The Obama Legacy: A Promise of Hope

A Look Back at Eight Years of Victories and Defeats

By GARY WESTPHALEN and SERENA MARSHALL

“On this day, we gather because we have chosen hope over fear.”

These words of optimism rang out from banks of speakers, echoed across the West Lawn of the Capitol and down the length of the National Mall on a cold and blustery day in January 2009. An estimated 1.8 million people huddled in the cold, and tens of millions more around the world watched and listened on TV. With the Capitol, that symbol of democratic freedom and power as a backdrop, the message of hope was delivered.

Behind the podium, one man stood alone — Barack Hussein Obama, the 47-year-old son of a black father from Kenya and a white mother from Kansas after taking the oath of office. He was now the 44th president of the United States, after winning a historic election by some 10 million votes.

Obama’s message of hope was badly needed. Although more than seven years had passed since the 9/11 attacks shook the very foundation of this nation, the smoke had not yet cleared from our collective memory. The resulting wars in Iraq and Afghanistan had claimed thousands more American lives. Osama bin Laden, the man behind the history-altering attack, continued to elude capture even as he encouraged his followers to launch more terrorist strikes.

These words of optimism rang out from banks of speakers, echoed across the West Lawn of the Capitol and down the length of the National Mall on a cold and blustery day in January 2009. An estimated 1.8 million people huddled in the cold, and tens of millions more around the world watched and listened on TV. With the Capitol, that symbol of democratic freedom and power as a backdrop, the message of hope was delivered.

Behind the podium, one man stood alone — Barack Hussein Obama, the 47-year-old son of a black father from Kenya and a white mother from Kansas after taking the oath of office. He was now the 44th president of the United States, after winning a historic election by some 10 million votes.

Obama’s message of hope was badly needed. Although more than seven years had passed since the 9/11 attacks shook the very foundation of this nation, the smoke had not yet cleared from our collective memory. The resulting wars in Iraq and Afghanistan had claimed thousands more American lives. Osama bin Laden, the man behind the history-altering attack, continued to elude capture even as he encouraged his followers to launch more terrorist strikes.

An Economy on the Brink of Failure

The U.S. economy was firmly in the grips of a bad recession for more than a year before Obama became president. The housing market, shocked by a massive collapse of subprime mortgages, was reeling. Global financial companies like Lehman Brothers were in complete meltdown. American companies were shedding more than half a million jobs every month, and the Dow Jones Industrial Average had lost half its value.

Passage of the American Recovery and Reinvestment Act was the first major legislative success for the new president. Buoyed by substantial Democratic control of the House and Senate, the $787 billion stimulus bill was quickly passed and signed into law less than a month after he took office. It was an economic defibrillator designed to jolt the nation back to life.

But there was nothing quick about the recovery that followed. Unemployment continued to rise, peaking at 10.1 percent in October 2009. Millions of people had simply given up even trying to find a job. The nation’s gross domestic product continued to sputter. Opponents seized on these factors. Some liberal opponents argued the package wasn’t enough, while conservatives countered that the plan was too expensive and did little to restore the economy.

Nearly three years later, the nonpartisan Congressional Budget Office issued a report stating that the ARRA had in fact had a demonstrable impact on the nation, saving as many as 2.9 million jobs. But a sluggish economy has persisted with, for example, unemployment dropping to prerecession levels only in the closing months of the Obama administration.

The U.S. economy was firmly in the grips of a bad recession for more than a year before Obama became president. The housing market, shocked by a massive collapse of subprime mortgages, was reeling. Global financial companies like Lehman Brothers were in complete meltdown. American companies were shedding more than half a million jobs every month, and the Dow Jones Industrial Average had lost half its value.

Passage of the American Recovery and Reinvestment Act was the first major legislative success for the new president. Buoyed by substantial Democratic control of the House and Senate, the $787 billion stimulus bill was quickly passed and signed into law less than a month after he took office. It was an economic defibrillator designed to jolt the nation back to life.

But there was nothing quick about the recovery that followed. Unemployment continued to rise, peaking at 10.1 percent in October 2009. Millions of people had simply given up even trying to find a job. The nation’s gross domestic product continued to sputter. Opponents seized on these factors. Some liberal opponents argued the package wasn’t enough, while conservatives countered that the plan was too expensive and did little to restore the economy.

Nearly three years later, the nonpartisan Congressional Budget Office issued a report stating that the ARRA had in fact had a demonstrable impact on the nation, saving as many as 2.9 million jobs. But a sluggish economy has persisted with, for example, unemployment dropping to prerecession levels only in the closing months of the Obama administration.

Race in America – The Divide Widens

Obama was swept into office in 2008 on a tidal wave of support from racial and ethnic minorities. Election Day polling by ABC News found that 95 percent of African-Americans who cast ballots voted for Obama, as did two-thirds of Hispanic, Asian and other minorities. The polling showed a majority of Americans, including white voters, felt that the nation’s troubled history with race relations had finally turned a corner.

Still, racism dogged Obama’s campaign even before he clinched the Democratic nomination. Among the controversies he had to endure was the charge that he wasn’t eligible to run because he wasn’t born in The United States. The birther theory, long espoused by Donald Trump, has endured throughout Obama’s presidency despite the release of his Hawaiian birth certificate. Trump and Maricopa County, Arizona, Sheriff Joe Arpaio only recently let go of the issue.

Obama ran into trouble for his association with his longtime pastor, the Rev. Jeremiah Wright, who delivered sermons filled with racial biases. As he campaigned for the presidency, Obama tackled the subject head-on in a speech judged by many to be among the most potent discussions of race in decades.

“Race is an issue that I believe this nation cannot afford to ignore right now,” he said to an audience at the Constitution Center in Philadelphia. He used his personal story as “the son of a black man from Kenya and a white woman from Kansas” to validate the feelings of both black and white Americans. He acknowledged the anger many black Americans feel about poverty and lack of opportunities. He also recognized that “a similar anger exists within segments of the white community. Most working- and middle-class white Americans don't feel that they have been particularly privileged by their race.”

Then, in perhaps the most prescient line of his speech that day, Obama said, “I have never been so naive as to believe that we can get beyond our racial divisions in a single election cycle.”

Nearly nine years later, ABC News polling indicates declining race relations. In 2008, when he delivered that famous speech, 55 percent of American voters surveyed said they believe that race relations were “generally good.” As he leaves office, more than 63 percent said they believe relations have become “generally bad,” and a full 83 percent said they want the next president to put a “major focus” on improving the situation.

So did Obama's presidency do more to heal or divide the country on race? There is no watershed moment or presidential action on which to pin the answer. In reality, there may have been little this president could have done.

One major indicator of what has happened in the past eight years can be summed up in a single word. Ferguson. When Michael Brown, an unarmed black teenager, was shot and killed in broad daylight by a white police officer in August 2014, the town of Ferguson, Missouri, erupted into some of the worst, most racially charged riots in decades. A series of police shootings of unarmed black men, many of them recorded by cellphone cameras, followed, and the issue of racial injustice came into renewed focus. A loose organization that began with the hashtag #BlackLivesMatter exploded into international prominence after staging blunt public demonstrations objecting to the way black people have been treated historically by whites in this country and by police in particular. In response, slogans like “All lives matter,” in support of whites, and movements like Blue Lives Matter, in support of police, sprang up to counter Black Lives Matter.

Through all of this, Obama has walked a fine line. After the shooting death of Trayvon Martin in Florida, killed by George Zimmerman, who was patrolling as part of a neighborhood watch program, Obama opined, “If I had a son, he would look like Trayvon.” And when Alton Sterling was killed in Louisiana and Philando Castile was killed in Minnesota in 2016, both by police, Obama said, “These are not isolated incidents. They’re symptomatic of a broader set of racial disparities that exist in our criminal justice system.”

On the other side of the divide, just a few days later, Micah Johnson killed five Dallas police officers and wounded nine others because, he told Dallas police, he wanted to kill white people and cops in particular. The president praised law enforcement officers for the difficult role they fill in American society.

“The deepest fault lines of our democracy have suddenly been exposed, perhaps even widened,” Obama said. “ I understand how Americans are feeling. But Dallas, I’m here to say we must reject such despair. I’m here to insist we’re not as divided as we seem.”

Perhaps not. But his words and actions seem to have done little to assuage the critics. After the Dallas shootings, Texas Lt. Gov. Dan Patrick charged during an ABC News town hall that Obama didn’t go far enough to support police and “protect their lives.” On the other side, liberal political commentator and talk show host Tavis Smiley lamented that “black people lost ground in every single leading economic category during the Obama years.”

Obama was swept into office in 2008 on a tidal wave of support from racial and ethnic minorities. Election Day polling by ABC News found that 95 percent of African-Americans who cast ballots voted for Obama, as did two-thirds of Hispanic, Asian and other minorities. The polling showed a majority of Americans, including white voters, felt that the nation’s troubled history with race relations had finally turned a corner.

Still, racism dogged Obama’s campaign even before he clinched the Democratic nomination. Among the controversies he had to endure was the charge that he wasn’t eligible to run because he wasn’t born in The United States. The birther theory, long espoused by Donald Trump, has endured throughout Obama’s presidency despite the release of his Hawaiian birth certificate. Trump and Maricopa County, Arizona, Sheriff Joe Arpaio only recently let go of the issue.

Obama ran into trouble for his association with his longtime pastor, the Rev. Jeremiah Wright, who delivered sermons filled with racial biases. As he campaigned for the presidency, Obama tackled the subject head-on in a speech judged by many to be among the most potent discussions of race in decades.

“Race is an issue that I believe this nation cannot afford to ignore right now,” he said to an audience at the Constitution Center in Philadelphia. He used his personal story as “the son of a black man from Kenya and a white woman from Kansas” to validate the feelings of both black and white Americans. He acknowledged the anger many black Americans feel about poverty and lack of opportunities. He also recognized that “a similar anger exists within segments of the white community. Most working- and middle-class white Americans don't feel that they have been particularly privileged by their race.”

Then, in perhaps the most prescient line of his speech that day, Obama said, “I have never been so naive as to believe that we can get beyond our racial divisions in a single election cycle.”

Nearly nine years later, ABC News polling indicates declining race relations. In 2008, when he delivered that famous speech, 55 percent of American voters surveyed said they believe that race relations were “generally good.” As he leaves office, more than 63 percent said they believe relations have become “generally bad,” and a full 83 percent said they want the next president to put a “major focus” on improving the situation.

So did Obama's presidency do more to heal or divide the country on race? There is no watershed moment or presidential action on which to pin the answer. In reality, there may have been little this president could have done.

One major indicator of what has happened in the past eight years can be summed up in a single word. Ferguson. When Michael Brown, an unarmed black teenager, was shot and killed in broad daylight by a white police officer in August 2014, the town of Ferguson, Missouri, erupted into some of the worst, most racially charged riots in decades. A series of police shootings of unarmed black men, many of them recorded by cellphone cameras, followed, and the issue of racial injustice came into renewed focus. A loose organization that began with the hashtag #BlackLivesMatter exploded into international prominence after staging blunt public demonstrations objecting to the way black people have been treated historically by whites in this country and by police in particular. In response, slogans like “All lives matter,” in support of whites, and movements like Blue Lives Matter, in support of police, sprang up to counter Black Lives Matter.

Through all of this, Obama has walked a fine line. After the shooting death of Trayvon Martin in Florida, killed by George Zimmerman, who was patrolling as part of a neighborhood watch program, Obama opined, “If I had a son, he would look like Trayvon.” And when Alton Sterling was killed in Louisiana and Philando Castile was killed in Minnesota in 2016, both by police, Obama said, “These are not isolated incidents. They’re symptomatic of a broader set of racial disparities that exist in our criminal justice system.”

On the other side of the divide, just a few days later, Micah Johnson killed five Dallas police officers and wounded nine others because, he told Dallas police, he wanted to kill white people and cops in particular. The president praised law enforcement officers for the difficult role they fill in American society.

“The deepest fault lines of our democracy have suddenly been exposed, perhaps even widened,” Obama said. “ I understand how Americans are feeling. But Dallas, I’m here to say we must reject such despair. I’m here to insist we’re not as divided as we seem.”

Perhaps not. But his words and actions seem to have done little to assuage the critics. After the Dallas shootings, Texas Lt. Gov. Dan Patrick charged during an ABC News town hall that Obama didn’t go far enough to support police and “protect their lives.” On the other side, liberal political commentator and talk show host Tavis Smiley lamented that “black people lost ground in every single leading economic category during the Obama years.”

‘Obamacare’ – The Signature Accomplishment

The Affordable Care Act, designed to make health care available to every American, is such a signature accomplishment of this administration that it is most commonly known as “Obamacare.” But that signature may be written in disappearing ink. Republicans have been joined by the incoming administration of Donald Trump in their cry to repeal and replace Obamacare.

The program seeks to enroll the entire nation in some form of health care coverage, imposing tax penalties on those who don’t comply. The belief is that this form of universal coverage will ultimately reduce federal budget deficits by hundreds of billions of dollars by 2021. But opponents consider it a socialist takeover of the nation’s health care industry.

The roots of the program can be traced to President Bill Clinton’s desire to expand health coverage to 37 million Americans without insurance. Obama positioned it as one of his four main goals as president in 2008.

Passage of the wide-ranging act was acrimonious at best. More than a year of testy negotiations took place, and rhetoric became so heated that it was virtually impossible to separate fact from fiction. The bill passed in the House 219-212, with 34 Democrats and every single Republican voting “nay.”

At the bill signing, Vice President Joe Biden famously turned to the president, whispering in his ear, caught on a microphone saying the passage was “big f---ing deal.”

Republicans introduced a bill to repeal the law the very next day and have tried unsuccessfully to do so more than 60 times since.

“Obamacare” has had other challenges as well. Some states opted out of the creation of health care exchanges, and some insurance companies have pulled out of those marketplaces. The law has faced numerous court challenges, with one reaching all the way to the Supreme Court, where the tenets of “Obamacare” were upheld. Contrary to the president’s words, some people lost their existing insurance policies, and many people were no longer to able to see the same doctor they had been going to for years. Then, when the online insurance exchanges, where eligible Americans could go to purchase the mandated levels of insurance came online, they crashed just as quickly. Weeks of computer failures, frustrations and anti-”Obamacare” rhetoric filled the air.

Despite the issues and ongoing Republican attacks, the Affordable Care Act has had a significant impact. The Census Bureau reports that the number of uninsured Americans has dropped from 16 percent in 2010 to less than 9 percent today — a decrease of 23 million people. And a recent report estimated that 24,000 lives have been saved from premature deaths because of the ability to get health care access.

While the president admits premiums have increased, he points to the slowed growth of the health insurance market as a cost savings to those who receive employer-based health care. On average, Obama told a Miami audience, consumers are paying $3,600 less for insurance than if premiums had continued to rise at the rate they were before the legislation was passed.

The law also made it illegal for insurance companies to discriminate against existing conditions, banned lifetime limits and made birth control free.

The Affordable Care Act, designed to make health care available to every American, is such a signature accomplishment of this administration that it is most commonly known as “Obamacare.” But that signature may be written in disappearing ink. Republicans have been joined by the incoming administration of Donald Trump in their cry to repeal and replace Obamacare.

The program seeks to enroll the entire nation in some form of health care coverage, imposing tax penalties on those who don’t comply. The belief is that this form of universal coverage will ultimately reduce federal budget deficits by hundreds of billions of dollars by 2021. But opponents consider it a socialist takeover of the nation’s health care industry.

The roots of the program can be traced to President Bill Clinton’s desire to expand health coverage to 37 million Americans without insurance. Obama positioned it as one of his four main goals as president in 2008.

Passage of the wide-ranging act was acrimonious at best. More than a year of testy negotiations took place, and rhetoric became so heated that it was virtually impossible to separate fact from fiction. The bill passed in the House 219-212, with 34 Democrats and every single Republican voting “nay.”

At the bill signing, Vice President Joe Biden famously turned to the president, whispering in his ear, caught on a microphone saying the passage was “big f---ing deal.”

Republicans introduced a bill to repeal the law the very next day and have tried unsuccessfully to do so more than 60 times since.

“Obamacare” has had other challenges as well. Some states opted out of the creation of health care exchanges, and some insurance companies have pulled out of those marketplaces. The law has faced numerous court challenges, with one reaching all the way to the Supreme Court, where the tenets of “Obamacare” were upheld. Contrary to the president’s words, some people lost their existing insurance policies, and many people were no longer to able to see the same doctor they had been going to for years. Then, when the online insurance exchanges, where eligible Americans could go to purchase the mandated levels of insurance came online, they crashed just as quickly. Weeks of computer failures, frustrations and anti-”Obamacare” rhetoric filled the air.

Despite the issues and ongoing Republican attacks, the Affordable Care Act has had a significant impact. The Census Bureau reports that the number of uninsured Americans has dropped from 16 percent in 2010 to less than 9 percent today — a decrease of 23 million people. And a recent report estimated that 24,000 lives have been saved from premature deaths because of the ability to get health care access.

While the president admits premiums have increased, he points to the slowed growth of the health insurance market as a cost savings to those who receive employer-based health care. On average, Obama told a Miami audience, consumers are paying $3,600 less for insurance than if premiums had continued to rise at the rate they were before the legislation was passed.

The law also made it illegal for insurance companies to discriminate against existing conditions, banned lifetime limits and made birth control free.

The Killing of Osama bin Laden

A week after the Sept. 11, 2001, attacks, George W. Bush addressed a stunned nation.

“I want justice,” Bush said. “There’s an old poster out west that I recall that said, ‘Wanted: Dead or alive.’”

Bush would not get his wish while in office.

For nearly a decade, the search for 9/11 mastermind Osama bin Laden wandered from eastern Afghanistan to Pakistan and even Iran. Lead after lead evaporated. Bin Laden grew more ghostlike as the years passed.

Nearly 10 years later, through a publicly murky series of events, tips and surveillance efforts, U.S. intelligence agencies came to the conclusion that bin Laden was holed up in a walled compound in Abbottabad, Pakistan. Months of surveillance and planning ensued, and Obama gave his final green light to a helicopter raid of the compound on April 29, 2011.

Two days later, about two dozen Navy SEALs descended on the compound from stealth helicopters, one of which struck the wall of the compound and soft crashed. The raid on the compound continued, and bin Laden was shot dead, along with four other occupants.

As he sat in the White House Situation Room, watching the night vision video feed from a drone flying above the compound, Obama is reported to have simply said, “We got him.”

Obama made immediate plans to announce the killing of bin Laden in a nationwide television address. But rumors of the killing broke on social media more than an hour before he would step in front of the camera to deliver the news. Shortly before midnight on May 1, 2011, he made it official.

“I can report to the American people and to the world that the United States has conducted an operation that killed Osama bin Laden,” the president began. He reminded the world that nearly 3,000 American lives had been lost on 9/11, and that the United States would be “relentless” in its efforts to hunt down terrorists. “And on nights like this one,” he added, “we can say to those families who have lost loved ones to al-Qaeda's terror, justice has been done.”

A week after the Sept. 11, 2001, attacks, George W. Bush addressed a stunned nation.

“I want justice,” Bush said. “There’s an old poster out west that I recall that said, ‘Wanted: Dead or alive.’”

Bush would not get his wish while in office.

For nearly a decade, the search for 9/11 mastermind Osama bin Laden wandered from eastern Afghanistan to Pakistan and even Iran. Lead after lead evaporated. Bin Laden grew more ghostlike as the years passed.

Nearly 10 years later, through a publicly murky series of events, tips and surveillance efforts, U.S. intelligence agencies came to the conclusion that bin Laden was holed up in a walled compound in Abbottabad, Pakistan. Months of surveillance and planning ensued, and Obama gave his final green light to a helicopter raid of the compound on April 29, 2011.

Two days later, about two dozen Navy SEALs descended on the compound from stealth helicopters, one of which struck the wall of the compound and soft crashed. The raid on the compound continued, and bin Laden was shot dead, along with four other occupants.

As he sat in the White House Situation Room, watching the night vision video feed from a drone flying above the compound, Obama is reported to have simply said, “We got him.”

Obama made immediate plans to announce the killing of bin Laden in a nationwide television address. But rumors of the killing broke on social media more than an hour before he would step in front of the camera to deliver the news. Shortly before midnight on May 1, 2011, he made it official.

“I can report to the American people and to the world that the United States has conducted an operation that killed Osama bin Laden,” the president began. He reminded the world that nearly 3,000 American lives had been lost on 9/11, and that the United States would be “relentless” in its efforts to hunt down terrorists. “And on nights like this one,” he added, “we can say to those families who have lost loved ones to al-Qaeda's terror, justice has been done.”

Same-Sex Marriage – A President Evolves

There is perhaps no social issue that has elicited stronger responses in recent times than same-sex marriage. Presidents had demurred on addressing the issue at the national level, and Obama did so as well at first. But his position has evolved over time, slowly and steadily.

Obama exploded onto the national scene in the summer of 2004, when he took the stage at the Democratic National Convention. His keynote speech was so strong that it immediately ignited presidential talk among fellow Democrats. But first, he was running for the U.S. Senate, an election he won that November.

When the newly elected senator sat down with MTV for an interview, he addressed the subject of same-sex marriage, flatly stating that he was “not in favor of gay marriage.” Four years later, as he and Hillary Clinton were battling for the Democratic presidential nomination, he doubled down. “I believe that marriage is the union between a man and a woman,” Obama said. “For me as a Christian, it is a sacred union. You know, God is in the mix.”

But other forces were at work as well. Public opinion, a California referendum, federal legislation and court opinions appeared to be converging on a path toward legal recognition of same-sex marriage, with or without him. In 2010, Obama expressed support for civil unions, equivalent in many ways with marriage, and admitted that his opinion was “evolving.”

The final step of an evolution often requires a catalyst, some outside influence that imposes itself on the process and makes things happen. In this case, the catalyst for the final step of the president’s evolution was Biden, who told the audience of a Sunday morning talk show in 2012 that he was “absolutely comfortable” with same-sex marriage.

All eyes turned to the president. Insisting in an interview with ABC’s Robin Roberts that he was going to say it anyway, Obama became the first president to say, while in office, that he supported same-sex marriage. But he was quick to add that the legal questions surrounding the issue should be left up to the states.

Then in 2013, the Supreme Court heard a case challenging the Defense of Marriage Act, a mid-1990s law that barred the federal government from recognizing same-sex couples as spouses. The high court overturned a key provision of DOMA, ruling that it violated the Fifth Amendment by singling out a class of people for discrimination.

Obama’s final evolution on the subject came the next year, when he said, “Ultimately, I think the equal protection clause does guarantee same-sex marriage in all 50 states.”

There is perhaps no social issue that has elicited stronger responses in recent times than same-sex marriage. Presidents had demurred on addressing the issue at the national level, and Obama did so as well at first. But his position has evolved over time, slowly and steadily.

Obama exploded onto the national scene in the summer of 2004, when he took the stage at the Democratic National Convention. His keynote speech was so strong that it immediately ignited presidential talk among fellow Democrats. But first, he was running for the U.S. Senate, an election he won that November.

When the newly elected senator sat down with MTV for an interview, he addressed the subject of same-sex marriage, flatly stating that he was “not in favor of gay marriage.” Four years later, as he and Hillary Clinton were battling for the Democratic presidential nomination, he doubled down. “I believe that marriage is the union between a man and a woman,” Obama said. “For me as a Christian, it is a sacred union. You know, God is in the mix.”

But other forces were at work as well. Public opinion, a California referendum, federal legislation and court opinions appeared to be converging on a path toward legal recognition of same-sex marriage, with or without him. In 2010, Obama expressed support for civil unions, equivalent in many ways with marriage, and admitted that his opinion was “evolving.”

The final step of an evolution often requires a catalyst, some outside influence that imposes itself on the process and makes things happen. In this case, the catalyst for the final step of the president’s evolution was Biden, who told the audience of a Sunday morning talk show in 2012 that he was “absolutely comfortable” with same-sex marriage.

All eyes turned to the president. Insisting in an interview with ABC’s Robin Roberts that he was going to say it anyway, Obama became the first president to say, while in office, that he supported same-sex marriage. But he was quick to add that the legal questions surrounding the issue should be left up to the states.

Then in 2013, the Supreme Court heard a case challenging the Defense of Marriage Act, a mid-1990s law that barred the federal government from recognizing same-sex couples as spouses. The high court overturned a key provision of DOMA, ruling that it violated the Fifth Amendment by singling out a class of people for discrimination.

Obama’s final evolution on the subject came the next year, when he said, “Ultimately, I think the equal protection clause does guarantee same-sex marriage in all 50 states.”

Climate Change – Legacy Laws to the Rescue

“We will harness the sun and the winds and the soil to fuel our cars and run our factories.” It was just one sentence in Obama’s first inaugural address. But it would lay the groundwork for the new president’s environmental policy for the next eight years.

In his first major initiative, the American Recovery and Reinvestment Act, Obama sought to inject billions of dollars into the development of green energy projects, committing an estimated $150 billion federal dollars during his first term in office.

Not all of that money brought dividends. For example, ARRA money was used to place a $535 million dollar loan in the hands of Solyndra, a California company that was trying to develop a complicated solar technology before it went bankrupt in 2011.The way the White House pushed the deal through was instrumental in a quickly worsening relationship between Obama and Capitol Hill.

Obama wasn’t going to let a stalled Congress stop his action on the environment, reaching back to a decades-old law to shape modern policy. He relied on the Clean Air Act of 1970 to shape Environmental Protection Agency regulations and the Outer Continental Shelf Lands Act of 1953 to protect the Arctic from oil drilling.

Obama’s Clean Power Plan debuted in August 2015 and set stiff carbon emission standards for power plants. He envisioned using less coal, more natural gas and more renewable energy sources, coupled with reduced demand, as the way to get there. The Clean Power Plan was, he said, “the single most important step that America has ever made in the fight against global climate change.”

The move was immediately attacked by Republicans as a war on coal, and dozens of states filed suit. The Supreme Court ordered the EPA to halt enforcement as their case made its way through the courts. The suit is pending and will not be resolved before Obama’s term ends.

With only a month left in his presidency, Obama utilized the 1953 Lands Act to remove leasing options for any Arctic drilling in the future. Under Obama’s tenure, nearly 125 million acres in the Arctic have been protected from future oil and gas development.

On the international front, the farthest-reaching environmental action is the Paris Agreement, which seeks to permanently limit the global average temperature to an increase of 2 degrees Celsius or less.

He created the largest marine preserve in the world, quadrupling the size of the Papahanaumokuakea Marine National Monument; reached a deal with carmakers to increase fuel economy to 54.5 miles per gallon by 2025; designated more than 2 million acres of federal wilderness by signing the bipartisan Public Land Management Act of 2009, which the White House called the “most extensive expansion of land and water conservation in more than a generation.”

The incoming administration has the power to override much of Obama’s Clean Power Plan, and since the Paris Agreement is not a treaty ratified by the Senate, the next administration may ignore it. But his national parks and ban on Arctic drilling will remain, securing a more pristine landscape, as he says, for the next generation.

“We will harness the sun and the winds and the soil to fuel our cars and run our factories.” It was just one sentence in Obama’s first inaugural address. But it would lay the groundwork for the new president’s environmental policy for the next eight years.

In his first major initiative, the American Recovery and Reinvestment Act, Obama sought to inject billions of dollars into the development of green energy projects, committing an estimated $150 billion federal dollars during his first term in office.

Not all of that money brought dividends. For example, ARRA money was used to place a $535 million dollar loan in the hands of Solyndra, a California company that was trying to develop a complicated solar technology before it went bankrupt in 2011.The way the White House pushed the deal through was instrumental in a quickly worsening relationship between Obama and Capitol Hill.

Obama wasn’t going to let a stalled Congress stop his action on the environment, reaching back to a decades-old law to shape modern policy. He relied on the Clean Air Act of 1970 to shape Environmental Protection Agency regulations and the Outer Continental Shelf Lands Act of 1953 to protect the Arctic from oil drilling.

Obama’s Clean Power Plan debuted in August 2015 and set stiff carbon emission standards for power plants. He envisioned using less coal, more natural gas and more renewable energy sources, coupled with reduced demand, as the way to get there. The Clean Power Plan was, he said, “the single most important step that America has ever made in the fight against global climate change.”

The move was immediately attacked by Republicans as a war on coal, and dozens of states filed suit. The Supreme Court ordered the EPA to halt enforcement as their case made its way through the courts. The suit is pending and will not be resolved before Obama’s term ends.

With only a month left in his presidency, Obama utilized the 1953 Lands Act to remove leasing options for any Arctic drilling in the future. Under Obama’s tenure, nearly 125 million acres in the Arctic have been protected from future oil and gas development.

On the international front, the farthest-reaching environmental action is the Paris Agreement, which seeks to permanently limit the global average temperature to an increase of 2 degrees Celsius or less.

He created the largest marine preserve in the world, quadrupling the size of the Papahanaumokuakea Marine National Monument; reached a deal with carmakers to increase fuel economy to 54.5 miles per gallon by 2025; designated more than 2 million acres of federal wilderness by signing the bipartisan Public Land Management Act of 2009, which the White House called the “most extensive expansion of land and water conservation in more than a generation.”

The incoming administration has the power to override much of Obama’s Clean Power Plan, and since the Paris Agreement is not a treaty ratified by the Senate, the next administration may ignore it. But his national parks and ban on Arctic drilling will remain, securing a more pristine landscape, as he says, for the next generation.

Criminal Justice Reform – Fixing a Broken System

Most first-term presidents don’t grant many requests from federal prisoners for pardons or clemency. Obama was no different, approving only a few dozen petitions of the more than 8,400 filed during his first four years in the Oval Office. That changed in April 2014, when Obama’s Justice Department announced the launch of the Clemency Initiative. The program was designed to provide relief for many low-level drug offenders with little or no other criminal history sentenced under Ronald Reagan–era drug laws that had since been revised.

“These older, stringent punishments that are out of line with sentences imposed under today’s laws erode people’s confidence in our criminal justice system,” stated Deputy Attorney General James M. Cole.

Criminal justice reform is one of a very few issues to have received bipartisan support during the Obama years, and the Clemency Initiative has been particularly successful. In all, Obama has issued 148 pardons and 1,176 sentence commutations — more than any other president since Lyndon Johnson.

Although some commutations have resulted in sentence reductions for prisoners who will continue to serve time, the bulk have resulted in outright release of inmates who have already served long sentences.

Some groups, such as the NAACP, have accused the process as being too slow and urged the president to issue blanket commutations for large numbers of prisoners. At the same time, during his campaign,Donald Trump seemed to suggest that he would end the Clemency Initiative.

Beneficiaries of Obama’s Clemency Initiative include people like Shauna Barry-Scott, a Youngstown, Ohio, grandmother of 17 who was sentenced to 20 years in federal prison for the sale of a small amount of crack cocaine.

Aside from the Clemency Initiative, Obama has not been able to move the needle very far on reforming the criminal justice system. But that hasn’t stopped him from advocating for significant change.

“The United States is home to 5 percent of the world’s population but 25 percent of the world’s prisoners,” he pointed out in a speech to the NAACP. This high rate of incarceration, he added, has had a high cost for families and taxpayers alike but done little to make the nation safer. It is also, he said, skewed in racial terms. “African-Americans and Latinos make up 30 percent of our population. They make up 60 percent of our inmates.” He added that our criminal justice system isn’t “smart” enough and that we “need to do something about it.”

The very next day, Obama became the first sitting U.S. president to visit a federal prison. Speaking about the inmates in El Reno Federal Correction Institution in Oklahoma where he was standing, he declared, “We have to make sure that as they do their time and pay back their debt to society, that we are increasing the possibility that they can turn their lives around.”

Aside from the Clemency Initiative, Obama’s efforts to reform the criminal justice system have been limited. As Trump assumes the presidency, even that appears in jeopardy. Trump has expressed skepticism about reducing criminal penalties, and his pick to lead the Justice Department, Sen. Jeff Sessions, was a vocal critic while in the Senate. “The last thing we need to do is a major reduction in penalties,” Sessions said in May of 2016.

Most first-term presidents don’t grant many requests from federal prisoners for pardons or clemency. Obama was no different, approving only a few dozen petitions of the more than 8,400 filed during his first four years in the Oval Office. That changed in April 2014, when Obama’s Justice Department announced the launch of the Clemency Initiative. The program was designed to provide relief for many low-level drug offenders with little or no other criminal history sentenced under Ronald Reagan–era drug laws that had since been revised.

“These older, stringent punishments that are out of line with sentences imposed under today’s laws erode people’s confidence in our criminal justice system,” stated Deputy Attorney General James M. Cole.

Criminal justice reform is one of a very few issues to have received bipartisan support during the Obama years, and the Clemency Initiative has been particularly successful. In all, Obama has issued 148 pardons and 1,176 sentence commutations — more than any other president since Lyndon Johnson.

Although some commutations have resulted in sentence reductions for prisoners who will continue to serve time, the bulk have resulted in outright release of inmates who have already served long sentences.

Some groups, such as the NAACP, have accused the process as being too slow and urged the president to issue blanket commutations for large numbers of prisoners. At the same time, during his campaign,Donald Trump seemed to suggest that he would end the Clemency Initiative.

Beneficiaries of Obama’s Clemency Initiative include people like Shauna Barry-Scott, a Youngstown, Ohio, grandmother of 17 who was sentenced to 20 years in federal prison for the sale of a small amount of crack cocaine.

Aside from the Clemency Initiative, Obama has not been able to move the needle very far on reforming the criminal justice system. But that hasn’t stopped him from advocating for significant change.

“The United States is home to 5 percent of the world’s population but 25 percent of the world’s prisoners,” he pointed out in a speech to the NAACP. This high rate of incarceration, he added, has had a high cost for families and taxpayers alike but done little to make the nation safer. It is also, he said, skewed in racial terms. “African-Americans and Latinos make up 30 percent of our population. They make up 60 percent of our inmates.” He added that our criminal justice system isn’t “smart” enough and that we “need to do something about it.”

The very next day, Obama became the first sitting U.S. president to visit a federal prison. Speaking about the inmates in El Reno Federal Correction Institution in Oklahoma where he was standing, he declared, “We have to make sure that as they do their time and pay back their debt to society, that we are increasing the possibility that they can turn their lives around.”

Aside from the Clemency Initiative, Obama’s efforts to reform the criminal justice system have been limited. As Trump assumes the presidency, even that appears in jeopardy. Trump has expressed skepticism about reducing criminal penalties, and his pick to lead the Justice Department, Sen. Jeff Sessions, was a vocal critic while in the Senate. “The last thing we need to do is a major reduction in penalties,” Sessions said in May of 2016.

Iran – Nuclear Centrifuges, Hostages and a Planeload of Cash

U.S. relations with most Middle Eastern nations have always been complex, and those with Iran — with its potential for nuclear weapons — have been particularly fraught.

Years-long negotiations resulted in a 2015 agreement under which Iran would give up much of its nuclear program in exchange for getting sanctions against it lifted. Iran has agreed to dismantle some nuclear facilities, mothball others, allow international inspection of remaining operations and ship much of its nuclear fuel and waste materials to other countries, including the United States.

But the deal, formally called the Joint Comprehensive Plan of Action, was not without its detractors. Israeli Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu delivered an unprecedented speech by a foreign leader to a joint session of Congress. “This is a bad deal,” he said. “It’s a very bad deal. We’re better off without it.” But he would not get his way, as Democrats in the Senate managed to block Republican efforts to kill the deal.

When the nuclear deal was finalized in January 2016, five American prisoners were released by Tehran. Months later, The Wall Street Journal broke the story that as soon as the Americans were released, the United States sent a planeload of cash to Tehran. Some $400 million worth of euros, Swiss francs and other non-U.S. currencies had been piled onto pallets and flown to Iran. To some, it appeared that the United States had paid a tidy ransom for the prisoners.

The State Department quickly insisted that wasn’t true, saying the U.S. had owed the money to Iran for decades to settle a dispute over military hardware purchases. The agency also insisted that the timing of the money transfer was merely “leverage” to ensure their safe release.

“We do not pay ransom. We didn’t here,” concurred Obama in an August news conference. He insisted the money, the prisoners and the nuclear deal really had nothing to do with one another, except that “we actually had diplomatic relations negotiations and conversations with Iran for the first time in several decades.”

Outraged Republicans were not moved by the argument. “If it quacks like a duck, it’s a duck.” said Sen. Ben Sasse, R-Neb. “If a cash payment is contingent on a hostage release, it’s a ransom.”

Despite widespread concerns about how enforceable the nuclear deal is, the agreement stands. Economic sanctions against Iran are being reduced step by step as the nation dismantles some of its nuclear infrastructure and agrees to international inspections of its remaining nuclear programs. The goal is to allow peacetime uses of nuclear power without the ability to generate weapons for years to come.

But Trump has blasted the deal and might seek to undermine it. Incoming Vice President Mike Pence has even gone so far as to say the new administration will “rip up” the agreement. That’s possible, but it won’t be easy. Six other nations are parties, and none of them have expressed any desire to alter it. Also, many of the provisions in it have already been set in motion.

U.S. relations with most Middle Eastern nations have always been complex, and those with Iran — with its potential for nuclear weapons — have been particularly fraught.

Years-long negotiations resulted in a 2015 agreement under which Iran would give up much of its nuclear program in exchange for getting sanctions against it lifted. Iran has agreed to dismantle some nuclear facilities, mothball others, allow international inspection of remaining operations and ship much of its nuclear fuel and waste materials to other countries, including the United States.

But the deal, formally called the Joint Comprehensive Plan of Action, was not without its detractors. Israeli Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu delivered an unprecedented speech by a foreign leader to a joint session of Congress. “This is a bad deal,” he said. “It’s a very bad deal. We’re better off without it.” But he would not get his way, as Democrats in the Senate managed to block Republican efforts to kill the deal.

When the nuclear deal was finalized in January 2016, five American prisoners were released by Tehran. Months later, The Wall Street Journal broke the story that as soon as the Americans were released, the United States sent a planeload of cash to Tehran. Some $400 million worth of euros, Swiss francs and other non-U.S. currencies had been piled onto pallets and flown to Iran. To some, it appeared that the United States had paid a tidy ransom for the prisoners.

The State Department quickly insisted that wasn’t true, saying the U.S. had owed the money to Iran for decades to settle a dispute over military hardware purchases. The agency also insisted that the timing of the money transfer was merely “leverage” to ensure their safe release.

“We do not pay ransom. We didn’t here,” concurred Obama in an August news conference. He insisted the money, the prisoners and the nuclear deal really had nothing to do with one another, except that “we actually had diplomatic relations negotiations and conversations with Iran for the first time in several decades.”

Outraged Republicans were not moved by the argument. “If it quacks like a duck, it’s a duck.” said Sen. Ben Sasse, R-Neb. “If a cash payment is contingent on a hostage release, it’s a ransom.”

Despite widespread concerns about how enforceable the nuclear deal is, the agreement stands. Economic sanctions against Iran are being reduced step by step as the nation dismantles some of its nuclear infrastructure and agrees to international inspections of its remaining nuclear programs. The goal is to allow peacetime uses of nuclear power without the ability to generate weapons for years to come.

But Trump has blasted the deal and might seek to undermine it. Incoming Vice President Mike Pence has even gone so far as to say the new administration will “rip up” the agreement. That’s possible, but it won’t be easy. Six other nations are parties, and none of them have expressed any desire to alter it. Also, many of the provisions in it have already been set in motion.

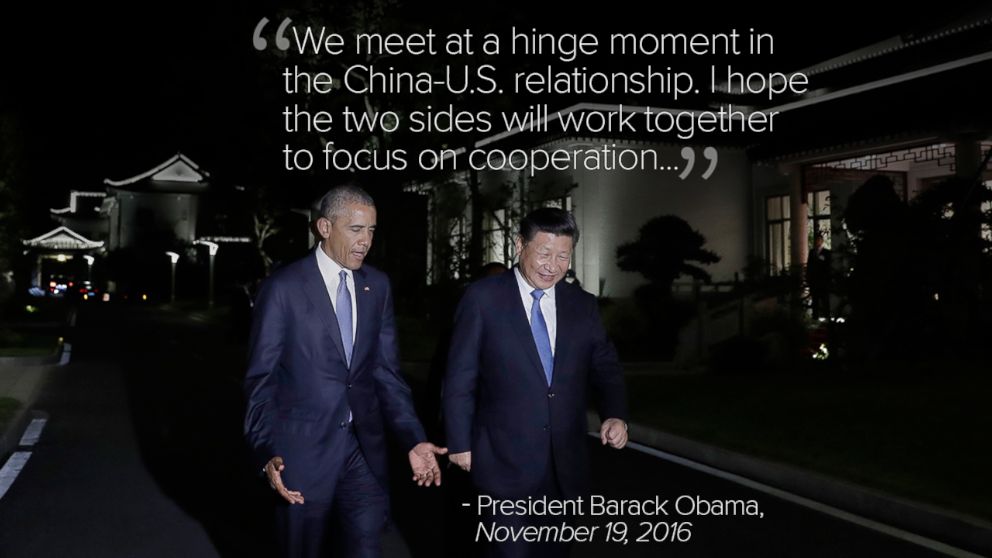

China Policy – The Unfinished Pivot

The Obama administration planned to shift the focus of foreign policy from decades of attention on the Middle East to the Asia-Pacific region.

To China’s leaders, the United States’ stated desire to maintain peace and security across the Asia-Pacific region didn’t represent an overture to improving relations. It was, they felt, reaffirmation of the long-standing U.S. policy of containment of China. Obama’s stated plan to move more U.S. military assets to the region from other parts of the world did little to assuage that interpretation.

China has responded by aggressively undertaking a program of island building in the South China Sea. Small islands and reefs have been enlarged and turned into complex military bases. Dangerous contacts between U.S. and Chinese fighter jets and naval vessels in the region have increased. China recently paraded a new missile capable of hitting targets thousands of miles from its borders, nicknamed the Guam Killer because it could reach the massive U.S. military installation at Guam.

Chinese aggression has taken other forms as well.

The United States has accused China of undertaking state-sponsored cyberwarfare against American government, military and corporate computer systems. China denies this and accuses the United States of engaging in cyberattacks against it.

Obama’s most sought-after goal in the region, the Trans-Pacific Partnership trade agreement, appears to be dead in the water.

The 12-nation agreement was designed to “promote economic growth … raise living standards … and promote transparency, good governance, and enhanced labor and environmental protections,” according to the Office of the U.S. Trade Representative.

Notably, China is not included in the agreement and has signaled only faint interest in it. But at this point, that doesn’t really matter. Trump has called the TPP “a potential disaster” and has promised the U.S will withdraw from it “on Day One” of his administration.

For all those reasons, along with a failure to engage North Korea in any meaningful way, Obama’s pivot toward a foreign policy focus on the Asia-Pacific region appears to be far from complete.

The Obama administration planned to shift the focus of foreign policy from decades of attention on the Middle East to the Asia-Pacific region.

To China’s leaders, the United States’ stated desire to maintain peace and security across the Asia-Pacific region didn’t represent an overture to improving relations. It was, they felt, reaffirmation of the long-standing U.S. policy of containment of China. Obama’s stated plan to move more U.S. military assets to the region from other parts of the world did little to assuage that interpretation.

China has responded by aggressively undertaking a program of island building in the South China Sea. Small islands and reefs have been enlarged and turned into complex military bases. Dangerous contacts between U.S. and Chinese fighter jets and naval vessels in the region have increased. China recently paraded a new missile capable of hitting targets thousands of miles from its borders, nicknamed the Guam Killer because it could reach the massive U.S. military installation at Guam.

Chinese aggression has taken other forms as well.

The United States has accused China of undertaking state-sponsored cyberwarfare against American government, military and corporate computer systems. China denies this and accuses the United States of engaging in cyberattacks against it.

Obama’s most sought-after goal in the region, the Trans-Pacific Partnership trade agreement, appears to be dead in the water.

The 12-nation agreement was designed to “promote economic growth … raise living standards … and promote transparency, good governance, and enhanced labor and environmental protections,” according to the Office of the U.S. Trade Representative.

Notably, China is not included in the agreement and has signaled only faint interest in it. But at this point, that doesn’t really matter. Trump has called the TPP “a potential disaster” and has promised the U.S will withdraw from it “on Day One” of his administration.

For all those reasons, along with a failure to engage North Korea in any meaningful way, Obama’s pivot toward a foreign policy focus on the Asia-Pacific region appears to be far from complete.

Immigration – An Unrealized Promise

As a candidate, Obama promised comprehensive immigration reform in his first year.

“I cannot guarantee that it is going to be in the first 100 days. But what I can guarantee is that we will have in the first year an immigration bill that I strongly support and that I’m promoting,” he told Univision host Jorge Ramos. But immigration was pushed to the back burner by more pressing needs.

It wasn’t until 2010 that an important step was made for thousands of undocumented immigrants. A bill was finally introduced not for overarching immigration reform but for those brought to the United States as children. The Dream Act offered a way to get right with the law, work and get on a pathway to citizenship after passing background checks and paying fees. But Congress, which did away with similar bills in 2001 and 2007, stalled. Finally, Obama took unilateral action in 2012, calling the action a “stop gap” to allow Congress to work on legislation.

In 2013 the Senate introduced a bipartisan bill to tackle the issue affecting more than 11 million lives. It would have given an additional $30 billion to border security, reformed the visa system and allowed undocumented immigrants to come out of the shadows. But then–Speaker of the House John Boehner refused to bring the legislation up for a vote after vocal opposition from a Republican minority.

A year later, with still no vote in the House, Obama again took matters into his own hands. By the end of the year, he expanded deportation relief to a larger set of people brought to the U.S. as children and to parents of American citizens. But a challenge against this action made its way to the Supreme Court, which upheld the lower court decision that it was an unconstitutional use of power.

Although Obama wanted to see immigration reform and made it a major campaign issue, not acting on it in the first year, when Democrats controlled both chambers, appeared to be a costly strategy. Using up his capital on health care reform created chasms in the Congress that could not be overcome.

As a candidate, Obama promised comprehensive immigration reform in his first year.

“I cannot guarantee that it is going to be in the first 100 days. But what I can guarantee is that we will have in the first year an immigration bill that I strongly support and that I’m promoting,” he told Univision host Jorge Ramos. But immigration was pushed to the back burner by more pressing needs.

It wasn’t until 2010 that an important step was made for thousands of undocumented immigrants. A bill was finally introduced not for overarching immigration reform but for those brought to the United States as children. The Dream Act offered a way to get right with the law, work and get on a pathway to citizenship after passing background checks and paying fees. But Congress, which did away with similar bills in 2001 and 2007, stalled. Finally, Obama took unilateral action in 2012, calling the action a “stop gap” to allow Congress to work on legislation.

In 2013 the Senate introduced a bipartisan bill to tackle the issue affecting more than 11 million lives. It would have given an additional $30 billion to border security, reformed the visa system and allowed undocumented immigrants to come out of the shadows. But then–Speaker of the House John Boehner refused to bring the legislation up for a vote after vocal opposition from a Republican minority.

A year later, with still no vote in the House, Obama again took matters into his own hands. By the end of the year, he expanded deportation relief to a larger set of people brought to the U.S. as children and to parents of American citizens. But a challenge against this action made its way to the Supreme Court, which upheld the lower court decision that it was an unconstitutional use of power.

Although Obama wanted to see immigration reform and made it a major campaign issue, not acting on it in the first year, when Democrats controlled both chambers, appeared to be a costly strategy. Using up his capital on health care reform created chasms in the Congress that could not be overcome.

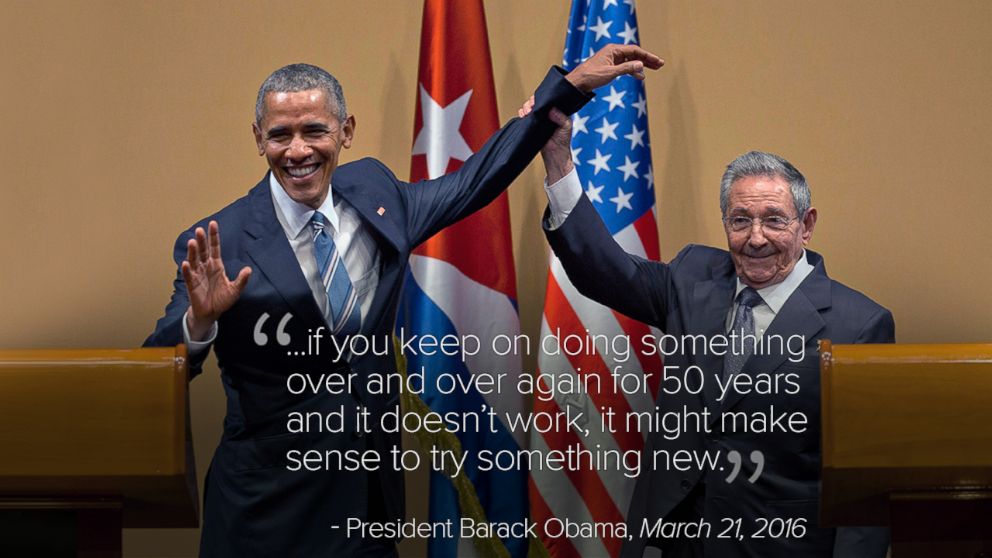

Cuba – Acknowledging a Neighbor

In 2014, Obama took an unexpected action: He opened up dialogue, negotiations and a relationship with Cuba, the island only 90 miles away from the Florida coast that had been off limits for decades.

On Dec. 17 of that year, Obama and Cuban President Raul Castro — speaking to their people at the same time from their respective capitals — announced a new way forward, pledging to reopen diplomatic channels after a prisoner exchange and the humanitarian release of U.S. contractor Alan Gross. Negotiations to accomplish this exchange and open relations between the two countries in general came at the urging of Pope Francis.

Over the next two years, the U.S. and Cuba relaxed travel restrictions, came to trade agreements, opened up commercial flights between the two countries, relaxed restrictions on cigars and rum being taken back to the U.S. for personal use and even reopened embassies.

Obama traveled to the island in March 2016 — the first time in nearly a century a sitting American president visited Cuba.

Obama told ABC’s David Muir, “I think it is very important for the United States not to view ourselves as the agents of change here but rather to encourage and facilitate Cubans themselves to bring about changes ... We want to make sure that whatever changes come about are empowering Cubans.”

Although Obama has said he worked to make the re-establishment of diplomatic ties “irreversible,” the policies he has put in place could be easily undone by the incoming administration because the moves were made through executive action and regulatory changes, the latter of which were more formal but can still be reversed. That doesn’t mean they will be. Trump has backed off the issue since the election.

In 2014, Obama took an unexpected action: He opened up dialogue, negotiations and a relationship with Cuba, the island only 90 miles away from the Florida coast that had been off limits for decades.

On Dec. 17 of that year, Obama and Cuban President Raul Castro — speaking to their people at the same time from their respective capitals — announced a new way forward, pledging to reopen diplomatic channels after a prisoner exchange and the humanitarian release of U.S. contractor Alan Gross. Negotiations to accomplish this exchange and open relations between the two countries in general came at the urging of Pope Francis.

Over the next two years, the U.S. and Cuba relaxed travel restrictions, came to trade agreements, opened up commercial flights between the two countries, relaxed restrictions on cigars and rum being taken back to the U.S. for personal use and even reopened embassies.

Obama traveled to the island in March 2016 — the first time in nearly a century a sitting American president visited Cuba.

Obama told ABC’s David Muir, “I think it is very important for the United States not to view ourselves as the agents of change here but rather to encourage and facilitate Cubans themselves to bring about changes ... We want to make sure that whatever changes come about are empowering Cubans.”

Although Obama has said he worked to make the re-establishment of diplomatic ties “irreversible,” the policies he has put in place could be easily undone by the incoming administration because the moves were made through executive action and regulatory changes, the latter of which were more formal but can still be reversed. That doesn’t mean they will be. Trump has backed off the issue since the election.

Relations With Russia – A Reset Gets Overloaded

Obama had been in office for less than two months when a State Department photo op went horribly, hilariously and presciently wrong all at the same time. Secretary of State Hillary Clinton and her Russian counterpart, Sergey Lavrov, stood in front of the cameras with a little yellow box that had a shiny red button on it. The prop was supposed to represent a deliberate effort to reset relations. In fact, the box was labeled in English with the word “reset.” But the Russian word on the box, Lavrov noted, was wrong. “Peregruzka” doesn’t mean “reset,” he pointed out. It means “overload.” For the next eight years, the plan to reset U.S.-Russian relations simply got overloaded with too many fundamental disagreements.

For a brief time it seemed a reset was possible. In March 2010, Obama and Russian President Dmitry Medvedev signed an arms agreement reducing the number of long-range nuclear-tipped missiles each nation would maintain. But Medvedev’s presidency was short-lived, and Vladimir Putin muscled his way back to power for a third term in an ethically questionable election.

Putin and Obama never saw eye to eye, literally or figuratively. Their 6-inch height difference (Putin is 5 foot 7, and Obama is 6 foot 1) provided a perfect physical metaphor for the awkward relationship the two endured.

The United States and Russia were able to work together to remove and destroy chemical weapons in Syria. But Obama’s earlier decision not to enforce his “red line” warning to Syria about using those weapons was a weak move, to Putin’s way of thinking. This event fell in the middle of a series of tit-for-tat actions between the two nations.The Russians routinely tested America’s defenses by flying military aircraft and sailing submarines deep into America’s defense zones and tested missile systems that the U.S. charged violated nonproliferation treaties.

Then in July 2013, Putin found a way to really stick it to the United States. Edward Snowden, a computer technician who had been working for a government contractor, managed to steal hundreds of thousands of pages of classified information from the National Security Agency. He skipped the country and made his way to Russia by way of Hong Kong before the U.S. knew what had happened. Putin granted Snowden political asylum in Russia, where he remains. Obama was so incensed by Putin’s move that he canceled a planned meeting the men were supposed to have in Moscow.

When Russia moved into the Ukrainian territory of Crimea in 2014 and announced it was annexing the region from the faltering Ukrainian government, the United States took the matter to the U.N. Security Council, but Russia vetoed efforts to formally declare the move illegal. The G-8 economic conference kicked Russia out of the club, and Obama dismissed Russia as a “regional power.”

Tensions flared even higher in the summer of 2014, when a surface-to-air missile destroyed Malaysia Airlines Flight 17, killing all 298 people on board. The flight had been crossing high above eastern Ukraine, about 30 miles from the border with Russia when it was brought down by a Soviet-made BUK missile.

Further angering the Obama administration, in 2015 the Russians began an airborne bombing campaign in Syria in support of President Bashar al-Assad’s regime. Russia said it wanted to work with the U.S. to end the Syrian conflict, but the two sides had wildly differing opinions on how that should be done.

Most recently, the American intelligence community accused the Russian government of waging cyberwarfare to try to influence the 2016 presidential election, though Moscow denies it.

For his part, Trump has praised Putin as “smart” and “highly respected” and a “strong leader” that he believes he can get along with. What that means for relations between the United States and Russia is unclear.

Obama had been in office for less than two months when a State Department photo op went horribly, hilariously and presciently wrong all at the same time. Secretary of State Hillary Clinton and her Russian counterpart, Sergey Lavrov, stood in front of the cameras with a little yellow box that had a shiny red button on it. The prop was supposed to represent a deliberate effort to reset relations. In fact, the box was labeled in English with the word “reset.” But the Russian word on the box, Lavrov noted, was wrong. “Peregruzka” doesn’t mean “reset,” he pointed out. It means “overload.” For the next eight years, the plan to reset U.S.-Russian relations simply got overloaded with too many fundamental disagreements.

For a brief time it seemed a reset was possible. In March 2010, Obama and Russian President Dmitry Medvedev signed an arms agreement reducing the number of long-range nuclear-tipped missiles each nation would maintain. But Medvedev’s presidency was short-lived, and Vladimir Putin muscled his way back to power for a third term in an ethically questionable election.

Putin and Obama never saw eye to eye, literally or figuratively. Their 6-inch height difference (Putin is 5 foot 7, and Obama is 6 foot 1) provided a perfect physical metaphor for the awkward relationship the two endured.

The United States and Russia were able to work together to remove and destroy chemical weapons in Syria. But Obama’s earlier decision not to enforce his “red line” warning to Syria about using those weapons was a weak move, to Putin’s way of thinking. This event fell in the middle of a series of tit-for-tat actions between the two nations.The Russians routinely tested America’s defenses by flying military aircraft and sailing submarines deep into America’s defense zones and tested missile systems that the U.S. charged violated nonproliferation treaties.

Then in July 2013, Putin found a way to really stick it to the United States. Edward Snowden, a computer technician who had been working for a government contractor, managed to steal hundreds of thousands of pages of classified information from the National Security Agency. He skipped the country and made his way to Russia by way of Hong Kong before the U.S. knew what had happened. Putin granted Snowden political asylum in Russia, where he remains. Obama was so incensed by Putin’s move that he canceled a planned meeting the men were supposed to have in Moscow.

When Russia moved into the Ukrainian territory of Crimea in 2014 and announced it was annexing the region from the faltering Ukrainian government, the United States took the matter to the U.N. Security Council, but Russia vetoed efforts to formally declare the move illegal. The G-8 economic conference kicked Russia out of the club, and Obama dismissed Russia as a “regional power.”

Tensions flared even higher in the summer of 2014, when a surface-to-air missile destroyed Malaysia Airlines Flight 17, killing all 298 people on board. The flight had been crossing high above eastern Ukraine, about 30 miles from the border with Russia when it was brought down by a Soviet-made BUK missile.

Further angering the Obama administration, in 2015 the Russians began an airborne bombing campaign in Syria in support of President Bashar al-Assad’s regime. Russia said it wanted to work with the U.S. to end the Syrian conflict, but the two sides had wildly differing opinions on how that should be done.

Most recently, the American intelligence community accused the Russian government of waging cyberwarfare to try to influence the 2016 presidential election, though Moscow denies it.

For his part, Trump has praised Putin as “smart” and “highly respected” and a “strong leader” that he believes he can get along with. What that means for relations between the United States and Russia is unclear.

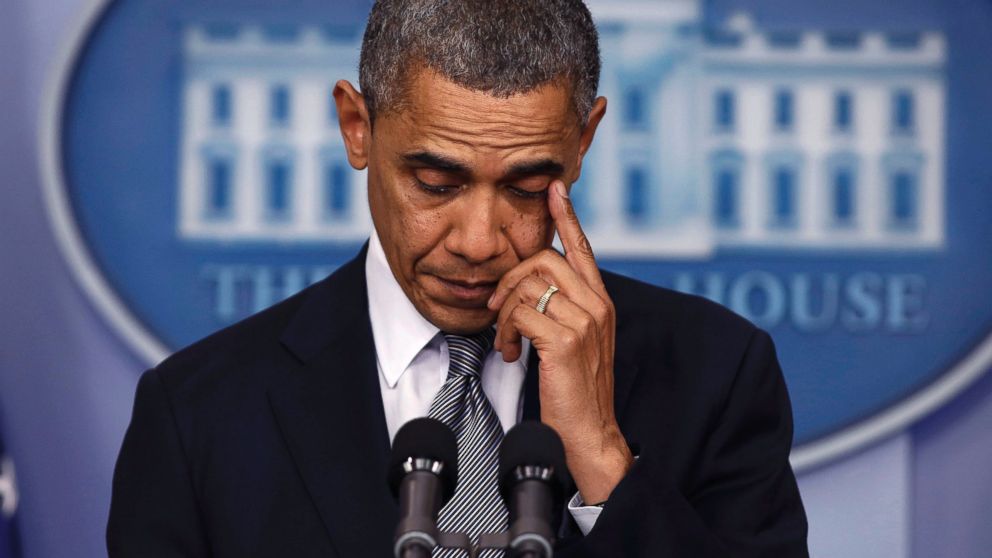

Gun Violence and Gun Control

Obama was in office less than two months when he was confronted with an issue that would dog him throughout his eight years as president. A man with a gun killed 10 people and himself in Alabama. Similar incidents would happen again and again and again.

Fourteen people were killed in Binghamton, New York, in April of 2009.

Thirteen dead and 30 injured at Fort Hood, Texas, in November of that year.

Six killed and 14 injured, including Rep. Gabrielle Giffords in Tucson, Arizona, January 2011.

Twenty-six died in the second-deadliest school shooting in U.S. history in Newtown, Connecticut, in December 2012.

Nine people killed in June of 2015 at a prayer meeting in a Charleston, South Carolina, church.

And there were more. Mass shootings of innocent victims made headlines on an almost routine basis.

Through tears and anger and even breaking into an impromptu rendition of “Amazing Grace” at the memorial service in that South Carolina church, Obama has tried in vain to push this nation toward what he calls “common-sense gun laws.” Having too few allies in Congress and facing a well-financed and dedicated opposition, no such change in federal law came about during his terms. In fact, every time the subject received a public airing, gun sales typically rose.

Although Second Amendment advocates were generally never fans of Obama’s, he cemented their opposition in April 2008 as he was campaigning for office. Speaking at a private fundraiser in San Francisco, he was talking about the economic desperation of residents in Rust Belt towns who had spent decades watching their jobs disappear.

“It’s not surprising then, they get bitter,” he empathized. But then came the phrase that would end any hope of achieving any substantial reform of gun laws during his presidency. “They cling to guns or religion or antipathy to people who aren't like them … as a way to explain their frustrations.” Although Obama went on a Rust Belt apology tour after the leaked audio made headlines, the damage was done.

Seven and half years into his presidency, Obama had made public statements about mass shootings in America a dozen times. He could no longer rein in his anger when addressing the nation after nine people were killed in October of 2015 at a community college in Roseburg, Oregon.

“There’s been another mass shooting in America,” he bluntly began his statement in the White House Press Room. As he spoke, the conjoined emotions of frustration and anger overcame him. His voice grew tense. With uncomfortably long pauses between each sentence, the president lectured the nation. “Our thoughts and prayers are not enough. It’s not enough. It does not capture the heartache and grief and anger that we should feel.“

Three months later, Obama issued a series of executive actions to strengthen the background check system for online and gun show sales, increase mental health funding and enlarge staffing for the FBI. "Congress still needs to act," he said. "Once Congress gets on board with common-sense gun safety measures, we can reduce gun violence a whole lot.”

But Capitol Hill would not be boarding that train. “Rather than focus on criminals and terrorists, he goes after the most law-abiding of citizens,” said House Speaker Paul Ryan, R-Wis. “His words and actions amount to a form of intimidation that undermines liberty.”

Obama has expressed dismay at his inability to move the debate on gun laws, telling the BBC that he finds the stymied debate “distressing” and it has left him the “most frustrated” of any issue he has faced.

Obama was in office less than two months when he was confronted with an issue that would dog him throughout his eight years as president. A man with a gun killed 10 people and himself in Alabama. Similar incidents would happen again and again and again.

Fourteen people were killed in Binghamton, New York, in April of 2009.

Thirteen dead and 30 injured at Fort Hood, Texas, in November of that year.

Six killed and 14 injured, including Rep. Gabrielle Giffords in Tucson, Arizona, January 2011.

Twenty-six died in the second-deadliest school shooting in U.S. history in Newtown, Connecticut, in December 2012.

Nine people killed in June of 2015 at a prayer meeting in a Charleston, South Carolina, church.

And there were more. Mass shootings of innocent victims made headlines on an almost routine basis.

Through tears and anger and even breaking into an impromptu rendition of “Amazing Grace” at the memorial service in that South Carolina church, Obama has tried in vain to push this nation toward what he calls “common-sense gun laws.” Having too few allies in Congress and facing a well-financed and dedicated opposition, no such change in federal law came about during his terms. In fact, every time the subject received a public airing, gun sales typically rose.

Although Second Amendment advocates were generally never fans of Obama’s, he cemented their opposition in April 2008 as he was campaigning for office. Speaking at a private fundraiser in San Francisco, he was talking about the economic desperation of residents in Rust Belt towns who had spent decades watching their jobs disappear.

“It’s not surprising then, they get bitter,” he empathized. But then came the phrase that would end any hope of achieving any substantial reform of gun laws during his presidency. “They cling to guns or religion or antipathy to people who aren't like them … as a way to explain their frustrations.” Although Obama went on a Rust Belt apology tour after the leaked audio made headlines, the damage was done.

Seven and half years into his presidency, Obama had made public statements about mass shootings in America a dozen times. He could no longer rein in his anger when addressing the nation after nine people were killed in October of 2015 at a community college in Roseburg, Oregon.

“There’s been another mass shooting in America,” he bluntly began his statement in the White House Press Room. As he spoke, the conjoined emotions of frustration and anger overcame him. His voice grew tense. With uncomfortably long pauses between each sentence, the president lectured the nation. “Our thoughts and prayers are not enough. It’s not enough. It does not capture the heartache and grief and anger that we should feel.“

Three months later, Obama issued a series of executive actions to strengthen the background check system for online and gun show sales, increase mental health funding and enlarge staffing for the FBI. "Congress still needs to act," he said. "Once Congress gets on board with common-sense gun safety measures, we can reduce gun violence a whole lot.”

But Capitol Hill would not be boarding that train. “Rather than focus on criminals and terrorists, he goes after the most law-abiding of citizens,” said House Speaker Paul Ryan, R-Wis. “His words and actions amount to a form of intimidation that undermines liberty.”

Obama has expressed dismay at his inability to move the debate on gun laws, telling the BBC that he finds the stymied debate “distressing” and it has left him the “most frustrated” of any issue he has faced.

The Reluctant Warrior – Iraq, Afghanistan and Terrorism

The United States had been at war in Iraq for nearly six years when Barack Obama became president. Thousands of U.S. troops had died there, and many Americans were wondering what all the bloodshed was for. Yes, Saddam Hussein was gone. But his capture, trial and hanging had happened years earlier. A surge of U.S. military personnel the previous year was somewhat successful, and President George W. Bush was in the process of drawing down America’s military force there. But the conflict had degenerated into a tribal battle for control of the country between Shiite and Sunni Muslims and was far from resolved.

At the same time, America was still involved in an ever-escalating conflict with the Taliban in Afghanistan. As 2008 drew to a close, the conflict had destabilized the Afghan government. More than 30,000 U.S. troops were on the ground there, and hundreds had already been killed.