Each weekday afternoon, a group of retirees gathers on the lawn of 71-year-old Flowers White.

They sit perched on plastic folding chairs, passing around an oversized bag of peanuts – leisurely cracking the shells and casting them onto the lawn – as the conversation meanders from car repairs to national politics to the latest football scandal.

Today, the air is thick with the sound of cicadas and the sweltering August midday sun is beating down. The men take sips from bottled water and cans of V8 as members of their crew assemble.

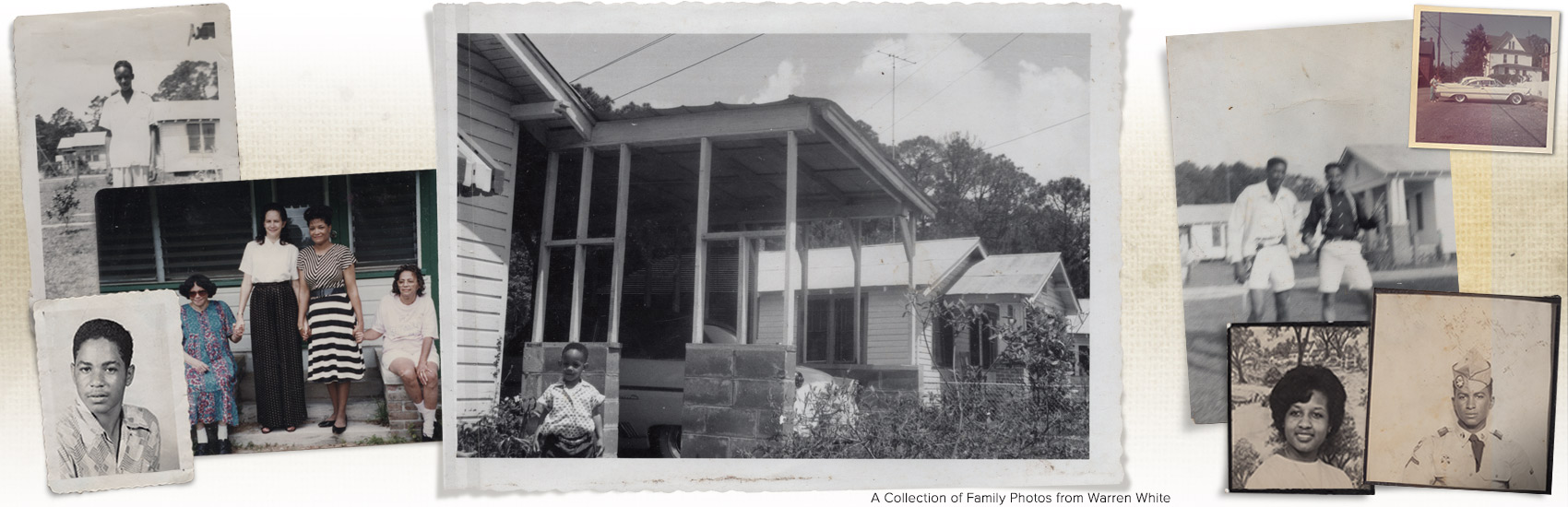

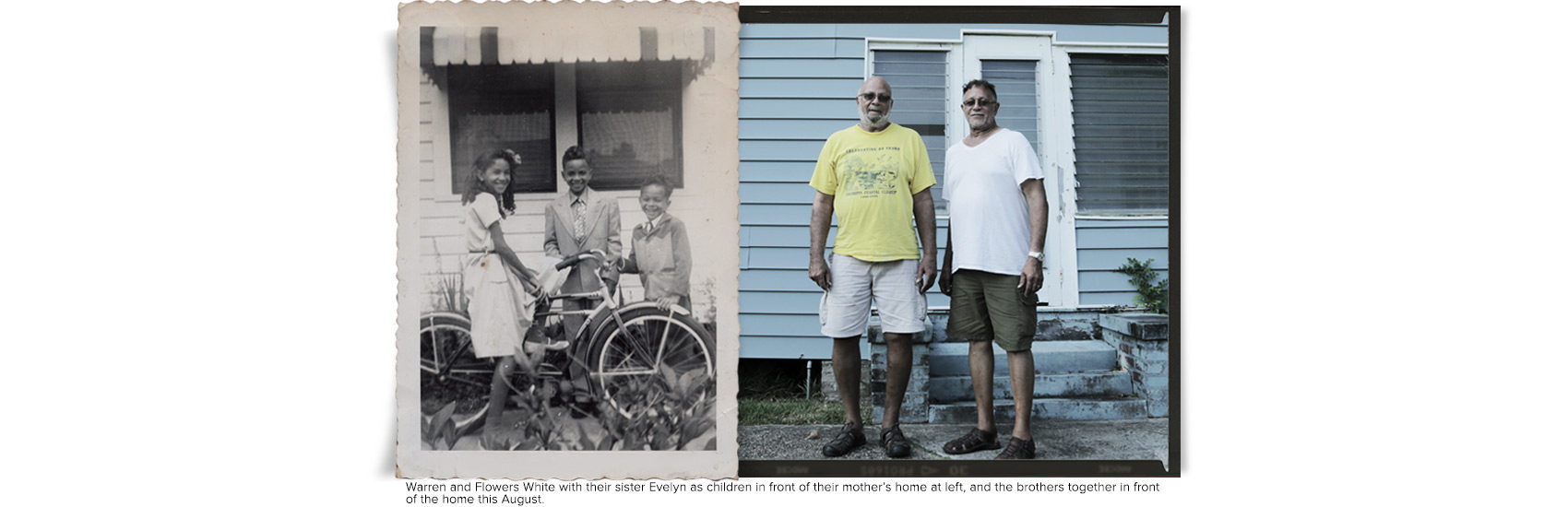

Flowers White is the host of this daily summit. He is one of the old-timers here. From his lawn, he can point out the house he was born in. His family helped found this town in 1866 – they were among the emancipated slaves who pooled their money and bought the land now known as Turkey Creek.

Turkey Creek, Mississippi became a homing beacon for following generations. Residents will tell you that everyone here is family.

On lethargic days like today, it’s hard to imagine the chaos that ripped through this sleepy town 10 years ago – when Hurricane Katrina transformed the town’s eponymous creek into a rageful river that tore through historic homes and put residents’ lives in peril.

Turkey Creek, Mississippi became a homing beacon for following generations. Residents will tell you that everyone here is family.

On lethargic days like today, it’s hard to imagine the chaos that ripped through this sleepy town 10 years ago – when Hurricane Katrina transformed the town’s eponymous creek into a rageful river that tore through historic homes and put residents’ lives in peril.

“I guess Katrina was that perfect storm that they were talking about,” Flowers’ younger brother Warren White, 69, said.

“I got lost,” he said of driving around the area. “I’ve lived here all my life and I got lost. … There were no landmarks! There was nothing to let you know where you were! And I’ve never been lost in my own communities before.”

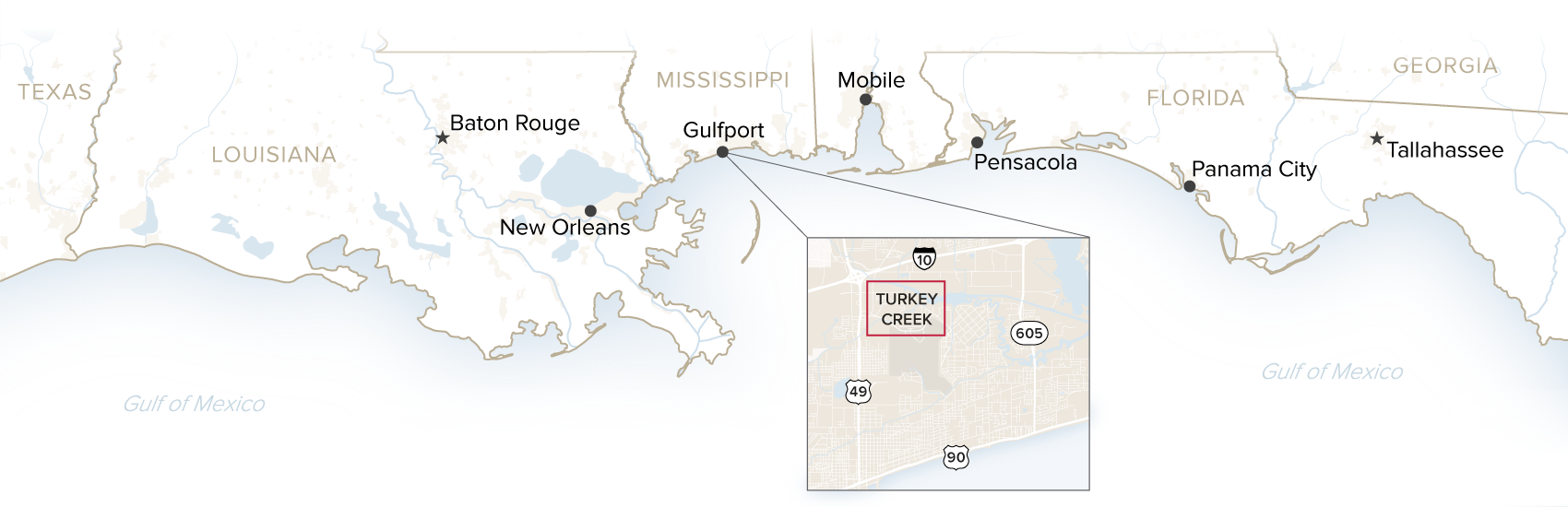

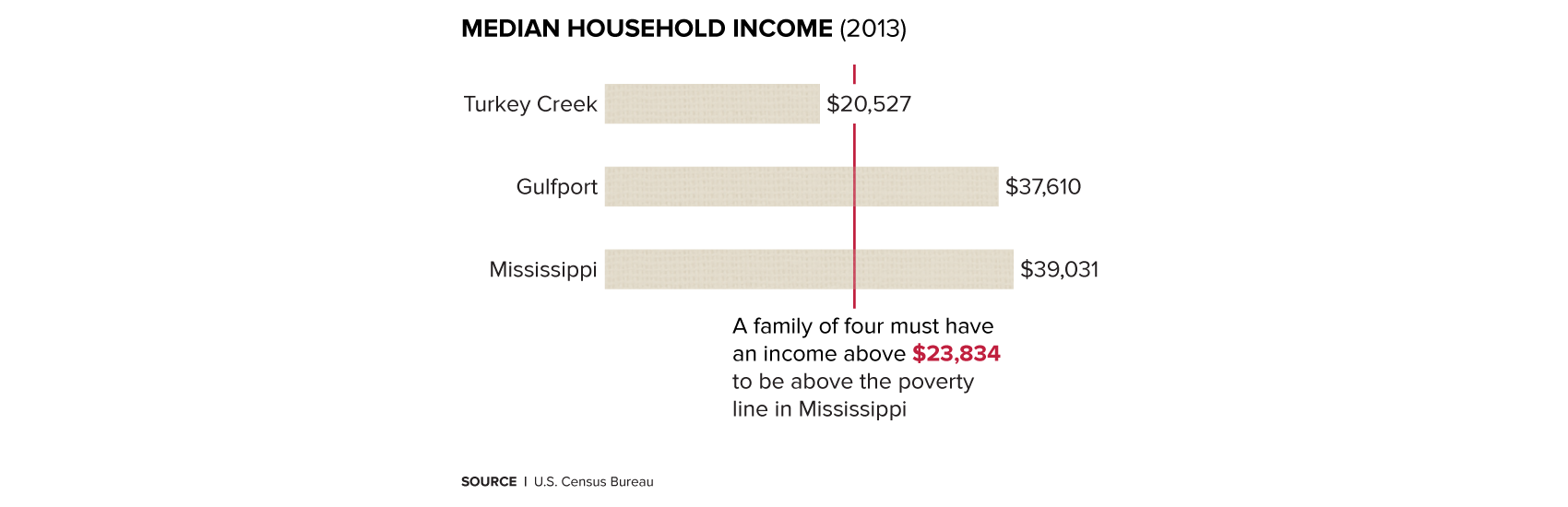

Turkey Creek, with a population local experts believe is close to 300, stands in stark contrast to its surrounding city of Gulfport.

Gulfport’s main drag is Highway 49, a four mile-long stretch which includes some short-term hotels, pawn shops and fast food restaurants; Turkey Creek’s thoroughfare is Rippy Road, a two-lane road dotted with modest homes and tidy lawns named after one of the town’s founding families.

The honking on Rippy Road comes from drivers who recognize neighbors out on their front porches, and is always accompanied by a wave.

“I got lost,” he said of driving around the area. “I’ve lived here all my life and I got lost. … There were no landmarks! There was nothing to let you know where you were! And I’ve never been lost in my own communities before.”

Turkey Creek, with a population local experts believe is close to 300, stands in stark contrast to its surrounding city of Gulfport.

Gulfport’s main drag is Highway 49, a four mile-long stretch which includes some short-term hotels, pawn shops and fast food restaurants; Turkey Creek’s thoroughfare is Rippy Road, a two-lane road dotted with modest homes and tidy lawns named after one of the town’s founding families.

The honking on Rippy Road comes from drivers who recognize neighbors out on their front porches, and is always accompanied by a wave.

John Pittman, 67, sits casually on his folding chair, alternating between crossing his arms on his chest and adjusting his cane or glasses.

“We had some old man told us some day the Gulf and Gulfport Lake are going to meet— and it did at Katrina,” Flowers White told ABC News in early August.

Pittman didn’t miss a beat. “It met at my house,” he said.

He was the hardest-hit member of the peanut-eating crew. He, like many of the residents, decided to ride out Katrina in Turkey Creek. He went to the second floor of his two-story home and started reading The Da Vinci Code.

He made three trips downstairs, watching as the water crept from his neighbor’s backyard toward his. It wasn’t long before the water reached waist height.

At one point, Pittman said he heard someone yelling and looked out the window at the house across the street.

“This guy is standing on the front porch, his daughter - they’ve kicked the door out of the attic on the front and his daughter and her husband are hanging out of there and he’s standing on the porch almost chest deep in the water, yelling ‘Help!’” Pittman said.

“We had some old man told us some day the Gulf and Gulfport Lake are going to meet— and it did at Katrina,” Flowers White told ABC News in early August.

Pittman didn’t miss a beat. “It met at my house,” he said.

He was the hardest-hit member of the peanut-eating crew. He, like many of the residents, decided to ride out Katrina in Turkey Creek. He went to the second floor of his two-story home and started reading The Da Vinci Code.

He made three trips downstairs, watching as the water crept from his neighbor’s backyard toward his. It wasn’t long before the water reached waist height.

At one point, Pittman said he heard someone yelling and looked out the window at the house across the street.

“This guy is standing on the front porch, his daughter - they’ve kicked the door out of the attic on the front and his daughter and her husband are hanging out of there and he’s standing on the porch almost chest deep in the water, yelling ‘Help!’” Pittman said.

Pittman went downstairs, waded through the waist-deep water that filled his first floor before going out the front door and jumping in the water filling the street, that had risen to be eight or nine feet.

He said that he used the utility pole and young oak tree in the front of his house as visual markers when he swam toward that family, because so much of his house and driveway was covered.

He grabbed their plastic baby crib, turning it into a flotation device to help transport the group back to the upstairs of his home that remained dry. It was his first trip of the night.

It turned out that Pittman’s elderly neighbors were also riding out the storm in their squat red brick house.

“So we went back over and sure enough Mr. and Mrs. Caldwell were sitting in their living room, in the water, very calmly and we had to get them over to my house too,” Pittman said.

In all, Pittman ended up with nine people, ranging in age from the toddler across the street to Mr. Caldwell who “had already hit 90 by then” riding out the storm in the upstairs bedrooms in his home.

About three quarters of a mile away, 26-year-old Da Shawn Thompson started weaving through the debris on the street to check on his aunt and her family after his mom received a call saying that they were getting water in their house.

“On the way, I could remember trees falling in the street… a tree fell in front of me but it didn’t stop me,” Thompson said, “So when I finally did make it to her house I noticed that her house had water in it and it was to the point where I was telling them ‘Y’all can’t stay here, y’all need to get out!’”

Thompson said his aunt was asleep, taking a nap, when he arrived at the home and he woke her to get her moving.

He said that he used the utility pole and young oak tree in the front of his house as visual markers when he swam toward that family, because so much of his house and driveway was covered.

He grabbed their plastic baby crib, turning it into a flotation device to help transport the group back to the upstairs of his home that remained dry. It was his first trip of the night.

It turned out that Pittman’s elderly neighbors were also riding out the storm in their squat red brick house.

“So we went back over and sure enough Mr. and Mrs. Caldwell were sitting in their living room, in the water, very calmly and we had to get them over to my house too,” Pittman said.

In all, Pittman ended up with nine people, ranging in age from the toddler across the street to Mr. Caldwell who “had already hit 90 by then” riding out the storm in the upstairs bedrooms in his home.

About three quarters of a mile away, 26-year-old Da Shawn Thompson started weaving through the debris on the street to check on his aunt and her family after his mom received a call saying that they were getting water in their house.

“On the way, I could remember trees falling in the street… a tree fell in front of me but it didn’t stop me,” Thompson said, “So when I finally did make it to her house I noticed that her house had water in it and it was to the point where I was telling them ‘Y’all can’t stay here, y’all need to get out!’”

Thompson said his aunt was asleep, taking a nap, when he arrived at the home and he woke her to get her moving.

His aunt, Urcell Stewart Idom, said she feared for her life.

“I just felt like I was going to drown!” she said.

“My den furniture was… floating in the water. And I was so confused, because I was like ‘Who put the furniture up there?’ I was just trying to figure it out. It was just so unreal.”

Thompson said he and a group of other young men started going door to door to check on neighbors. “[We were] trying to see who’s in there and seeing what we could do to save them,” he said.

Joshua McLaurin, 41, became part of the make-shift rescue crew. He is married to Urcell Stewart Idom’s daughter and was at his in-law’s house when Thompson first went over to check on them during the storm.

“We were actually stepping on cars because we couldn’t see them,” McLaurin said. “It was like stepping on the roofs of the cars, going over fences.”

All told, Thompson and McLaurin and the other men that banded together reportedly helped bring close to two dozen people from their flooded homes in Turkey Creek to the local church or relatives’ homes in higher parts of the neighborhood.

“I just felt like I was going to drown!” she said.

“My den furniture was… floating in the water. And I was so confused, because I was like ‘Who put the furniture up there?’ I was just trying to figure it out. It was just so unreal.”

Thompson said he and a group of other young men started going door to door to check on neighbors. “[We were] trying to see who’s in there and seeing what we could do to save them,” he said.

Joshua McLaurin, 41, became part of the make-shift rescue crew. He is married to Urcell Stewart Idom’s daughter and was at his in-law’s house when Thompson first went over to check on them during the storm.

“We were actually stepping on cars because we couldn’t see them,” McLaurin said. “It was like stepping on the roofs of the cars, going over fences.”

All told, Thompson and McLaurin and the other men that banded together reportedly helped bring close to two dozen people from their flooded homes in Turkey Creek to the local church or relatives’ homes in higher parts of the neighborhood.

After Katrina had passed through Turkey Creek, they faced the confusion of what to do about storm-ravaged homes and tree-strewn streets as they had for generations: by leaning on one another.

Flowers White said that it took days before anyone from the outside got to the neighborhood, and when help did come, it came in the form of religious charitable organizations and their neighbors rather than the state.

“We cook everything that’s in the house so it won’t spoil, and we set up a table,” Flowers said. “You pass by and you’re hungry, everybody gets something to eat.” It’s one of the ways he said the community depended on one another.

Flowers White said that it took days before anyone from the outside got to the neighborhood, and when help did come, it came in the form of religious charitable organizations and their neighbors rather than the state.

“We cook everything that’s in the house so it won’t spoil, and we set up a table,” Flowers said. “You pass by and you’re hungry, everybody gets something to eat.” It’s one of the ways he said the community depended on one another.

Pittman said that at least one of his friends would always be at his house helping with the demolition once he decided to stop waiting for funding. Much of the rebuilding was done by his own -- and his friends' -- hands. “Someone would always be there to help me and do what I need to do,” Pittman said.

Part of the problem facing hurricane-damaged homeowners was the bureaucracy that comes with federal, state and emergency funding programs.

FEMA and its local counterpart, the Mississippi Emergency Management Agency (MEMA), handled some of the temporary assistance for those with severe damage.

The Mississippi Development Authority (MDA), which is funded by the Department of Housing and Urban Development, handled longer-term home improvement grants. Funds provided by MDA were intended to help finance reconstruction to where it was before the storm and, with few exceptions, did not improve upon those designs to prevent damage in future storms.

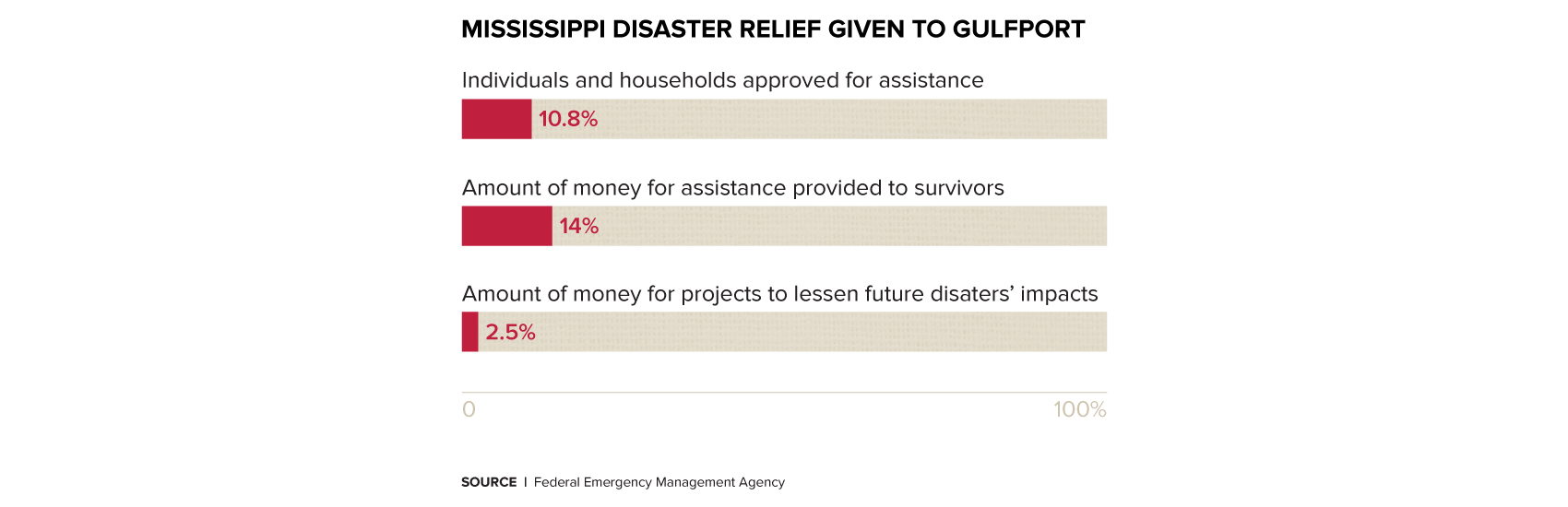

A FEMA spokesman confirmed to ABC News that $182 million was distributed throughout Gulfport (population: 71,022 in 2013) in housing and disaster-related expense payments, though records don’t show how much of that was earmarked for Turkey Creek.

FEMA awarded funds to more than half – 274,761—of the more than 500,000 statewide applications for individual assistance that it received by December 2005, MEMA spokesman Brett Carr told ABC News.

Part of the problem facing hurricane-damaged homeowners was the bureaucracy that comes with federal, state and emergency funding programs.

FEMA and its local counterpart, the Mississippi Emergency Management Agency (MEMA), handled some of the temporary assistance for those with severe damage.

The Mississippi Development Authority (MDA), which is funded by the Department of Housing and Urban Development, handled longer-term home improvement grants. Funds provided by MDA were intended to help finance reconstruction to where it was before the storm and, with few exceptions, did not improve upon those designs to prevent damage in future storms.

A FEMA spokesman confirmed to ABC News that $182 million was distributed throughout Gulfport (population: 71,022 in 2013) in housing and disaster-related expense payments, though records don’t show how much of that was earmarked for Turkey Creek.

FEMA awarded funds to more than half – 274,761—of the more than 500,000 statewide applications for individual assistance that it received by December 2005, MEMA spokesman Brett Carr told ABC News.

Pittman attempted to apply for funds through the second phase of MDA’s Homeowner Assistance Program. But in late October 2007, he received a letter from the MDA, which he shared with ABC News, saying that the household income they earned -- between his salary from working at the DuPont chemical plant and that of his wife working in the local school system – was in excess of $100,000 in 2006, which the letter stated was too high to receive federal funds.

“No one ever said that during the entire pitch on television and radio that applying for disaster help and all that that there was a ceiling cap on income and what not,” Pittman said.

MDA spokesman Jeff Rent told ABC News that eligibility requirements for the Homeowner Assistance Program were discussed in their outreach efforts, which included public meetings and face-to-face meetings with counselors at intake centers. Everyone was encouraged to apply, he said.

The MDA’s latest report on its work in the wake of the storm notes that Phase II eligibility was set to only include applicants who had an “income of 120 percent area median income or below.” The median income in the area surrounding Turkey Creek is not available for 2006, but the U.S. Census Bureau 2013 American Community Survey 5-year estimates place the median income at $20,527, putting Pittman out of the eligible range.

Through all stages of the Homeowner Assistance Program, HUD reports that it provided grants to more than 27,000 homeowners across the state.

Reilly Morse, the president and CEO of the Mississippi Center for Justice, a public interest law firm, worked with Turkey Creek residents to try and receive funding through a third source: Historic Preservation Grants provided by the Mississippi Department of Archives and History.

“No one ever said that during the entire pitch on television and radio that applying for disaster help and all that that there was a ceiling cap on income and what not,” Pittman said.

MDA spokesman Jeff Rent told ABC News that eligibility requirements for the Homeowner Assistance Program were discussed in their outreach efforts, which included public meetings and face-to-face meetings with counselors at intake centers. Everyone was encouraged to apply, he said.

The MDA’s latest report on its work in the wake of the storm notes that Phase II eligibility was set to only include applicants who had an “income of 120 percent area median income or below.” The median income in the area surrounding Turkey Creek is not available for 2006, but the U.S. Census Bureau 2013 American Community Survey 5-year estimates place the median income at $20,527, putting Pittman out of the eligible range.

Through all stages of the Homeowner Assistance Program, HUD reports that it provided grants to more than 27,000 homeowners across the state.

Reilly Morse, the president and CEO of the Mississippi Center for Justice, a public interest law firm, worked with Turkey Creek residents to try and receive funding through a third source: Historic Preservation Grants provided by the Mississippi Department of Archives and History.

Ken P'Pool, the deputy state historic preservation officer at the agency, told ABC News that nine properties in Turkey Creek were awarded a total of $680,000 largely between 2006 and 2007 from federal funds administered through the agency.

“There was almost panic among the residents there after Katrina that FEMA and or the local governments would just come in and bulldoze houses to clear the area out because there was widespread damage done by flooding during Katrina,” P’Pool told ABC News.

He said that concern prompted his agency to speed up the application they had been working on to include the neighborhood on the Register of National Historic Places. P’Pool said that status was then granted in 2006.

Morse was critical of FEMA for its placement of its Disaster Resource Centers, where residents could go to find out more about how to apply for funds. He claims they were placed in predominantly white neighborhoods of Gulfport when really many others were the ones that needed help most desperately.

“There was almost panic among the residents there after Katrina that FEMA and or the local governments would just come in and bulldoze houses to clear the area out because there was widespread damage done by flooding during Katrina,” P’Pool told ABC News.

He said that concern prompted his agency to speed up the application they had been working on to include the neighborhood on the Register of National Historic Places. P’Pool said that status was then granted in 2006.

Morse was critical of FEMA for its placement of its Disaster Resource Centers, where residents could go to find out more about how to apply for funds. He claims they were placed in predominantly white neighborhoods of Gulfport when really many others were the ones that needed help most desperately.

“Part of that at least at the very beginning might be chalked up to the catastrophic nature of the loss and figuring out what to do,” Morse said, “but when it dragged on week after week and it became clearer that they weren’t going to do anything, it became harder to excuse.”

“I don’t think it was as important to them. These folks weren’t as important to them,” Morse said of FEMA.

Brett Carr, the MEMA spokesman, told ABC News that location decisions were “absolutely not” made based on the demographic makeup of the areas, noting that there were concerns over site safety, space, electricity and an accessible location “that’s going to serve the most people.”

“I don’t think it was as important to them. These folks weren’t as important to them,” Morse said of FEMA.

Brett Carr, the MEMA spokesman, told ABC News that location decisions were “absolutely not” made based on the demographic makeup of the areas, noting that there were concerns over site safety, space, electricity and an accessible location “that’s going to serve the most people.”

The community was still recovering when Rev. Lindsey Robinson arrived in Turkey Creek in 2007, to take over as the leader of the neighborhood’s Mt. Pleasant United Methodist Church.

“A lot of my work at that point was dealing with the healing aspect of Katrina,” he said days before the church’s 135th anniversary earlier this month. “Persons were still grieving the loss of property, family memories that they had. They were still grieving.”

He said congregants told him they felt their survival was a miracle brought on by prayer. They said that, when they were in the water, fearing for their lives, “they prayed to the Lord the water stopped rising.”

“A lot of my work at that point was dealing with the healing aspect of Katrina,” he said days before the church’s 135th anniversary earlier this month. “Persons were still grieving the loss of property, family memories that they had. They were still grieving.”

He said congregants told him they felt their survival was a miracle brought on by prayer. They said that, when they were in the water, fearing for their lives, “they prayed to the Lord the water stopped rising.”

The church itself had little damage from the storm. It served as a refuge for those who were rescued when Katrina hit, and it ended up serving as a makeshift homeless shelter for those with nowhere else to go.

And every Saturday for a number of months following the storm, it also served as a Seventh Day Adventist Church when the house of worship for a nearby Hispanic community was severely damaged.

Robinson said that it was “three years, four years, five years” after the storm that the intention of the church could shift its attention from helping congregants stabilize their personal lives to the ministry of their religious community.

“With Katrina, nothing is never ‘back to normal.’ It’s a new normal,” he said.

And every Saturday for a number of months following the storm, it also served as a Seventh Day Adventist Church when the house of worship for a nearby Hispanic community was severely damaged.

Robinson said that it was “three years, four years, five years” after the storm that the intention of the church could shift its attention from helping congregants stabilize their personal lives to the ministry of their religious community.

“With Katrina, nothing is never ‘back to normal.’ It’s a new normal,” he said.

Back on the lawn, Flowers White watches the school buses lurch down Rippy Road – depositing their grandkids at various houses on the street.

The men tend to be more reflective than bitter, nodding in solidarity whenever a gripe comes up about the lack of assistance, but moving on moments later. They made it through that storm by banding together. They say they would do the same thing if another hit.

White sits up in his chair and looks out at the neighborhood where generations of his family grew up.

“After the storm, we didn’t have electricity for 11 days,” he said, “but we would sit outside in the evening time, at dark, and look and sit around and talk like people used to do. And you could look like through the woods and you could see the fireflies.

“I thought they were gone but they still here, it just wasn’t dark enough to see them.”

Special thanks to the Turkey Creek community, Bridge the Gulf Project, and Come Hell or High Water: The Battle for Turkey Creek.

Additional Credits

Executive Producer DAN SILVER

Managing Editor XANA O'NEILL

Supervising Producer RONNIE POLIDORO

Creative Design Director LORI NEUHARDT

Senior Developer GREG ATRIA

Interactive Designer JAN DIEHM

Video Editor ARTHUR NIEMYNSKI

Additional Producers OLIVIA SMITH, EVAN SIMON

The men tend to be more reflective than bitter, nodding in solidarity whenever a gripe comes up about the lack of assistance, but moving on moments later. They made it through that storm by banding together. They say they would do the same thing if another hit.

White sits up in his chair and looks out at the neighborhood where generations of his family grew up.

“After the storm, we didn’t have electricity for 11 days,” he said, “but we would sit outside in the evening time, at dark, and look and sit around and talk like people used to do. And you could look like through the woods and you could see the fireflies.

“I thought they were gone but they still here, it just wasn’t dark enough to see them.”

Special thanks to the Turkey Creek community, Bridge the Gulf Project, and Come Hell or High Water: The Battle for Turkey Creek.

Additional Credits

Executive Producer DAN SILVER

Managing Editor XANA O'NEILL

Supervising Producer RONNIE POLIDORO

Creative Design Director LORI NEUHARDT

Senior Developer GREG ATRIA

Interactive Designer JAN DIEHM

Video Editor ARTHUR NIEMYNSKI

Additional Producers OLIVIA SMITH, EVAN SIMON