The trail to Dead Horse Bay is easy to overlook, but Gerard Barbot knows the way.

The Brooklyn-based artist has been coming to this desolate cove on the outskirts of New York City for 25 years, and by now he can spot the trailhead with ease. Hidden behind an unassuming bus stop on the southwestern corner of Brooklyn, the unmarked path leads Barbot beneath a canopy of black cherry trees flanked by thickets of invasive reeds. Gradually, the roar of traffic on Flatbush Avenue fades to just a murmur as the earth under foot morphs into sand.

“You’d never think you’re in New York City,” Barbot told ABC News.

As the path opens onto the beach, Barbot’s footsteps are met with the crunch of rusted metal. The noise confirms he has reached his destination: Dead Horse Bay. It’s one of New York’s most mysterious and polluted sites, where half century old garbage blankets the shoreline. He passes lead batteries, sewing machines and old car parts emerging from the sand like forgotten tombstones. Waves crash to the sound of broken glass, as thousands of bottles clang against one another beneath the water’s surface.

Barbot lights a cigarette, pulls a plastic bag out of his jacket pocket, and studies the apocalyptic landscape surrounding him. The 63-year-old artist makes sculptures from found objects and Dead Horse Bay has provided him a constant stream of raw material for decades. He scours the shoreline, bending toward the sand to retrieve a rusted spoon, several marbles, a lipstick container, and a porcelain doll’s head.

“This is what we are,” Barbot said, “the results of what we are.”

Barbot knows the artifacts lining Dead Horse Bay’s shores are more than just garbage. They are the remnants of destroyed neighborhoods across the city, a half buried monument to the lives of hundreds of displaced New Yorkers, and a portal to a time when New York and the United States were undergoing a remarkable transformation.

“The truth of our lives is not always in the stories we tell but in the stories we leave behind with our stuff,” Robin Nagle, the anthropologist in residence for the New York Department of Sanitation, told ABC News.

“And lives are strewn across the beach at Dead Horse Bay,” she said.

The Brooklyn-based artist has been coming to this desolate cove on the outskirts of New York City for 25 years, and by now he can spot the trailhead with ease. Hidden behind an unassuming bus stop on the southwestern corner of Brooklyn, the unmarked path leads Barbot beneath a canopy of black cherry trees flanked by thickets of invasive reeds. Gradually, the roar of traffic on Flatbush Avenue fades to just a murmur as the earth under foot morphs into sand.

“You’d never think you’re in New York City,” Barbot told ABC News.

As the path opens onto the beach, Barbot’s footsteps are met with the crunch of rusted metal. The noise confirms he has reached his destination: Dead Horse Bay. It’s one of New York’s most mysterious and polluted sites, where half century old garbage blankets the shoreline. He passes lead batteries, sewing machines and old car parts emerging from the sand like forgotten tombstones. Waves crash to the sound of broken glass, as thousands of bottles clang against one another beneath the water’s surface.

Barbot lights a cigarette, pulls a plastic bag out of his jacket pocket, and studies the apocalyptic landscape surrounding him. The 63-year-old artist makes sculptures from found objects and Dead Horse Bay has provided him a constant stream of raw material for decades. He scours the shoreline, bending toward the sand to retrieve a rusted spoon, several marbles, a lipstick container, and a porcelain doll’s head.

“This is what we are,” Barbot said, “the results of what we are.”

Barbot knows the artifacts lining Dead Horse Bay’s shores are more than just garbage. They are the remnants of destroyed neighborhoods across the city, a half buried monument to the lives of hundreds of displaced New Yorkers, and a portal to a time when New York and the United States were undergoing a remarkable transformation.

“The truth of our lives is not always in the stories we tell but in the stories we leave behind with our stuff,” Robin Nagle, the anthropologist in residence for the New York Department of Sanitation, told ABC News.

“And lives are strewn across the beach at Dead Horse Bay,” she said.

The Power Broker’s Landfill

On a winter day in 1953, a small legion of dump trucks lurched toward the shores of Dead Horse Bay. Their cargo was collected from the remains of bulldozed neighborhoods throughout New York: children’s toys and women’s stockings, dentures and newspapers, wardrobes and sewing machines, thousands of glass bottles and countless other household items.

The remnants of these flattened homes and businesses were used as landfill, sealed in the ground, never to be seen again - or so it was thought.

The architect of this project was none other than Robert Moses, the former city parks commissioner often referred to as the most powerful unelected man in New York’s history. On Moses’ orders, the dump trucks unloaded their grim cargo onto the beach and into the sea.

Over the coming months, Moses would use the debris from destroyed homes to expand the shoreline several hundred feet out into the waters of Dead Horse Bay, providing space for what he hoped would someday become exquisite parkland for future New Yorkers.

It was the sort of eminent domain decision that would come to define Moses’ tenure as Parks Commissioner. Under his command, some neighborhoods, disproportionately those with a lower-income tax base, would be sacrificed for the greater good of the city.

For years, Moses had been razing thousands of Brooklyn homes, ‘slum clearing’ as it was known at the time, to make room for a network of highways and other reform projects he hoped to construct across the city.

“The age of spineless acceptance of deterioration and decay is over,” Moses said in a speech at Long Island University in 1954. Yet walking the shores of Dead Horse Bay today, where decay and deterioration are now the status quo, Moses’ words seem a cruel twist of fate.

Since Moses failed to have the landfill at Dead Horse Bay capped with anything other than topsoil, the garbage laid down by his workmen in 1953 has been seeping out of the land and into the surrounding waters for more than sixty years. Roller skates, nail polish bottles, and hair combs have all emerged from the sand, the ruins of sacrificed neighborhoods refusing to disappear.

“In 1953, the technology of landfill design was already sophisticated enough. It was far past dumping it, burying it and driving away,” Robin Nagle, the anthropologist in residence for the New York Sanitation Department, told ABC News.

“But for whatever reason, at Robert Moses’ behest, Dead Horse Bay was basically a bunch of household waste from homes razed for some of his construction projects, just dumped and then buried and it has been reasserting itself into the world pretty much ever since,” said Nagle, author of Picking Up, a book about the city's garbage workers.

“It’s haunted. Dead Horse Bay is haunted,” she said.

“The age of spineless acceptance of deterioration and decay is over,” Moses said in a speech at Long Island University in 1954. Yet walking the shores of Dead Horse Bay today, where decay and deterioration are now the status quo, Moses’ words seem a cruel twist of fate.

Since Moses failed to have the landfill at Dead Horse Bay capped with anything other than topsoil, the garbage laid down by his workmen in 1953 has been seeping out of the land and into the surrounding waters for more than sixty years. Roller skates, nail polish bottles, and hair combs have all emerged from the sand, the ruins of sacrificed neighborhoods refusing to disappear.

“In 1953, the technology of landfill design was already sophisticated enough. It was far past dumping it, burying it and driving away,” Robin Nagle, the anthropologist in residence for the New York Sanitation Department, told ABC News.

“But for whatever reason, at Robert Moses’ behest, Dead Horse Bay was basically a bunch of household waste from homes razed for some of his construction projects, just dumped and then buried and it has been reasserting itself into the world pretty much ever since,” said Nagle, author of Picking Up, a book about the city's garbage workers.

“It’s haunted. Dead Horse Bay is haunted,” she said.

The Island of Ill Repute

The waters of Dead Horse Bay endured a tortured history long before Moses’ trucks arrived in the 1950s.

Situated 11 miles from Manhattan, at the southwestern mouth of Jamaica Bay, the land surrounding Dead Horse Bay was once a remote island, known as Barren Island, where some of the city’s least desirable industries were housed in the mid-1800s.

Fish oil factories dried and processed hundreds of thousands of menhaden fish on the docks for use as fertilizer.

Barges filled to the brim with the city’s municipal waste were brought to Barren Island’s garbage reduction plant, the largest in the world at the time.

Other factories refined massive amounts of bat guano for fertilizer. And of course, horse rendering factories were housed on Barren Island, the last resting place for the equine creatures that made up the city’s main method of transportation.

Their carcasses, delivered by the thousands, were boiled down in gigantic vats, until the fat could be extracted and processed to make fertilizer and oil.

In the book, Fat of the Land, which chronicles the history of New York City’s garbage, author Benjamin Miller describes Barren Island as perhaps “the largest, most odorous accumulation of offal, garbage, and alienated labor in the history of the world.”

All of these noxious industries dumped their grisly by-products into the adjacent tide, giving Dead Horse Bay its ominous namesake. To this day, horse bones can still be found on its shores.

Their carcasses, delivered by the thousands, were boiled down in gigantic vats, until the fat could be extracted and processed to make fertilizer and oil.

In the book, Fat of the Land, which chronicles the history of New York City’s garbage, author Benjamin Miller describes Barren Island as perhaps “the largest, most odorous accumulation of offal, garbage, and alienated labor in the history of the world.”

All of these noxious industries dumped their grisly by-products into the adjacent tide, giving Dead Horse Bay its ominous namesake. To this day, horse bones can still be found on its shores.

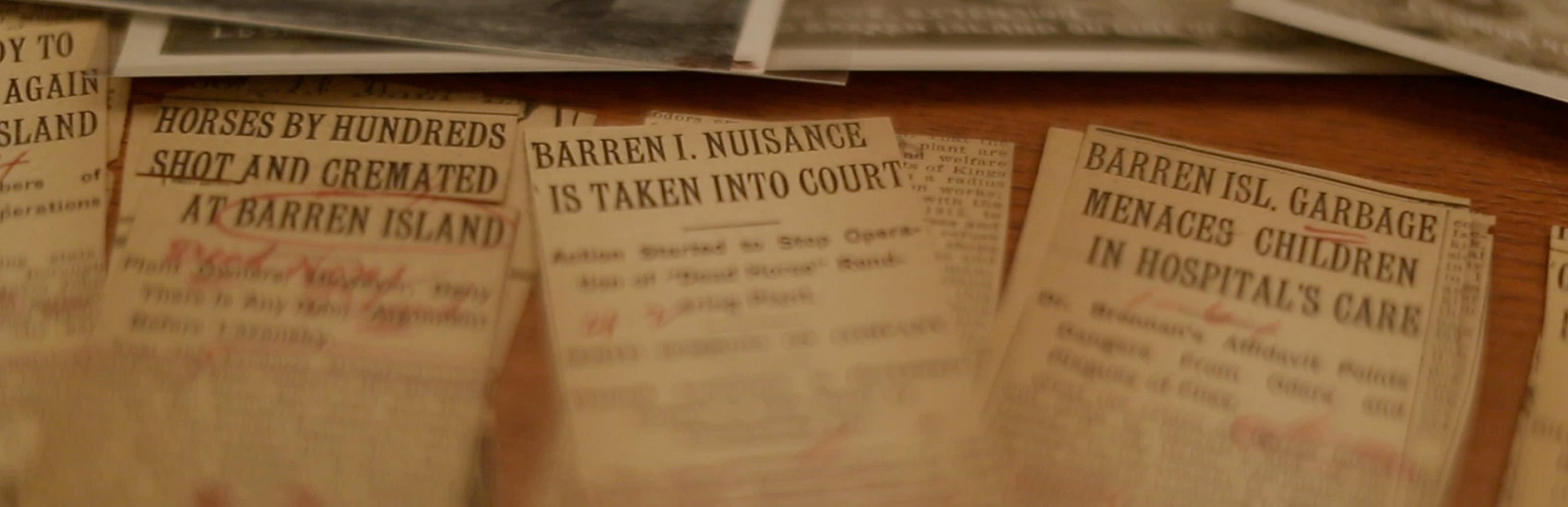

An 1891 report in the Brooklyn Daily Eagle stated that 6,942 horses, 23,765 street cats and dogs, and 184,000 pounds of fish had been processed in a single Barren Island fertilizer plant in 1889.

The Brooklyn Health Department described the powerful smell emanating from Barren Island as having “a range, flatness of trajectory and penetration equal to that of our modern coast defense rifles.”

“The smell on some unpropitious days penetrates even to the eastern confines of the city,” an Eagle reporter wrote of Barren Island on June 25, 1890.

The ‘Barren Island Nuisance,’ as it came to be known, was met with outcry from downwind residents who urged city officials to close the factories.

“At times it is impossible for us to leave our doors or windows open, owing to the vile odors carried by the wind from the factories to our dwellings. The offensive smells complained of produce sickness nausea and other and more serious discomforts,” a resident’s 1890 petition to the State Board of Health read.

The Brooklyn Health Department described the powerful smell emanating from Barren Island as having “a range, flatness of trajectory and penetration equal to that of our modern coast defense rifles.”

“The smell on some unpropitious days penetrates even to the eastern confines of the city,” an Eagle reporter wrote of Barren Island on June 25, 1890.

The ‘Barren Island Nuisance,’ as it came to be known, was met with outcry from downwind residents who urged city officials to close the factories.

“At times it is impossible for us to leave our doors or windows open, owing to the vile odors carried by the wind from the factories to our dwellings. The offensive smells complained of produce sickness nausea and other and more serious discomforts,” a resident’s 1890 petition to the State Board of Health read.

Barren Island was home to about 2000 people, and included several saloons and a one-room school house, according to Brooklyn Daily Eagle reports from the time. One young teacher was quoted in an August 18, 1901, report as saying, “some of us tried living down here last summer but we gave it up in disgust.”

The case of the Barren Island Nuisance was eventually brought before a grand jury, where one Sheepshead Bay resident testified that “one smell would produce headache in three minutes,” according to the paper.

The nuisance even ensnared Theodore Roosevelt, the then-Governor of New York, who visited the island and promised to rid it of its noxious industries, calling their odors “a nuisance of the worst kind,” according to a May 9, 1899 Brooklyn Daily Eagle article.

The factories were eventually shuttered after a prolonged legal battle. By the 1930s, Barren Island was connected to the rest of Brooklyn to make room for the city’s first municipal airport, Floyd Bennett Field. More than 40 years later, in 1972, the bay was acquired by the federal government as part of the Gateway National Recreation Area.

At long last, Moses had his park, though by then he had retired from city government.

The case of the Barren Island Nuisance was eventually brought before a grand jury, where one Sheepshead Bay resident testified that “one smell would produce headache in three minutes,” according to the paper.

The nuisance even ensnared Theodore Roosevelt, the then-Governor of New York, who visited the island and promised to rid it of its noxious industries, calling their odors “a nuisance of the worst kind,” according to a May 9, 1899 Brooklyn Daily Eagle article.

The factories were eventually shuttered after a prolonged legal battle. By the 1930s, Barren Island was connected to the rest of Brooklyn to make room for the city’s first municipal airport, Floyd Bennett Field. More than 40 years later, in 1972, the bay was acquired by the federal government as part of the Gateway National Recreation Area.

At long last, Moses had his park, though by then he had retired from city government.

A Feud Among Garbage Lovers

Today, thanks to Robert Moses’ poorly constructed landfill, a walk along the shores of Dead Horse Bay is a far cry from the pristine park both he and the National Park service might have imagined for the site. A dystopic blanket made up of dentures, women’s nylons, and broken glass bottles cover the shoreline.

“It was a site of human tragedy. All of these artifacts tell a story about the tragedy people had to go through when New York City and the United States were going through such change,” Howard Warren, a retired science teacher who took his students to Dead Horse Bay for nearly thirty years, told ABC News.

“When you take a step you’re walking on history,” Warren said.

Howard Warren, along with his fourth grade students, worked for decades to establish a comprehensive collection of Dead Horse Bay artifacts. Inside the halls of Manhattan’s Trinity School, a private K-12 school on the Upper West Side, hundreds of household objects collected from Dead Horse Bay are displayed on shelves against the wall outside Warren’s former classroom, carefully researched, labeled and displayed by his former students.

Dozens of brittle newspapers, all dated between February and March of 1953, are kept in a box in the classroom closet where visitors can also find prescription bottles with listed addresses connecting the debris to flattened neighborhoods across New York.

“It’s a graveyard of things that people held so close to them in their homes,” Warren said before adding, “it made up a quilt of their lives.”

But to Howard’s dismay, he isn’t the only person unearthing Dead Horse Bay’s forgotten treasures.

Dozens of artists and antique collectors scour the beach every year, looking for that perfect relic to add to sculptures, paintings and mantel piece collections.

“Local artists have taken artifacts from the bay and made these pieces, sculptures, that are rich with artifacts to their studios and their homes and they’re gone,” Warren told ABC News.

“There is a layer of history that is being stolen away from us,” he said.

The popularity of treasure picking at Dead Horse Bay has given rise to an unusual debate over what to do with its garbage-covered beaches. Under federal law, it is illegal to remove anything, including decaying and toxic garbage, from Dead Horse Bay, because the area is part of a protected national park.

“We’re also tasked with preserving and protecting the waters under our control,” said Lincoln Hallowell, a park ranger with the Gateway National Recreation Area. “So where is that balance? How do we explain to the public we’re protecting historic trash?”

It took several meetings with park service officials before Howard Warren and his students were finally allowed to remove items from the bay. Howard says his methods abide by archaeological standards and the treasure pickers do not have the same discipline. Treasure pickers often question the rules, claiming their efforts are inadvertently cleaning the beach, one decaying artifact at a time.

“My feeling is that because it’s a dump, it’s a landfill, and it’s garbage, so if anything I’m doing beach cleanup,” Gerard Barbot, an artist who has been accumulating artifacts from Dead Horse Bay for 25 years, told ABC News.

“It’s a graveyard of things that people held so close to them in their homes,” Warren said before adding, “it made up a quilt of their lives.”

But to Howard’s dismay, he isn’t the only person unearthing Dead Horse Bay’s forgotten treasures.

Dozens of artists and antique collectors scour the beach every year, looking for that perfect relic to add to sculptures, paintings and mantel piece collections.

“Local artists have taken artifacts from the bay and made these pieces, sculptures, that are rich with artifacts to their studios and their homes and they’re gone,” Warren told ABC News.

“There is a layer of history that is being stolen away from us,” he said.

The popularity of treasure picking at Dead Horse Bay has given rise to an unusual debate over what to do with its garbage-covered beaches. Under federal law, it is illegal to remove anything, including decaying and toxic garbage, from Dead Horse Bay, because the area is part of a protected national park.

“We’re also tasked with preserving and protecting the waters under our control,” said Lincoln Hallowell, a park ranger with the Gateway National Recreation Area. “So where is that balance? How do we explain to the public we’re protecting historic trash?”

It took several meetings with park service officials before Howard Warren and his students were finally allowed to remove items from the bay. Howard says his methods abide by archaeological standards and the treasure pickers do not have the same discipline. Treasure pickers often question the rules, claiming their efforts are inadvertently cleaning the beach, one decaying artifact at a time.

“My feeling is that because it’s a dump, it’s a landfill, and it’s garbage, so if anything I’m doing beach cleanup,” Gerard Barbot, an artist who has been accumulating artifacts from Dead Horse Bay for 25 years, told ABC News.

Barbot keeps an enormous collection of Dead Horse Bay artifacts inside a cramped basement studio in nearby Sheepshead Bay. Among his collection, one can find drawers filled with dolls heads, toy soldiers, lipstick canisters and row upon row of glass bottles.

“It’s like a bowerbird that gets all these similar colored objects, and shotgun shells, and bits of plastic, and builds a nest to attract a female,” Barbot told ABC News.

“It seems like I do that, I accumulate these things. I don’t know why though. I don’t think it’s just to attract a female. Cause most of them find it dirty or disgusting. Junk, they see junk. When it’s finished and it’s on the wall they see art,” he said.

Barbot often welds the pieces he collects at Dead Horse Bay with other found objects to make sculptures and assemblages. He’s constructed wind chimes out of gear wheels, face masks out of old car parts and dozens of small cages out of rusted and torn metal, often placing a toy figurine in the center. The results can be playfully haunting, like something out of a child’s nightmare.

“The whole idea is transforming- -- you know, what’s that old saying that one person’s trash is another’s treasure? I want ‘em to realize its junk, but look at it now,” Barbot, whose work has been exhibited around the city, told ABC News.

“It’s like a bowerbird that gets all these similar colored objects, and shotgun shells, and bits of plastic, and builds a nest to attract a female,” Barbot told ABC News.

“It seems like I do that, I accumulate these things. I don’t know why though. I don’t think it’s just to attract a female. Cause most of them find it dirty or disgusting. Junk, they see junk. When it’s finished and it’s on the wall they see art,” he said.

Barbot often welds the pieces he collects at Dead Horse Bay with other found objects to make sculptures and assemblages. He’s constructed wind chimes out of gear wheels, face masks out of old car parts and dozens of small cages out of rusted and torn metal, often placing a toy figurine in the center. The results can be playfully haunting, like something out of a child’s nightmare.

“The whole idea is transforming- -- you know, what’s that old saying that one person’s trash is another’s treasure? I want ‘em to realize its junk, but look at it now,” Barbot, whose work has been exhibited around the city, told ABC News.

Other artists who visit Dead Horse Bay are equally fascinated by the beach and frustrated by the government’s policy of banning the removal of any artifacts from the bay. Mark Batelli has been visiting the area for four years and has made numerous works from his findings, which he sells online and at flea markets around Brooklyn.

“The amount of garbage and objects taken from the beach adds up to an accumulative cleanup effort,” Batelli told ABC News before adding, “to try and prevent efforts like that is shooting yourself in the foot when it comes to a government policy.”

Since the artifacts that treasure pickers glean from the beach are just the tip of a massive landfill beneath Dead Horse Bay, it's difficult to consider their efforts a true beach cleanup.

“The amount of garbage and objects taken from the beach adds up to an accumulative cleanup effort,” Batelli told ABC News before adding, “to try and prevent efforts like that is shooting yourself in the foot when it comes to a government policy.”

Since the artifacts that treasure pickers glean from the beach are just the tip of a massive landfill beneath Dead Horse Bay, it's difficult to consider their efforts a true beach cleanup.

But Maxwell Cohen, a retired biologist who conducts tours of Dead Horse Bay for the American Littoral Society, says leaving half century old garbage on the beach in any quantity is still dangerous for wildlife.

“The waters of Dead Horse Bay are extremely contaminated,” Cohen told ABC News.

“Old storage batteries in huge numbers are still leaching the contents of those batteries. That is lead is leaching into these waters,” he said.

Cohen, who is 88-years old, grew up in nearby Rockaway Beach. As a teenager in the 1940s, he came to Dead Horse Bay to collect praying mantis eggs and fell in love with the young maritime forest that was beginning to take root. Today, he uses the beach as an example of how natural places can be degraded if they are not properly cared for.

“You don’t have to give a lecture out there, you just bring people out there and they get the message instantly,” Cohen said.

“The waters of Dead Horse Bay are extremely contaminated,” Cohen told ABC News.

“Old storage batteries in huge numbers are still leaching the contents of those batteries. That is lead is leaching into these waters,” he said.

Cohen, who is 88-years old, grew up in nearby Rockaway Beach. As a teenager in the 1940s, he came to Dead Horse Bay to collect praying mantis eggs and fell in love with the young maritime forest that was beginning to take root. Today, he uses the beach as an example of how natural places can be degraded if they are not properly cared for.

“You don’t have to give a lecture out there, you just bring people out there and they get the message instantly,” Cohen said.

It’s common to see dead sea life along the shores of Dead Horse Bay. The decaying carcasses of skates, water fowl, small sharks, and horseshoe crabs can be found washing in the tide. Gateway National Recreation Area told ABC News that they routinely test the water quality of Dead Horse Bay, though the agency did not respond to repeated requests to share the results of these tests.

“If an analysis has taken place, it’s been done on a severely limited basis and it should be done in a more detailed basis, so that we could take some sort of restorative action and pave the way for Dead Horse Bay to be restored to a more natural situation,” Maxwell Cohen told ABC News.

Underfunded and faced with a complex ecology, Gateway officials say there are no cleanup plans for Dead Horse Bay.

“If an analysis has taken place, it’s been done on a severely limited basis and it should be done in a more detailed basis, so that we could take some sort of restorative action and pave the way for Dead Horse Bay to be restored to a more natural situation,” Maxwell Cohen told ABC News.

Underfunded and faced with a complex ecology, Gateway officials say there are no cleanup plans for Dead Horse Bay.

Robin Nagle, the anthropologist in residence for the New York City Sanitation Department, points to London as an example of a potential solution, where treasure hunters are encouraged to scavenge along the foreshore of the River Thames. Collectors there are free to bring their loot home but are also incentivized to donate their findings to a local history museum. In a sense, it’s crowd-sourced archeology that also cleans the shores.

“That’s sort of a lovely and creative way to solve the problem of what do we do with stuff at Dead Horse Bay,” Nagle said.

For treasure pickers and academics alike, one thing is certain: Dead Horse Bay is among the last places in New York to see the city’s garbage. Since 2001, one hundred percent of New York City’s garbage is exported outside city limits. The local landfills have all been closed, often converted into parks or golf courses, and the city’s waste is now trucked and shipped off to far-flung places across the country and around the globe, creating one of the biggest waste displacement gaps in the world.

So far, no cultural or historical institution has formed an official relationship with Dead Horse Bay as its historic artifacts continue to disappear into the tide. The bay, like the evicted residents who shaped it, remains largely forgotten.

“People need to care about Dead Horse Bay because we are there, ourselves, our own very recent past is strewn across the beach,” Robin Nagle said.

“The people who preceded us here in the city, who helped craft and build the city from the street level, their lives are strewn across the beach at Dead Horse Bay and when we go there and walk amongst the ruins that were their material selves, their homes, the almost endless inventory of intimate objects that populate their lives, that’s what’s on the beach. And if we care about ourselves and our history, recent and long ago, we have to care about Dead Horse Bay.

It’s reflecting us back at ourselves,” she said.

“That’s sort of a lovely and creative way to solve the problem of what do we do with stuff at Dead Horse Bay,” Nagle said.

For treasure pickers and academics alike, one thing is certain: Dead Horse Bay is among the last places in New York to see the city’s garbage. Since 2001, one hundred percent of New York City’s garbage is exported outside city limits. The local landfills have all been closed, often converted into parks or golf courses, and the city’s waste is now trucked and shipped off to far-flung places across the country and around the globe, creating one of the biggest waste displacement gaps in the world.

So far, no cultural or historical institution has formed an official relationship with Dead Horse Bay as its historic artifacts continue to disappear into the tide. The bay, like the evicted residents who shaped it, remains largely forgotten.

“People need to care about Dead Horse Bay because we are there, ourselves, our own very recent past is strewn across the beach,” Robin Nagle said.

“The people who preceded us here in the city, who helped craft and build the city from the street level, their lives are strewn across the beach at Dead Horse Bay and when we go there and walk amongst the ruins that were their material selves, their homes, the almost endless inventory of intimate objects that populate their lives, that’s what’s on the beach. And if we care about ourselves and our history, recent and long ago, we have to care about Dead Horse Bay.

It’s reflecting us back at ourselves,” she said.

Published on October 26, 2015

Additional Credits

Video Editors EVAN SIMON, LUIS YORDAN, BEN SCHELLPFEFFER

Executive Producer DAN SILVER

Managing Editor XANA O'NEILL

Supervising Producer RONNIE POLIDORO

Creative Director HAL ARONOW-THEIL

Animator JASMINE BATISTE

Creative Design Director LORI NEUHARDT

Senior Developer GREG ATRIA

Additional Producer LOUISE DEWAST

Additional Credits

Video Editors EVAN SIMON, LUIS YORDAN, BEN SCHELLPFEFFER

Executive Producer DAN SILVER

Managing Editor XANA O'NEILL

Supervising Producer RONNIE POLIDORO

Creative Director HAL ARONOW-THEIL

Animator JASMINE BATISTE

Creative Design Director LORI NEUHARDT

Senior Developer GREG ATRIA

Additional Producer LOUISE DEWAST