An arbitrator determined a famed figure skating coach abused children. He lifted his lifetime ban anyway

Richard Callaghan has faced multiple allegations of sexual abuse.

An arbitrator who reviewed the evidence collected by the independent watchdog organization U.S. Center for SafeSport against once-celebrated figure skating coach Richard Callaghan lifted his lifetime ban from the sport despite his conclusion that Callaghan had sexually, physically and emotionally abused young skaters. The arbitrator believed he had no other choice.

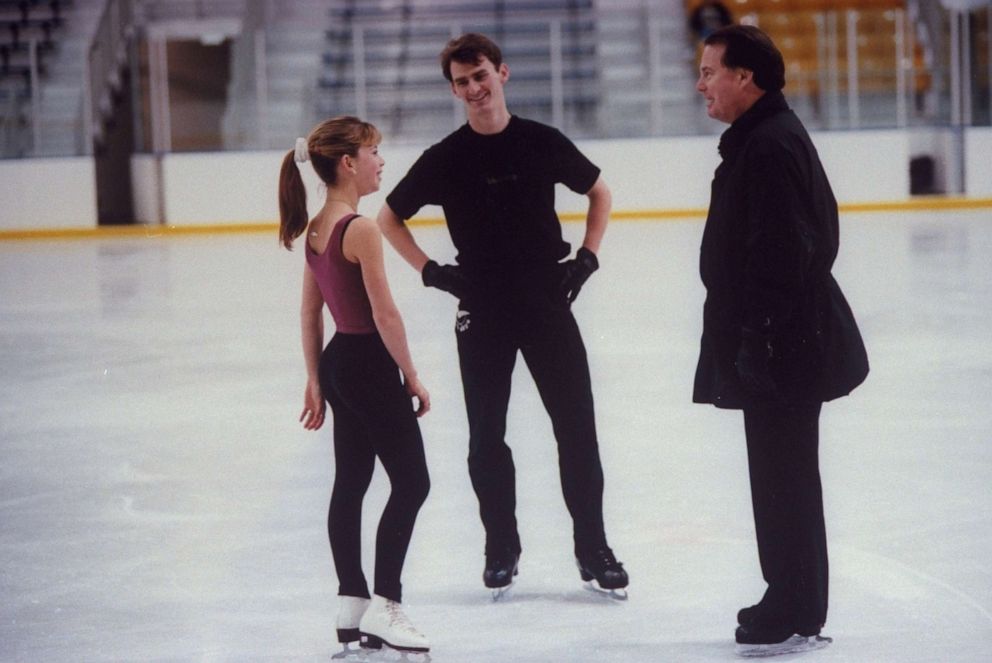

Callaghan, who has coached some of the world’s most decorated skaters, was initially banned for life in August 2019 following an 18-month investigation into his conduct sparked by allegations of sexual abuse reported to SafeSport by his former student and colleague Craig Maurizi.

Callaghan appealed that decision to an arbitrator, who lifted the ban and instead imposed a three-year suspension, 15-year probation and 100 hours of community service, making Callaghan eligible to return to the ice in 2022.

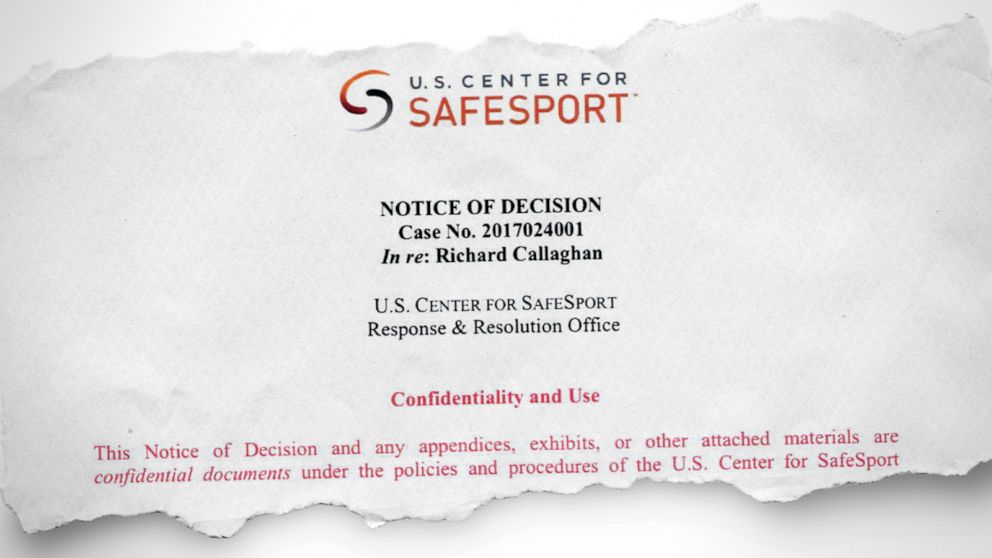

A tranche of confidential documents obtained by ABC News and ESPN reveal that SafeSport’s investigators found that Callaghan had engaged in various forms of misconduct with both male and female skaters. Callaghan’s actions, the arbitrator wrote in his hearing decision, were “deplorable and unbecoming of a coach in the Olympic movement,” adding that “sexual activity with a minor … has no place in sport.”

He decided, however, that, because procedural rules regarding conduct that preceded SafeSport’s existence dictated that he rely on the standards of that time, he applied what he called “an absurd and draconian” since-repealed law adopted in New York in 1980, which required “corroboration” for certain sexual offenses. Without a witness to, or other corroborating evidence of, the sexual abuse, in other words, his hands were tied.

“The undersigned sympathizes with Mr. Maurizi and acknowledges and agrees that his testimony confirms the sexual abuse occurred as described,” wrote the arbitrator. “However, SafeSport failed to produce corroborating evidence as required … The standard in effect at the time of the sexual acts required heightened evidence that is absurd, but that is the standard the undersigned must apply to this case. Accordingly, with regret, the undersigned finds that the conduct of Callaghan pertaining to Mr. Maurizi does not violate the [SafeSport Code for Olympic and Paralympic Movements].”

In response to questions from ABC News and ESPN, the U.S. Center for SafeSport issued a statement referring to a number of “contributing factors” that can affect the outcome of an arbitrator’s decision that are unrelated to the substance of the allegation.

“When an arbiter reduces a sanction, it should not be assumed they found that no abuse occurred, or even that the Center failed to present a thorough investigation and well-founded justification for a sanction,” the statement reads. “Contributing factors to an arbitration outcome can include trying to enforce whatever rules and laws existed at the time, prior to the SafeSport Code. In spite of those challenges, the Center is committed to ending abuse in sport and will continue to hold participants accountable.”

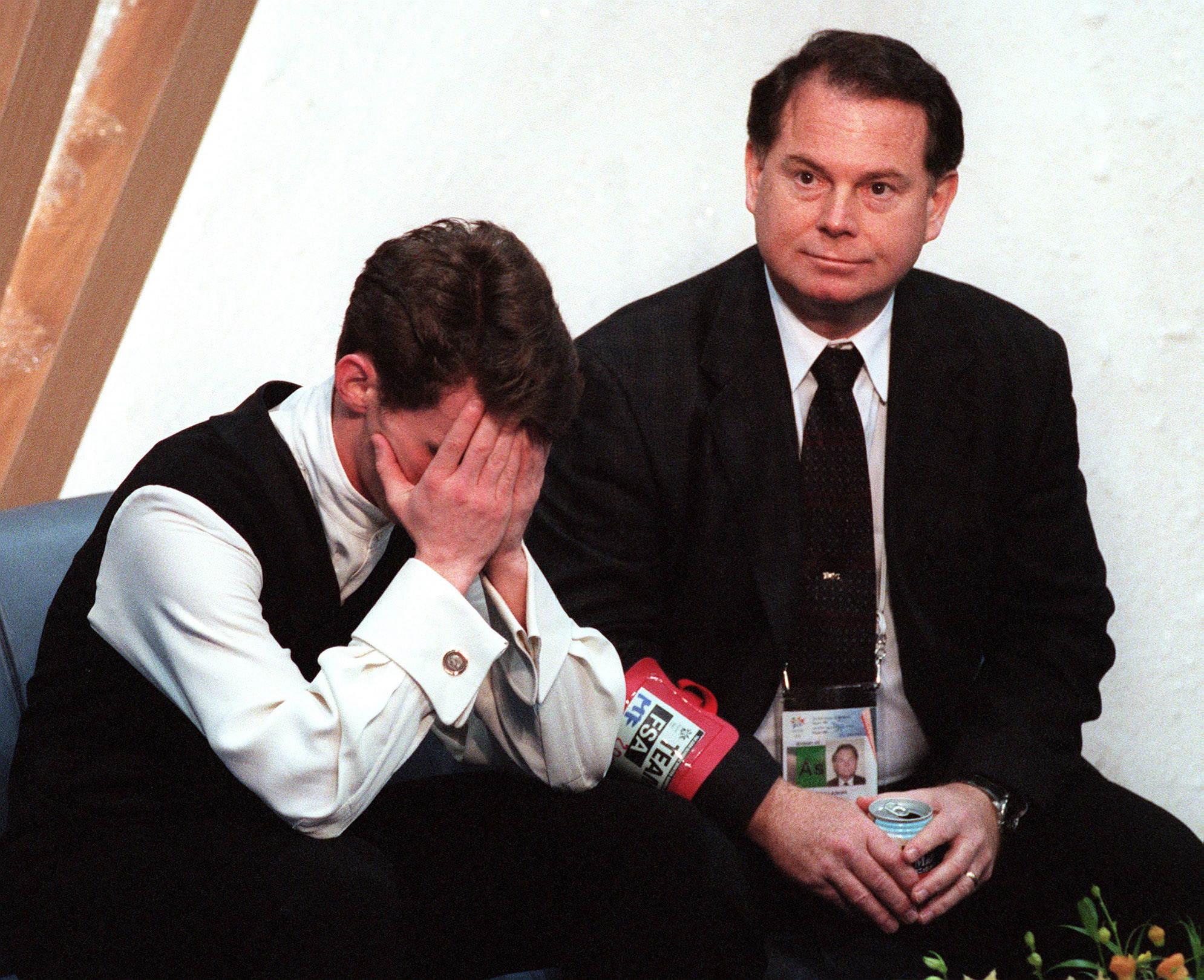

For Maurizi, 56, a former skater turned coach who first accused Callaghan in 1999 of sexually abusing him decades earlier, that decision brought a two-decade saga to a devastating conclusion.

“I’m shocked and disappointed,” Maurizi told ABC News and ESPN. “SafeSport was put in place to stop predators. But, in my case, they did just the opposite.”

Maurizi’s attorney, Ilene Jaroslaw, a partner at the New York-based firm Phillips Nizer, told ABC News and ESPN that the arbitrator’s decision contained “glaring errors” and showed a “fundamental misunderstanding of the law and a willful blindness as to the nature of Richard Callaghan’s years-long predation against my client.” SafeSport considers the arbitrator’s ruling the final word on Callaghan’s case, but Jaroslaw said her client plans to pursue other legal options.

For Callaghan, 74, who was still coaching in Florida when he was suspended by SafeSport pending further investigation, that decision opened the door to his potential return to the sport.

Callaghan is facing additional allegations of sexual abuse of a minor, which he has denied, brought in a lawsuit filed by another former student in August 2019, but his status in SafeSport’s public disciplinary database has been updated from “permanent ineligibility” to “suspension,” and “sexual misconduct” has been removed from his list of violations.

The arbitration proceedings and the investigation that preceded it are considered private and confidential, so until now its contents remained hidden from public view.

“I have put a call into SafeSport about the leak,” Dean Groulx, Callaghan’s attorney, told ABC News and ESPN. He declined to comment further.

And for the U.S. Center for SafeSport, that decision exposes a potentially serious flaw in a system that has at times struggled to maintain the trust of the athlete community it aims to serve.

SafeSport’s biggest hurdle, according to Bridgette Stumpf, executive director of Network for Victim Recovery of DC, might prove to be the one thing no one can change – the past.

“If the system in place to solve this challenge within the Olympic Movement is only given the authority to reflect back on laws from 40 years ago, the problem is going to be that many of those laws aren’t going to be very helpful for survivors,” Stumpf told ABC News and ESPN. “It’s setting up SafeSport and their arbitrators to fail.”

Maurizi has twice reported that he was sexually abused by Callaghan when he was a teenager skating for Callaghan starting in the 1970s. And twice the systems in place to handle complaints of misconduct appeared to break down.

He first accused Callaghan in 1999, filing a grievance with U.S. Figure Skating, the sport’s national governing body, that included accounts from several other people who either allegedly experienced or witnessed sexual misconduct by Callaghan. The federation quickly dismissed that grievance without full consideration, however, because skating bylaws at the time stipulated that alleged misconduct must be reported within 60 days. Callaghan was permitted to continue coaching.

Nearly two decades later, Maurizi accused Callaghan again, submitting a complaint to the newly formed U.S. Center for SafeSport, which was authorized by Congress to investigate cases on behalf of the national governing bodies under the umbrella of the U.S. Olympic and Paralympic Committee. With the aim of ending child abuse in sports, SafeSport uses a lower burden of proof than the court system and does not have a statute of limitations in an effort to oust offenders who may not be charged with crimes.

Maurizi’s case would prove to be one of the first major tests of the organization’s capabilities.

Maurizi has long maintained that the evidence of Callaghan’s misconduct was “overwhelming,” and the pair of independent lawyers hired by SafeSport to conduct the original investigation of the matter appeared to agree with him, paving the way for Callaghan’s lifetime ban from the sport.

In a 53-page report summarizing about 200 pages of evidence gathered across interviews with 17 different people, Kai McGintee and Sara Hellstedt, attorneys specializing in Title IX and workplace investigations for the Portland, Maine-based firm Bernstein Shur, outlined a litany of findings against the famed coach.

“This investigation found by a preponderance of the evidence that, over the course of two decades, [Callaghan] engaged in grooming behavior, non-contact behavior of a sexual nature, inappropriate physical contact, and sexual contact and intercourse, physical and emotional misconduct, and a pattern of exploitative and abusive conduct with young athletes he coached,” the investigators wrote.

Callaghan “used alcohol, emotional manipulation, and his position of power” to sexually abuse Maurizi from the time he was about 15 or 16 years old until he was about 22 years old, their report said, and he “engaged in a similar pattern of sexual misconduct and grooming” with several other male athletes he coached while they were in their late teens or early 20s.

Multiple female athletes, meanwhile, endured a different form of abuse. Callaghan “routinely berated” female students about their weight, investigators found, and “engaged in forceful physical contact” with female students when he was frustrated with their performance, including “pulling their hair, whacking them with a skate guard, and pushing and shaking them.”

Callaghan has repeatedly denied any misconduct, but according to investigators, the consequences of Callaghan’s misconduct were dire.

Many male athletes “suffered from ongoing drug and alcohol addiction, and had their lives irreparably damaged in ways impossible to articulate or calculate,” the investigators wrote, while some female athletes “develop[ed] long-term eating disorders” or “engage[d] in self-harm.”

It would be enough evidence for the U.S. Center for SafeSport, based on its investigators’ conclusions, to declare Callaghan “permanently ineligible” for membership in U.S. Figure Skating in August, but it would prove insufficient to keep Callaghan on the sidelines forever.

Callaghan requested an arbitration hearing to contest the sanctions, as he is permitted to do under SafeSport’s rules, which was held via videoconference on Dec. 2. Maurizi stated his case, one final time, in full view of his alleged abuser.

Even though SafeSport does not have a statute of limitations, the organization acknowledged cases involving older allegations, like Maurizi's, can be challenging to navigate.

“Allegations that predate the Center (prior to March 2017) are still heard, investigated, and when abuse is found, those who perpetrated it are held accountable,” SafeSport said in a statement. “In those matters predating the Code, the Center’s investigators apply the standards, rules and laws that existed at the time of the allegations.”

While SafeSport’s investigators asserted that Callaghan’s conduct violated various state statutes, the arbitrator provided by JAMS, a third-party arbitration body, cited an antiquated evidentiary standard that put a practically impossible burden of proof on Maurizi.

The arbitrator applied Section 130.16 of the New York Penal Law in effect 30 years ago, which stated that “a person shall not be convicted of consensual sodomy, or an attempt to commit the same, or of any offense defined in this article of which lack of consent is an element but results solely from incapacity to consent because of the alleged victim’s age, mental defect, or mental incapacity, or an attempt to commit the same, solely on the testimony of the alleged victim, unsupported by other evidence.”

As a result, he determined that despite his belief that Callaghan sexually abused Maurizi, Callaghan’s alleged sexual misconduct would not be subject to discipline, and he crafted Callaghan’s revised sanction based on other claims of physical and emotional misconduct levied by other skaters.

The arbitrator’s name is redacted in the hearing decision, but a source familiar with the matter identified him as Christian Dennie, an attorney and mediator at the Fort Worth, Texas-based sports law firm Barlow Garsek & Simon who acknowledges an affiliation with JAMS on his professional profile.

Dennie did not respond to multiple requests for comment from ABC News and ESPN. A spokesperson for JAMS said that he was “unable to comment” and referred the matter to SafeSport.

In a statement, SafeSport said that while it might not agree with this particular arbitrator’s decision, the arbitration process itself is an essential component of its operation.

“In the matter of Richard Callaghan, the Center stands behind its thorough investigation and decision to issue a lifetime ban,” SafeSport said in a statement. “Even when the Center disagrees with the outcome, it must respect the arbitration process as it is essential to maintaining fairness and SafeSport’s authority to pursue these matters.”

In the privacy of the arbitration hearing, however, SafeSport expressed more urgent concerns. The consequences of this decision, SafeSport feared, would stretch far beyond figure skating.

“SafeSport argued,” the arbitrator noted, “that Callaghan’s participation in sport puts the integrity of the Olympic Movement at risk.”

After many years of fighting, Maurizi finds himself back where he started.

He believes the decision to once again allow Callaghan to eventually return to the ice has “put kids at risk” and hopes U.S. Figure Skating will consider independently banning Callaghan from coaching again, with or without SafeSport’s support.

In response to questions from ABC News, however, U.S. Figure Skating deferred to SafeSport.

“The U.S. Center for SafeSport has exclusive jurisdiction in these matters,” the federation said in a statement. “U.S. Figure Skating is required to and will enforce all decisions of the Center.”

Lawmakers are currently deciding whether to pass a new federal law that would significantly bolster the U.S. Center for SafeSport with millions of dollars of what they say is much-needed annual funding. The new law would require the U.S. Olympic and Paralympic Committee to provide $20 million to SafeSport in each of the next five years, more than three times what the USOPC, the organization’s chief funder, currently provides.

The arbitrator’s decision to lift Callaghan’s lifetime ban, however, appears to have emboldened some of SafeSport’s fiercest critics at an inopportune moment.

John Manly, an attorney whose firm Manly, Stewart & Finaldi once represented Maurizi and now represents one of Callaghan’s other accusers – in addition to many of the victims of disgraced USA Gymnastics team doctor Larry Nassar – said the lack of authority reflected in this decision calls SafeSport’s true purpose into question. He described the organization as being too cozy with the sporting bodies it has been charged with regulating and even called for it to be defunded.

As a rule, he said, he does not recommend that any of his clients participate in investigations by SafeSport, believing it to be little more than a public relations ploy.

“All I know is, is that if you're an athlete, and you've been sexually assaulted, the last place you want to go is SafeSport,” Manly told ABC News and ESPN. “Because they're not there to protect you. They're there to protect the Olympic Movement.”

Following the publication of this report, SafeSport spokesperson Dan Hill called Manly's stance "unacceptable."

"We are disappointed in Mr. Manly’s irresponsible suggestion that victims of sexual abuse, and those who witness it, not report it to the US Center for SafeSport," Hill told ABC News and ESPN. "To encourage participants to violate the SafeSport Code by not reporting sexual abuse is unacceptable, especially as it pertains to matters involving the abuse of a minor. It is something we take seriously and are looking into. The Center has made nearly 300 individuals permanently ineligible to participate since opening its doors in 2017. We believe athlete well-being should be the highest priority in sport and that holding perpetrators accountable for abuse is essential to making that a reality."

Others suggested that lawmakers could spearhead more moderate reforms, starting with the arbitration process.

“Maybe that’s where the policy fix needs to happen,” Stumpf told ABC News and ESPN. “Give arbitrators more discretion to use more up-to-date and relevant laws in their decision making.”

Maurizi, however, has already lost his faith in the U.S. Center for SafeSport as a mechanism for holding alleged abusers accountable.

“If a situation like mine could turn out like this,” Maurizi said, “there’s a major issue with the organization.”

Pete Madden is an investigative producer for ABC News. Dan Murphy is a staff writer for ESPN.