television and felt ill at ease, but still thought that it would never come to my house. The route that the black rioters took was wide roads like Western and Vermont, and it kept getting closer to our home… my son went out despite my dissuading him from getting involved. My son got sucked into the war.

Because though he was born here, he experienced the difficult times when he was young, when we had brought him to our workplaces in our struggling days. We had brought him to the swap meet, and he helped us, so he knows. So he thought all that we had amassed, although not a lot, was about to disappear. So he was very enraged and convinced that he had to go out and combat. Or if not, help at least.

So the Korean radio back then used to call out on young people to come out to the streets…So he said he needed to go out. And I said, “No, you can’t. You need to protect us.” And we had an arguments saying, “You can’t go out.”…

I wanted to go out, too, honestly. I am also the type to get enraged by that kind of things. But I couldn’t say, “I also want to go out with you, son.” It’s just how I secretly felt. … When the radio broadcasted that battle story, my son asked about it and I explained. Then he said, “This is it!” “Let’s go out, mother, and throw at least one stone and stop this….The radio broadcast seemed to be firmly convinced in stating that the blacks were invading in, that the blacks were targeting Koreans, and that it was a conflict between Koreans and blacks.. I felt that black people were reacting to a conflict with white people by attacking Koreans. And I thought “How could they be so reckless?” “Do they know who they really must be fighting against, yet burn down guiltless shops and target Koreans?”… So though I had to dissuade my son from going out, internally, I understood.

That day, around 10 o’clock, around then, a woman called Radio Korea. I heard this story myself. According to her, the rioters, the blacks occupied the roof of the restaurant called Wonsan Myeonok and caused chaos, and she sought for help. Then Radio Korea without verifying, well there was no such verification process then, they just had to believe incoming reports. It was an emergency situation to learn of the rioters being up there. So they had live broadcast soliciting help for that. But never in my dream, had I ever imagined that my son would go there.

Even before I saw the papers, the radio had announced that there had been a Korean victim. So when I connected the dots, I came to learn of the place, and that the young man on the paper was my son.

My son was shot by someone who had fired from the roof, and it turned out that the people on the roof weren’t blacks, but Koreans.

MORE: 'LET IT FALL': JUNG HUI LEE, IN HER OWN WORDS

JUNG HUI LEE, WHO LOST HER SON IN THE RIOTS

Jung Hui Lee and her husband emigrated from Korea to the United States in 1972, settling first in Virginia and later in California in pursuit of the “American Dream”. They raised a family in Los Angeles and for many years worked multiple low-wage jobs to provide for their children.

During the 1992 L.A. uprising, Lee’s 18-year old son, Edward Jae Song Lee entered the fray to help protect his Koreatown neighborhood, which was virtually abandoned by police. On April 30, 1992 Edward was fatally shot by crossfire. Later, it was discovered he was shot by another Korean-American by mistake.

Days after Lee’s death, thousands of people assembled in Koreatown to march for peace. In all, over 300 businesses were burned and looted in the district, with damage exceeding $200 million. Many uninsured businesses never re-opened, uprooting the lives of Korean-American families who had labored for years to build their livelihoods from scratch.

In memory of the losses suffered in 1992, Korean-Americans call the unrest "Sa-I-Gu," or 4-2-9 in native pronunciation. It is remembered by many Korean-Americans as an awakening to their minority status, a time they felt abandoned by the government and unfairly portrayed by the media as aggressors despite inadequate law enforcement protection.

Lee spoke to John Ridley in an interview for the documentary "Let It Fall: Los Angeles 1982-1992.” The following are excerpts.

RIOTS ON TV

On television, they would visually focus on fires and looting… And the broadcasters, though it was not a conflict between Koreans and blacks, they began to add those elements little by little. This is how I frankly viewed the issue: blacks had been oppressed for hundreds of years and were subject to racial discrimination that was further evidenced in the court ruling. But how the broadcasters continued to put Koreatown into focus and made an issue out of it, both puzzled and enraged us. There, we were faced with a discrimination of language. That’s what I thought. So we said amongst ourselves that this shouldn’t be. But our voice was so faint because the Korean community was very small. And the broadcasters painted it as a conflict between Koreans and blacks and made it big, in my opinion.

That day, I only watched the television and felt ill at ease, but still thought that it would never come to my house. The route that the black rioters took was wide roads like Western and Vermont, and it kept getting closer to our home… my son went out despite my dissuading him from getting involved. My son got sucked into the war.

Because though he was born here, he experienced the difficult times when he was young, when we had brought him to our workplaces in our struggling days. We had brought him to the swap meet, and he helped us, so he knows. So he thought all that we had amassed, although not a lot, was about to disappear. So he was very enraged and convinced that he had to go out and combat. Or if not, help at least.

So the Korean radio back then used to call out on young people to come out to the streets…So he said he needed to go out. And I said, “No, you can’t. You need to protect us.” And we had an arguments saying, “You can’t go out.”…

I wanted to go out, too, honestly. I am also the type to get enraged by that kind of things. But I couldn’t say, “I also want to go out with you, son.” It’s just how I secretly felt. … When the radio broadcasted that battle story, my son asked about it and I explained. Then he said, “This is it!” “Let’s go out, mother, and throw at least one stone and stop this….The radio broadcast seemed to be firmly convinced in stating that the blacks were invading in, that the blacks were targeting Koreans, and that it was a conflict between Koreans and blacks.. I felt that black people were reacting to a conflict with white people by attacking Koreans. And I thought “How could they be so reckless?” “Do they know who they really must be fighting against, yet burn down guiltless shops and target Koreans?”… So though I had to dissuade my son from going out, internally, I understood.

That day, around 10 o’clock, around then, a woman called Radio Korea. I heard this story myself. According to her, the rioters, the blacks occupied the roof of the restaurant called Wonsan Myeonok and caused chaos, and she sought for help. Then Radio Korea without verifying, well there was no such verification process then, they just had to believe incoming reports. It was an emergency situation to learn of the rioters being up there. So they had live broadcast soliciting help for that. But never in my dream, had I ever imagined that my son would go there.

Even before I saw the papers, the radio had announced that there had been a Korean victim. So when I connected the dots, I came to learn of the place, and that the young man on the paper was my son.

My son was shot by someone who had fired from the roof, and it turned out that the people on the roof weren’t blacks, but Koreans.

MORE: 'LET IT FALL': JUNG HUI LEE, IN HER OWN WORDS

They shared their thoughts with the team behind the documentary "Let It Fall: Los Angeles 1982-1992."