One Nation, Overdosed: Snapshots of Americans struggling under the opioid crisis

"Nightline" and ABC affiliates report on the epidemic that kills at least 91 Americans every day

By PIERRE THOMAS, ASHLEY LOUSZKO, DURRELL DAWSON, ERIN BRADY, GENEVA SANDS, ASHAN SINGH and LAUREN EFFRON

A 22-year-old mother in Kentucky who had a little girl. A fifth grader in Miami who had just left a swimming pool. A police officer in Ohio who nearly died during an arrest.

These are just a handful of victims who have suffered fatal or near-fatal opioid overdoses this summer out of the tens of thousands of Americans who grapple with opioid addiction every day.

Opioids are a class of drugs that include the illegal drug heroin and powerful pain relievers available legally with a prescription, such as oxycodone, codeine and morphine, according to the National Institute on Drug Abuse.

The Centers for Disease Control say overdose deaths involving prescription opioids have quadrupled since 1999 and drug overdoses now kill more people every year than gun violence or car accidents.

"One American now dies of a drug overdose every 11 minutes and more than two million Americans are addicted to prescription painkillers," U.S. Attorney General Jeff Sessions said on July 20.

To take an in-depth look at the scope of the opioid epidemic, "Nightline" monitored fatal and near-fatal overdose cases for just one week in July.

Communities across the nation are trying to figure out new ways to pull the country out of this epidemic, from a program in Albuquerque, New Mexico, called "Addict to Athlete" to a family treatment drug court in Erie County, New York, that offers mental health counseling and access to a relapse center.

But health care officials point out that the most recent national report on the total number of opioid overdose deaths, put out by the CDC, is already two years old. There is such a lag in information gathering that many in the public health community have been calling for a national database of real-time tracking known as "syndromic surveillance."

Resources for Heroin and Opioid Addiction, Treatment and Support

The complicated task of tracking opioid overdoses

The most up-to-date national total of opioid overdose deaths comes from 2015, and complete data from 2016 isn't expected to be available until the end of this year. It takes a significant amount of time for data on the local level to bubble up and be analyzed nationally by the CDC.

By the time the CDC corrects for regional differences in how reports are confirmed, collected and defined, more than a year can pass.

In 2015, more than 33,000 Americans died from opioid overdoses, according to the CDC, which says preliminary data from 2016 suggests the total number of overdose deaths will increase.

Daniel Ciccarone, an associate editor for the International Journal of Drug Policy and professor at the University of California San Francisco School of Medicine, said the lag time of a year is an improvement from how data was collected a few years ago, but it’s still a problem for understanding the scope of the current epidemic.

"The numbers are extraordinary and it's easy to get kind of numbed when you're in that kind of event when you say, 'well, this has had more deaths than the Vietnam War, this has had more deaths in a given year than HIV-AIDS,'" Ciccarone said. "We're reached epidemic levels because this is of crisis proportions. It's going to require a crisis response: resources, time, effort, humanity, compassion of a historic proportion."

"Nightline" reached out to officials in all 50 states and the District of Columbia to determine how each track both fatal and non-fatal overdoses. Each state uses its own criteria to collect data and even the way one state defines an opioid overdose can differ from another. Most states are reluctant to label a death as an opioid overdose until it is confirmed by toxicology reports and the time each local district takes to finalize an individual death certificate can range anywhere from days to months.

There is also variation in terms of non-fatal opioid overdoses. The most current analysis of national hospital data by the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality shows 1.27 million emergency room visits or inpatient stays were for non-fatal overdoses in 2014 – the most recent year the data is available. Often, victims that don't end up in hospitals or morgues return to their lives without the overdose being documented. Few states conduct real-time monitoring of non-fatal overdoses from sources like hospital emergency departments and EMS reports.

Twenty states, Washington, D.C., and various hospital associations agreed to share with "Nightline" preliminary overdose data from the seven days covering July 17 through July 23. The results provide a patchwork of data that highlights the difficulty of rapidly tracking the victims of the opioid crisis. Each state that shared their info cautioned that their numbers would not represent the full scope of those who overdosed during our seven-day report.

WATCH PART 1 OF OUR REPORT:

WATCH PART 2 OF OUR REPORT:

"Nightline's" findings in tracking opioid overdoses across the country

"Nightline" found that public health departments and hospital associations in all 50 states collect opioid overdose data in vastly different ways. Some health care systems have to wait months after a person has died for toxicology reports to confirm an opioid contributed to the death. Other systems don't even track overdose visits to emergency rooms or calls to first responders.

After Arizona's Gov. Doug Ducey declared a state of emergency in June, state and local agencies there began working together to more quickly track suspected opioid overdoses. The state posts its opioid overdose data on a weekly basis. For the seven-day period "Nightline" tracked, there were 174 suspected opioid overdoses recorded. Of that number, 22 were fatal.

In Illinois, the state's Department of Public Health was able to provide hospital emergency department data that showed 273 opioid overdose visits during "Nightline's" seven-day timeline. This figure accounted for only 0.26 percent of total visits to Illinois hospitals, according to the state.

In New Jersey, the state's Department of Health was able to collect data from both hospital emergency department data (97 visits) and EMS reports (172 reports) over the seven days for "Nightline." But New Jersey State Police track overdose reports separately.

There is increasing recognition that real-time data can help communities respond to overdose outbreaks by stocking up on the opioid-reversing drug naloxone, commonly referred to by the brand name Narcan, and tracking the people selling illicit drugs. On day one of "Nightline's" seven-day report, the CDC announced $12 million in funding to 23 states and Washington, D.C., to better track opioid-related overdoses.

The National Institute on Drug Abuse's HIDTA (High Intensity Drug Trafficking Areas) program launched an overdose reporting application this January that is currently in use across 11 states and 38 counties. Called ODMap, the app allows first responders to quickly submit details about an overdose so it can be analyzed to detect trends.

"Even if it's only one person, one person can save one life, by entering data and maybe foreseeing something that might happen down the road. That makes it all worthwhile," Captain Richard Flynn of the Arlington, Massachusetts, police department told ABC affiliate WCVB.

The app was developed by the Washington/Baltimore HIDTA over the past year and continues to be rolled out in counties across the country. Since ODMap's pilot phase, over 3,000 overdoses have been reported by first responders using the app. It is this type of reporting on the local level that will ultimately provide the most accurate national picture.

Snohomish Health District in Washington state, which covers public health services in Snohomish County, worked with its local fire, police, EMS, hospitals and clinics to gather data for "Nightline" and shows 37 suspected opioid overdoses occurred during our seven-day period. Three of those overdoses resulted in death.

Some cities like Cincinnati have started posting real-time data that allows the public to pinpoint instances of heroin overdoses to specific hours and neighborhoods.

"I think it's really about building a community of how we can address this epidemic," Cincinnati Chief Data Officer Brandon Crowley told ABC affiliate WCPO. "Because it's not just Cincinnati, it's not just affecting Ohio. It's affecting the country."

American life under the opioid crisis

"Nightline" partnered with ABC affiliate stations across the country for this report, covering the opioid crisis in their communities and nationally from July 17 to July 23, and the following stories are just some snapshots from the lives of Americans affected by this epidemic.

This map illustrates our ABC affiliates' coverage of the opioid epidemic during the week of July 17 to 23:

These stories highlight those who overdosed, the families members left behind to pick up the pieces, the health care personnel trying to save lives, the law enforcement officers chasing down drug dealers, and city and state officials pushing legislation and funding to help combat the deadliest drug crisis in American history.

It was just after sunrise in this manufacturing town when a man called 911.

"He was ingesting what he thought was cocaine," said Lawrence Police Chief James Fitzpatrick.

But testing later showed it had been laced with fentanyl, a powerful synthetic drug 50 times more potent than heroin. Just a tiny amount, as shown in this DEA photo below, can be lethal.

When emergency personnel arrived on the scene, they found two men already dead and another in need of immediate medical attention.

"He said he felt like his body was shutting down," Fitzpatrick said.

As police consoled the living man's grieving family members, fire marshals entered the home in hazmat suits to protect themselves from the drug's toxicity, which the DEA cautions can be inhaled or absorbed through the skin.

"Unfortunately we have to go through these extremes now because these drugs are so dangerous to make sure it's safe for first responders," Fitzpatrick said.

In Massachusetts, fentanyl was linked to 1,302 deaths last year, accounting for more than half -- 69 percent -- of all opioid-related deaths in the state.

A 22-year-old mother in Kentucky who had a little girl. A fifth grader in Miami who had just left a swimming pool. A police officer in Ohio who nearly died during an arrest.

These are just a handful of victims who have suffered fatal or near-fatal opioid overdoses this summer out of the tens of thousands of Americans who grapple with opioid addiction every day.

Opioids are a class of drugs that include the illegal drug heroin and powerful pain relievers available legally with a prescription, such as oxycodone, codeine and morphine, according to the National Institute on Drug Abuse.

The Centers for Disease Control say overdose deaths involving prescription opioids have quadrupled since 1999 and drug overdoses now kill more people every year than gun violence or car accidents.

"One American now dies of a drug overdose every 11 minutes and more than two million Americans are addicted to prescription painkillers," U.S. Attorney General Jeff Sessions said on July 20.

To take an in-depth look at the scope of the opioid epidemic, "Nightline" monitored fatal and near-fatal overdose cases for just one week in July.

Communities across the nation are trying to figure out new ways to pull the country out of this epidemic, from a program in Albuquerque, New Mexico, called "Addict to Athlete" to a family treatment drug court in Erie County, New York, that offers mental health counseling and access to a relapse center.

But health care officials point out that the most recent national report on the total number of opioid overdose deaths, put out by the CDC, is already two years old. There is such a lag in information gathering that many in the public health community have been calling for a national database of real-time tracking known as "syndromic surveillance."

Resources for Heroin and Opioid Addiction, Treatment and Support

The complicated task of tracking opioid overdoses

The most up-to-date national total of opioid overdose deaths comes from 2015, and complete data from 2016 isn't expected to be available until the end of this year. It takes a significant amount of time for data on the local level to bubble up and be analyzed nationally by the CDC.

By the time the CDC corrects for regional differences in how reports are confirmed, collected and defined, more than a year can pass.

In 2015, more than 33,000 Americans died from opioid overdoses, according to the CDC, which says preliminary data from 2016 suggests the total number of overdose deaths will increase.

Daniel Ciccarone, an associate editor for the International Journal of Drug Policy and professor at the University of California San Francisco School of Medicine, said the lag time of a year is an improvement from how data was collected a few years ago, but it’s still a problem for understanding the scope of the current epidemic.

"The numbers are extraordinary and it's easy to get kind of numbed when you're in that kind of event when you say, 'well, this has had more deaths than the Vietnam War, this has had more deaths in a given year than HIV-AIDS,'" Ciccarone said. "We're reached epidemic levels because this is of crisis proportions. It's going to require a crisis response: resources, time, effort, humanity, compassion of a historic proportion."

"Nightline" reached out to officials in all 50 states and the District of Columbia to determine how each track both fatal and non-fatal overdoses. Each state uses its own criteria to collect data and even the way one state defines an opioid overdose can differ from another. Most states are reluctant to label a death as an opioid overdose until it is confirmed by toxicology reports and the time each local district takes to finalize an individual death certificate can range anywhere from days to months.

There is also variation in terms of non-fatal opioid overdoses. The most current analysis of national hospital data by the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality shows 1.27 million emergency room visits or inpatient stays were for non-fatal overdoses in 2014 – the most recent year the data is available. Often, victims that don't end up in hospitals or morgues return to their lives without the overdose being documented. Few states conduct real-time monitoring of non-fatal overdoses from sources like hospital emergency departments and EMS reports.

Twenty states, Washington, D.C., and various hospital associations agreed to share with "Nightline" preliminary overdose data from the seven days covering July 17 through July 23. The results provide a patchwork of data that highlights the difficulty of rapidly tracking the victims of the opioid crisis. Each state that shared their info cautioned that their numbers would not represent the full scope of those who overdosed during our seven-day report.

WATCH PART 1 OF OUR REPORT:

WATCH PART 2 OF OUR REPORT:

"Nightline's" findings in tracking opioid overdoses across the country

"Nightline" found that public health departments and hospital associations in all 50 states collect opioid overdose data in vastly different ways. Some health care systems have to wait months after a person has died for toxicology reports to confirm an opioid contributed to the death. Other systems don't even track overdose visits to emergency rooms or calls to first responders.

After Arizona's Gov. Doug Ducey declared a state of emergency in June, state and local agencies there began working together to more quickly track suspected opioid overdoses. The state posts its opioid overdose data on a weekly basis. For the seven-day period "Nightline" tracked, there were 174 suspected opioid overdoses recorded. Of that number, 22 were fatal.

In Illinois, the state's Department of Public Health was able to provide hospital emergency department data that showed 273 opioid overdose visits during "Nightline's" seven-day timeline. This figure accounted for only 0.26 percent of total visits to Illinois hospitals, according to the state.

In New Jersey, the state's Department of Health was able to collect data from both hospital emergency department data (97 visits) and EMS reports (172 reports) over the seven days for "Nightline." But New Jersey State Police track overdose reports separately.

There is increasing recognition that real-time data can help communities respond to overdose outbreaks by stocking up on the opioid-reversing drug naloxone, commonly referred to by the brand name Narcan, and tracking the people selling illicit drugs. On day one of "Nightline's" seven-day report, the CDC announced $12 million in funding to 23 states and Washington, D.C., to better track opioid-related overdoses.

The National Institute on Drug Abuse's HIDTA (High Intensity Drug Trafficking Areas) program launched an overdose reporting application this January that is currently in use across 11 states and 38 counties. Called ODMap, the app allows first responders to quickly submit details about an overdose so it can be analyzed to detect trends.

"Even if it's only one person, one person can save one life, by entering data and maybe foreseeing something that might happen down the road. That makes it all worthwhile," Captain Richard Flynn of the Arlington, Massachusetts, police department told ABC affiliate WCVB.

The app was developed by the Washington/Baltimore HIDTA over the past year and continues to be rolled out in counties across the country. Since ODMap's pilot phase, over 3,000 overdoses have been reported by first responders using the app. It is this type of reporting on the local level that will ultimately provide the most accurate national picture.

Snohomish Health District in Washington state, which covers public health services in Snohomish County, worked with its local fire, police, EMS, hospitals and clinics to gather data for "Nightline" and shows 37 suspected opioid overdoses occurred during our seven-day period. Three of those overdoses resulted in death.

Some cities like Cincinnati have started posting real-time data that allows the public to pinpoint instances of heroin overdoses to specific hours and neighborhoods.

"I think it's really about building a community of how we can address this epidemic," Cincinnati Chief Data Officer Brandon Crowley told ABC affiliate WCPO. "Because it's not just Cincinnati, it's not just affecting Ohio. It's affecting the country."

American life under the opioid crisis

"Nightline" partnered with ABC affiliate stations across the country for this report, covering the opioid crisis in their communities and nationally from July 17 to July 23, and the following stories are just some snapshots from the lives of Americans affected by this epidemic.

This map illustrates our ABC affiliates' coverage of the opioid epidemic during the week of July 17 to 23:

These stories highlight those who overdosed, the families members left behind to pick up the pieces, the health care personnel trying to save lives, the law enforcement officers chasing down drug dealers, and city and state officials pushing legislation and funding to help combat the deadliest drug crisis in American history.

Lawrence, Massachusetts – Monday, July 17

It was just after sunrise in this manufacturing town when a man called 911.

"He was ingesting what he thought was cocaine," said Lawrence Police Chief James Fitzpatrick.

But testing later showed it had been laced with fentanyl, a powerful synthetic drug 50 times more potent than heroin. Just a tiny amount, as shown in this DEA photo below, can be lethal.

When emergency personnel arrived on the scene, they found two men already dead and another in need of immediate medical attention.

"He said he felt like his body was shutting down," Fitzpatrick said.

As police consoled the living man's grieving family members, fire marshals entered the home in hazmat suits to protect themselves from the drug's toxicity, which the DEA cautions can be inhaled or absorbed through the skin.

"Unfortunately we have to go through these extremes now because these drugs are so dangerous to make sure it's safe for first responders," Fitzpatrick said.

In Massachusetts, fentanyl was linked to 1,302 deaths last year, accounting for more than half -- 69 percent -- of all opioid-related deaths in the state.

Louisville, Kentucky – Monday, July 17

Veronica Jecker, 22, had been struggling with drug addiction for years, but this summer, her family was hopeful that she was finally on the right track.

She had been in and out of rehab, fighting to get clean so she could keep her job at a car company and care for her 4-year-old daughter, Raelyn.

A study published in the Journal of Substance Abuse Treatment in April found that patients with opioid use disorder, who had gone through short-term inpatient treatment, have a 70 percent relapse rate without the help of maintenance treatment, meaning access to naltrexone, a drug that blocks opioid effects. With naltrexone, the study found the relapse rate was reduced to 31 percent.

On Friday, July 14, Jecker checked herself out of rehab to spend the night with a friend and the following morning, around 7:15 a.m., her mother, Carrie Parsley, got a call saying she needed to get to the hospital as fast as possible.

"And they say, 'I'm sorry, please just-- we just need you to come here,'" she said. "And [I] just lose it."

By 2:30 p.m. on Monday, July 17, her daughter was officially pronounced dead from a heroin overdose.

"She was gone," said Jecker’s stepfather, Jay Parsley. "Our daughter, she was gone."

The Parsleys said they wanted to share their daughter's story as a warning to other parents.

"If I can save one mother from having to go through this pain of burying your child, I'll do it," Carrie Parsley said.

The one silver lining for them was that Jecker was an organ donor and her liver, kidneys and pancreas helped give three other people a chance to survive. According to the United Network for Organ Sharing, 28 organ donors nationwide died from a drug overdose that week.

"There would have been not one, not one good thing that would have come out of this” Jay Parsley said. “It made a little sense of a senseless situation."

Dr. Christopher Jones, the director of Transplant Services at KentuckyOne Health Jewish Hospital and a board member of Kentucky Organ Donor Affiliates, which facilitated Jecker’s organs, said dying from a drug overdose does not create a health issue for organ donation.

“It is perfectly fine for someone who passes away like this to have their organs donated, not a problem with us at all, and it's not a problem for the recipients either,” said Jones.

Miami, Florida -- Tuesday, July 18

At 3:30 p.m., Miami-Dade State Attorney Katherine Fernandez Rundle released the shocking results of a preliminary toxicology report.

The report suggested that 10-year-old Alton Banks had died on June 23 from an overdose of fentanyl mixed with heroin.

His friends said the fifth grader had gone to a nearby pool earlier that day, where he had swallowed some water, but then went home. Hours later, his family said he was vomiting. The boy's grandmother said his mother was concerned but didn't know her son was actually overdosing.

Eventually they called 911. Paramedics rushed him to the hospital, where Alton was later pronounced dead.

Police suspect that sometime between Alton's visit to the pool and his walk home afterward, the boy came into contact with fentanyl.

The dangerous potency of this drug has put the most innocent of lives at risk. According to the DEA, just touching a trace amount of the powerful opioid can be enough to send someone into an overdose.

How the drug got into Alton's system remains a mystery, but it is an example of how even an innocent child can fall victim.

East Liverpool, Ohio – Tuesday, July 18

Officer Chris Green knows all too well how dangerous inhaling or ingesting, or possibly even touching, small specks of fentanyl can be. Green nearly died when, during an arrest, he inadvertently came in contact with fentanyl.

Green has made tracking down opioid dealers and users his personal mission for nearly five years. Ohio has been one of the hardest hit in the opioid epidemic.

The CDC reported that drug overdose deaths in the Buckeye state increased 21.5 percent from 2014 to 2015 and the state is in the top five in the country for highest rates of death due to drug overdose. According to the Ohio Hospital Association, at least 605 people ended up in emergency rooms across the state for a suspected opioid overdose during the seven days of our reporting.

"We will go an entire shift and all we are dealing with is overdoses," Green said. "It's devastating to the communities."

The devastation this drug can leave behind was crystallized in the shocking photos posted on Facebook by the township of East Liverpool, where Green works. The photos showed a grandmother and her boyfriend both passed out from a heroin overdose, while a 4-year-old sat in the backseat of their car. Police used naloxone, an opioid-reversing medication, to revive the adults and called child services.

In explaining why they posted the photos, the city wrote on Facebook: "We feel we need to be a voice for the children caught up in this horrible mess. This child can't speak for himself, but we are hopeful his story can convince another user to think twice about injecting this poison while having a child in their custody."

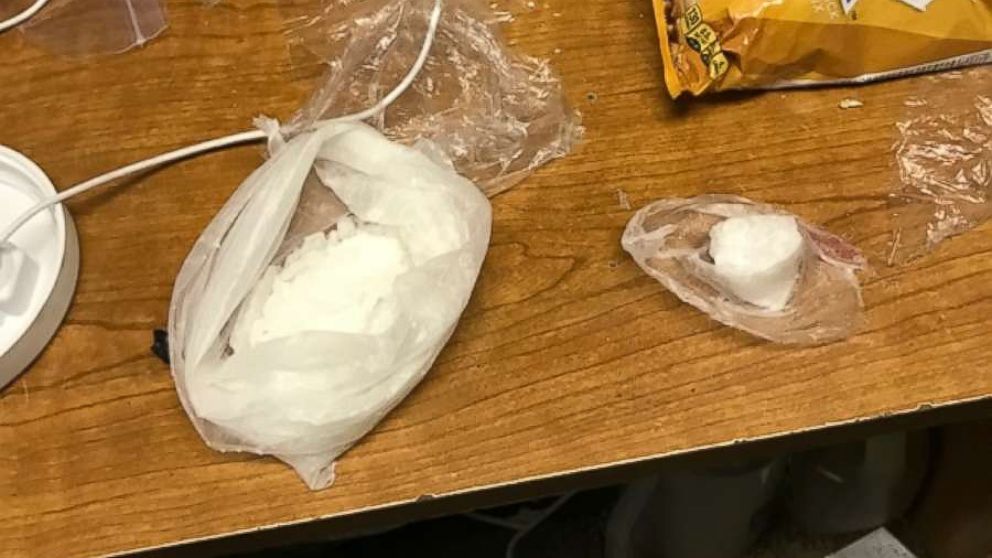

In a separate case, "Nightline" embedded with Green as he and the special response team executed a search warrant on a home that was suspected of having drugs. During the search, all of the adults on the premises were handcuffed while a boy who was also in the home looked on.

"What's the most disheartening is the young juvenile," Green said. "He is being exposed to things that no kid should."

About 20 grams of a powdery substance that the officers suspected was fentanyl was found inside the home. Police said they could not bring charges until lab results confirm the makeup of the powder.

Green says waiting for lab results in drug bust cases can take a long time, which means "nine out of 10 individuals will continue to sell, even after this drug bust," he said. Because of this lag, Green says that nearly every day, he has to let suspects from drug-related offenses back onto the streets, who he believes will just deal again.

"So in the meantime they will just continue to wreak havoc on these neighborhoods," he said. "It's a shame."

Elk Ridge, Utah – Tuesday, July 18

A couple was arrested after police discovered that they had been feeding their 3-month-old daughter drugs because she was born dependent on opioids.

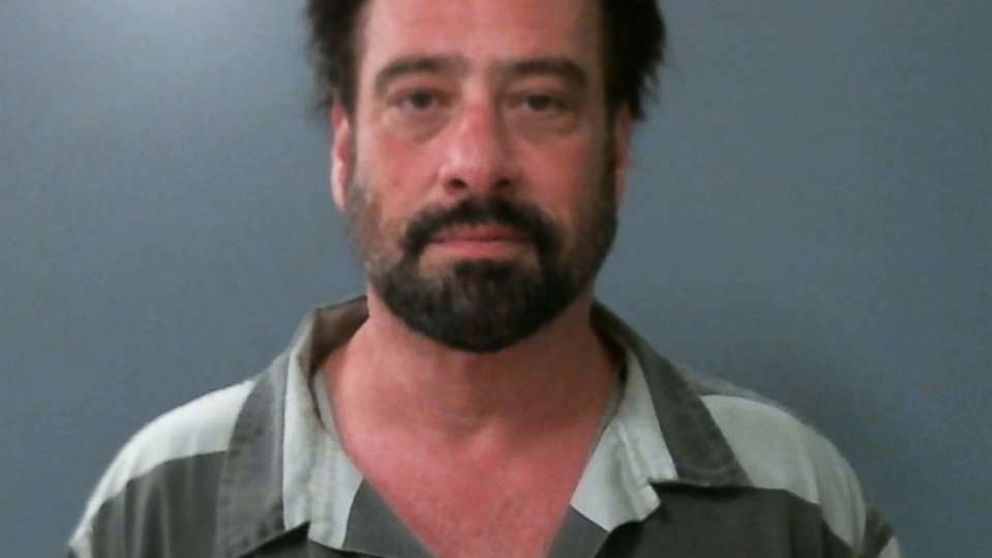

Police say the baby's parents, 29-year-old Colby Glen Wilde and 26-year-old Lacey Dawn Christenson, were trying to keep the baby from going through withdrawals.

"They would wet a finger, dip it in these crushed up pills, and then apply it to the gums of the child," said Sgt. Spencer Cannon from the Utah County Sheriff's Office. "It makes me sick to my stomach almost literally to think that the child who is relying on somebody for protection is being harmed by those who should be caring for them."

The couple were each charged with three counts of child abuse, a second-degree felony, according to the Salt Lake City newspaper, Deseret News.

They previously were charged with distribution of a controlled substance in a drug-free zone, possession of heroin and methamphetamine, endangerment of a child and possession of drug paraphernalia.

Christenson has not yet entered a plea. Wilde was in court for a plea hearing on Tuesday.

As the opioid epidemic grows, so do the numbers of babies born dependent on drugs. The use of opioids during pregnancy can result in a withdrawal syndrome known as neonatal abstinence syndrome or NAS.

In 2012, the CDC reported over 21,000 babies in the U.S. were born with NAS.

Sherman, Texas – Tuesday, July 18

Mike Tallis had been going to Dr. Howard Diamond, a longtime pain management physician, for prescription painkillers for injuries he said he sustained at his job a decade ago.

But when Tallis arrived that Tuesday, July 18, at Diamond’s office, he found the doors locked and the office empty.

Diamond had been arrested earlier that month on federal drug conspiracy charges that included conspiracy to distribute controlled substances, possession with intent to distribute controlled substances, health care fraud, aiding and abetting, and money laundering.

Federal authorities claimed Diamond's alleged conspiracy caused the overdose deaths of at least seven individuals from 2012 to 2016.

Among them was Tammy Curtis-Betterton.

"I shouldn't have to bury her," her sister, Kaylynn Curtis-Rhodes, told ABC affiliate WFAA. "I shouldn’t have to get to the cemetery to see my sister."

Diamond pleaded not guilty to all federal charges. In a statement to ABC News, his lawyer, Peter Schulte said, in part: "You can't blame the doctor if people are misusing their prescriptions. The allegations of the seven people that died happened over the last five years. Dr. Diamond has had hundreds, if not thousands, of patients over that time."

Mike Tallis was worried about where his next refill would come from. "I've got like five pills left," he said, and after that, "[I'll] have to go on the street and get them."

Delray Beach, Florida – Tuesday, July 18

Across 25 states, counties and cities have filed lawsuits against pharmaceutical companies for compensatory and punitive damages related to drug overdoses in their local communities.

One of those communities is Delray Beach -- the first city in Florida to file such a lawsuit.

Mayor Cary Glickstein said the city has spent more than $3 million responding to and treating overdoses.

"The human side of this is something you can't calculate. But the financial side of it is something that is calculable," Glickman said. "That lawsuit is looking for restitution."

The Florida Department of Health reported at least 337 visits to hospital emergency departments for suspected opioid overdoses during the seven days of "Nightline's" report.

Phoenix, Arizona – Wednesday, July 19

Arizona declared a health emergency earlier this summer to deal with the rapidly growing number of opioid deaths in the state.

During this week, first responders in the city of Phoenix alone responded to 278 drug overdose calls. Of the 278 calls, 134 were reported to be the result of an opioid derivative, according to the Phoenix fire department. Paramedics there said Narcan, the brand name for naloxone, is the second-most administered drug in the city.

"It could be the young, the old, doesn't matter if you live in a really nice house or barely scraping by in an apartment, unfortunately this drug [opioids] doesn't discriminate," said Phoenix Fire Department Capt. Rob McDade.

Phoenix and Tucson are major hubs for drug trafficking from Mexico into the U.S., according to the DEA. The agency says tons of narcotics come into these two cities, then the drugs are split, repackaged and sent to other parts of the country like Seattle, Denver, Minneapolis, Chicago and Philadelphia.

"One of the unique things about Arizona is that if you want to see what else is going to happen in drug trafficking and drug use in the United States, look at the dope that we're seizing in this state," said Doug Coleman, special agent in charge of the DEA Phoenix Field Division. "Because everything that's coming into the United States is coming into Arizona first."

At 1:30 p.m. on Wednesday, July 19, a DEA team, working with a joint-task force that included the Tempe Police Department and other law enforcement agencies, in Phoenix was trying to bring down an alleged multimillion-dollar drug ring.

DEA agents say this particular alleged drug ring was suspected of pushing out 15 pounds of heroin and any number of pills on a monthly basis. The illicit product they were allegedly selling was suspected of causing overdoses in the area.

Law enforcement officers and DEA agents tailed multiple suspects across the city. When one of the suspects, Silvestre Feilix-Beltran, pulled into a gas station, officers saw an opportunity to make an arrest. He was apprehended, handcuffed and taken away as agents searched his vehicle.

"We definitely already found what looks to be a large sum of money," said J. Todd Scott, Assistant Special Agent in Charge of DEA Phoenix Field Division. "And then we'll just continue to tear the vehicle down until we see if there's any more dope in here."

Beltran was later charged with conspiracy, illegal control of enterprise and dangerous narcotic drug violations, among other charges. He had not yet entered a plea at the time of publication, according to the Maricopa County Court, and his attorney did not immediately respond to "Nightline's" request for comment.

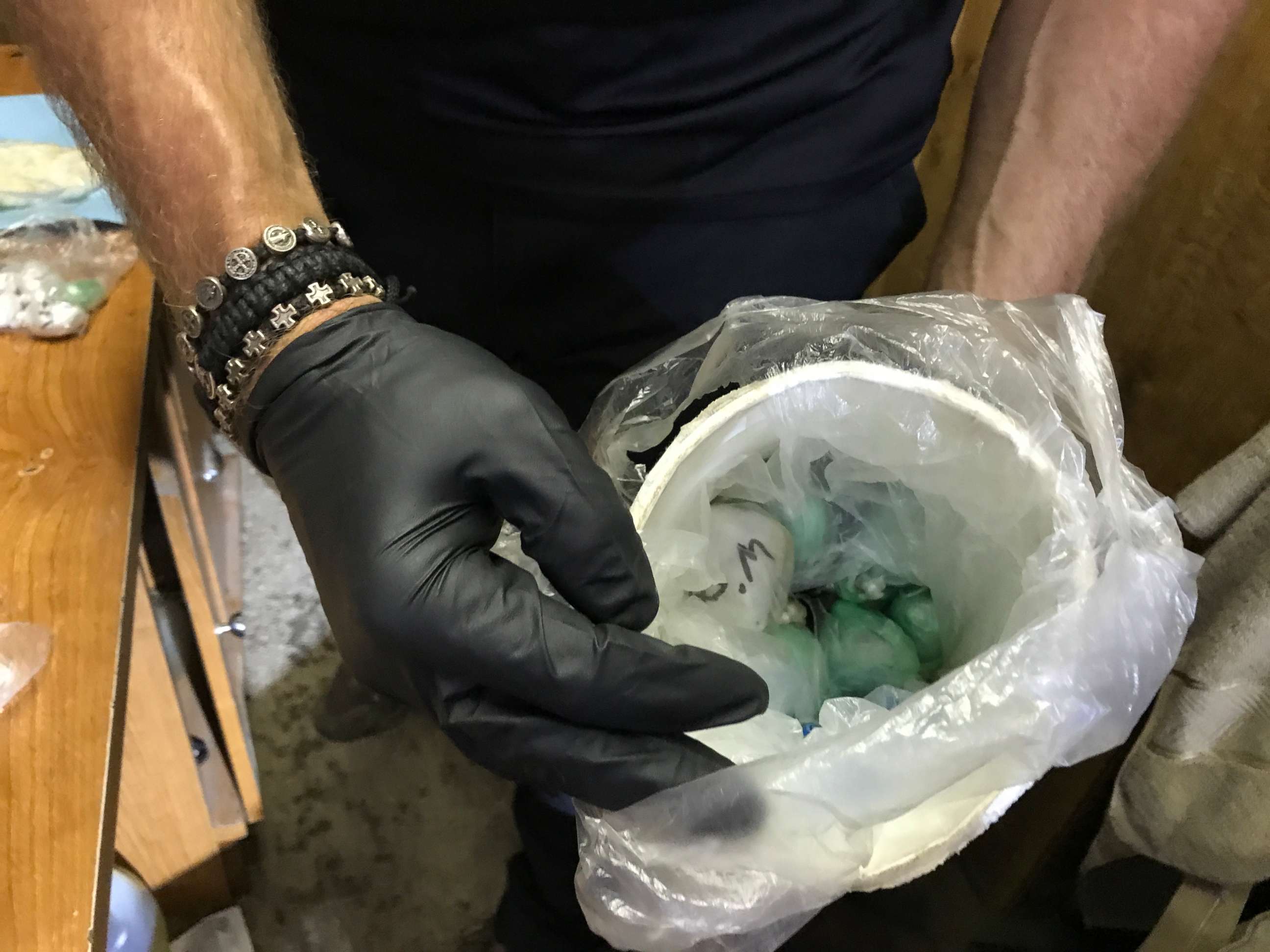

Next, the SWAT team and DEA agents got into position and searched a nearby trailer compound that was suspected to be connected to the alleged drug ring.

"We got bundled product there, scales, and spoons," said Scott, pointing to drugs they found inside an oatmeal container. "Most of what is going to be inside here is going to be heroin."

As night fell that same day, on the other side of town, DEA agents entered the house of their main target, Joel Lopez-Lopez, who was living in the home with another suspect, Maria Angalita Morales, according to the Tempe Police Department and the DEA.

Seven children were found in the home during the raid.

Lopez and others ran, sending agents on a foot chase. A helicopter was brought in to help with the search. It circled overhead and neighbors were cleared from the scene.

"He isn't only scared of us, but he is scared of this cartel that he is getting this dope from because he owes them money for this product," Coleman said. "So he's scared of a lot of different things."

Lopez was caught that evening. He was arrested and charged with sixteen counts, including conspiracy, illegal control of enterprise and narcotic drug possession for sale, according to the Maricopa County Court. He had not entered a plea at the time of publication and his attorney did not immediately respond to "Nightline's" request for comment.

The children found inside the home were put in state protective custody. Morales pleaded not guilty to the drug-related charges against her. Morales' lawyer declined "Nightline's" requests for comment.

The agents searched the home for hours, which yielded a shocking amount of suspected black tar heroin that one agent estimated was worth about $1 million and could provide "thousands of individual doses."

According to the DEA, this organization was running 40 to 50 pounds of heroin a month.

"One of the unique things about Arizona is that if you want to see what else is going to happen in drug trafficking and drug use in the United States, look at the dope that we're seizing in this state," said Doug Coleman, special agent in charge of the DEA Phoenix Field Division. "Because everything that's coming into the United States is coming into Arizona first."

At 1:30 p.m. on Wednesday, July 19, a DEA team, working with a joint-task force that included the Tempe Police Department and other law enforcement agencies, in Phoenix was trying to bring down an alleged multimillion-dollar drug ring.

DEA agents say this particular alleged drug ring was suspected of pushing out 15 pounds of heroin and any number of pills on a monthly basis. The illicit product they were allegedly selling was suspected of causing overdoses in the area.

Law enforcement officers and DEA agents tailed multiple suspects across the city. When one of the suspects, Silvestre Feilix-Beltran, pulled into a gas station, officers saw an opportunity to make an arrest. He was apprehended, handcuffed and taken away as agents searched his vehicle.

"We definitely already found what looks to be a large sum of money," said J. Todd Scott, Assistant Special Agent in Charge of DEA Phoenix Field Division. "And then we'll just continue to tear the vehicle down until we see if there's any more dope in here."

Beltran was later charged with conspiracy, illegal control of enterprise and dangerous narcotic drug violations, among other charges. He had not yet entered a plea at the time of publication, according to the Maricopa County Court, and his attorney did not immediately respond to "Nightline's" request for comment.

Next, the SWAT team and DEA agents got into position and searched a nearby trailer compound that was suspected to be connected to the alleged drug ring.

"We got bundled product there, scales, and spoons," said Scott, pointing to drugs they found inside an oatmeal container. "Most of what is going to be inside here is going to be heroin."

As night fell that same day, on the other side of town, DEA agents entered the house of their main target, Joel Lopez-Lopez, who was living in the home with another suspect, Maria Angalita Morales, according to the Tempe Police Department and the DEA.

Seven children were found in the home during the raid.

Lopez and others ran, sending agents on a foot chase. A helicopter was brought in to help with the search. It circled overhead and neighbors were cleared from the scene.

"He isn't only scared of us, but he is scared of this cartel that he is getting this dope from because he owes them money for this product," Coleman said. "So he's scared of a lot of different things."

Lopez was caught that evening. He was arrested and charged with sixteen counts, including conspiracy, illegal control of enterprise and narcotic drug possession for sale, according to the Maricopa County Court. He had not entered a plea at the time of publication and his attorney did not immediately respond to "Nightline's" request for comment.

The children found inside the home were put in state protective custody. Morales pleaded not guilty to the drug-related charges against her. Morales' lawyer declined "Nightline's" requests for comment.

The agents searched the home for hours, which yielded a shocking amount of suspected black tar heroin that one agent estimated was worth about $1 million and could provide "thousands of individual doses."

According to the DEA, this organization was running 40 to 50 pounds of heroin a month.

Manatee County, Florida – Friday, July 21

Manatee County is an area hit so hard by the opioid epidemic that now EMS, police and fire department all respond to drug overdose calls.

Manatee County EMS said almost half the money they have spent on medication this year has gone to Narcan. The 1,222 doses they have administrated this year costs the country $53,511.

In the days following an overdose, county paramedics now follow up with the people they have treated. One of them was 40-year-old Clay Alligood.

Two weeks prior, Alligood overdosed on heroin laced with fentanyl. He said "it's a lot easier" to stay off drugs when he can be around others who are clean.

Daniel Ciccarone with the International Journal of Drug Policy and UC-San Francisco School of Medicine said abusing these drugs can have significant effects on brain health and behavior.

Opioid abuse can create “a distinct loss of free will based on… long term chemical interactions with the brain,” he said. “Once the chemical is out after a year or so in recovery, they [can] look back and say, 'oh boy, what did I do there?'”

“The heroin epidemic, if you will, should be viewed as a disease much like alcoholism,” added paramedic Mark Regis. “I have had very close friends of mine that have battled this … and it’s a very tough struggle. As a paramedic on the front line of this, we see just a snippet of that.”

Resources for Heroin and Opioid Addiction, Treatment and Support

Additional Credits

Nightline Senior Broadcast Producer STEVE BAKER

Nightline Senior Producer GEOFF MARTZ

Nightline Graphic Designer ROGER WHITE

Coordinating Producer JACK DATE

Editor TARA FOWLER

Social MEREDITH FROST and LAURA COBURN

Intern CONNOR McCARTHY

Senior Developer GREG ATRIA