The small, frail body sat on a miniature wooden tablet. Its bloodshot eyes reflecting its haunted past.

“The most shocking thing I think we have … is I think the tiger fetus,” Supervisory Wildlife Repository Specialist Coleen Schaefer told ABC News.

The fetus doesn’t look quite real. Its face bends down towards its tiny paws.

“When I see items like the tiger fetus you can become despondent,” Schaefer said.

Schaefer heads the National Eagle and Wildlife Property Repository northeast of Denver in Commerce City, Colorado. The 16,000-square-foot warehouse consists of approximately 1.5 million seized and confiscated illegal wildlife products.

“That’s just a thimbleful of what comes into the country every single year,” Schaefer said, referencing the amount of trafficked wildlife items in the U.S.

“The most shocking thing I think we have … is I think the tiger fetus,” Supervisory Wildlife Repository Specialist Coleen Schaefer told ABC News.

The fetus doesn’t look quite real. Its face bends down towards its tiny paws.

“When I see items like the tiger fetus you can become despondent,” Schaefer said.

Schaefer heads the National Eagle and Wildlife Property Repository northeast of Denver in Commerce City, Colorado. The 16,000-square-foot warehouse consists of approximately 1.5 million seized and confiscated illegal wildlife products.

“That’s just a thimbleful of what comes into the country every single year,” Schaefer said, referencing the amount of trafficked wildlife items in the U.S.

This is the only repository of its kind in the country. Aisles of animal parts and pieces fill the enormous space. Tiger heads line shelves, frozen in angry growls. Snakes float in liquids in jars. A rhino, cut up into many pieces, sits in the back. Officials estimate about 200 items come into the warehouse on a weekly basis.

Schaefer, 46, has been working at the repository for about a year.

“I don’t think the average American knows that the National Wildlife Property Repository exists,” she said.

The repository is stationed on the Rocky Mountain Arsenal National Wildlife refuge, which spans 15,000 acres.

Before it was a refuge, the U.S. Army used the land to build chemical weapons following the attack on Pearl Harbor. Later it was used by Shell Chemical Co. to produce agricultural chemicals.

Now the refuge is home to bison, prairie dogs, a number of birds and various animals that roam the land freely. And it houses the repository.

Schaefer, 46, has been working at the repository for about a year.

“I don’t think the average American knows that the National Wildlife Property Repository exists,” she said.

The repository is stationed on the Rocky Mountain Arsenal National Wildlife refuge, which spans 15,000 acres.

Before it was a refuge, the U.S. Army used the land to build chemical weapons following the attack on Pearl Harbor. Later it was used by Shell Chemical Co. to produce agricultural chemicals.

Now the refuge is home to bison, prairie dogs, a number of birds and various animals that roam the land freely. And it houses the repository.

While Americans may be familiar with isolated wildlife hunting incidents like Cecil the lion, Schaefer explained that commercialized, illegal trafficking is a larger issue at the moment because it’s increasing.

“Wildlife trafficking as I mentioned has changed from a crime of opportunity to a well-structured organized crime operation. It is a multi-billion dollar operation where it’s funding insurgencies,” Schaefer said. “It’s third to trafficking humans and drugs and firearms,” she added.

There is a low-risk aspect to wildlife trade, because other countries don’t have infrastructure or law enforcement to enforce against it, Schaefer said. That is why the Obama administration has come out with a national strategy and implementation plan against wildlife trafficking, with one objective being to strengthen global enforcement.

With the black market trade, it’s difficult to determine how much is being brought into the country because it’s illegal, so unless you catch every single illegal shipment you have no idea, Schaefer said.

“Wildlife trafficking as I mentioned has changed from a crime of opportunity to a well-structured organized crime operation. It is a multi-billion dollar operation where it’s funding insurgencies,” Schaefer said. “It’s third to trafficking humans and drugs and firearms,” she added.

There is a low-risk aspect to wildlife trade, because other countries don’t have infrastructure or law enforcement to enforce against it, Schaefer said. That is why the Obama administration has come out with a national strategy and implementation plan against wildlife trafficking, with one objective being to strengthen global enforcement.

With the black market trade, it’s difficult to determine how much is being brought into the country because it’s illegal, so unless you catch every single illegal shipment you have no idea, Schaefer said.

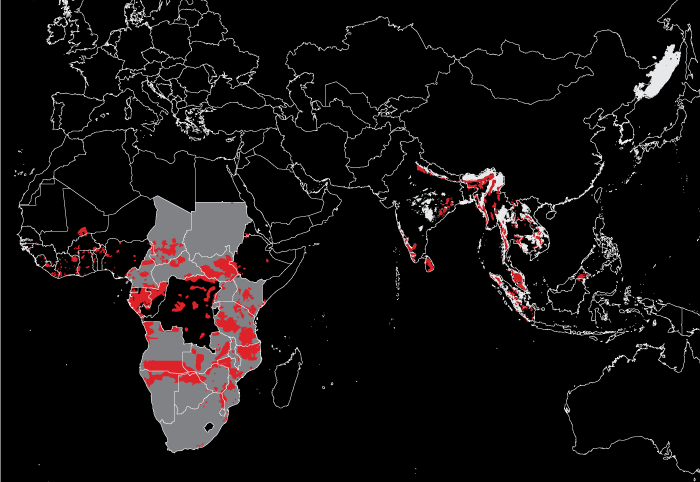

Habitats of the Big Three: Elephants, Rhinoceroses, Tigers

| ELEPHANTS | RHINOCEROSES | TIGERS |

|---|

| SPECIES | POPULATION | STATUS |

|---|---|---|

| African Elephant | 470,000 | Vulnerable |

| Asian Elephant | 40,000–50,000 | Endangered |

| Black Rhino | >5,000 | Critically endangered |

| Great One-Horned Rhino | >3,000 | Vulnerable |

| Javan Rhino | 60 | Critically endangered |

| Sumatran Rhino | <100 | Critically endangered |

| White Rhino | >20,000 | Near threatened |

| Tiger | Around 3,200 | Endangered |

SOURCES: International Union for Conservation of Nature and Natural Resources' Red List, World Wildlife Fund

“Legal wildlife value is a multi-billion dollar industry so you can extrapolate that value to the black market,” Schaefer said. “It has been estimated to be about $19 or $20 billion worth of illegal items that are coming into the country [a year].”

An item is deemed illegal if the importer is lacking the proper permits, including endangered species permits. CITES, or the Convention on International Trade in Endangered Species of Wild Fauna and Flora, is a treaty that was established to protect species from becoming extinct due to trade.

“Whenever there’s a commercial value in wildlife there will be some who want to exploit that value. If left unchecked, that animal will be exploited sometimes all the way down to extinction,” said U.S. Fish and Wildlife Special Agent Steve Oberholtzer.

Wildlife officials say agents like Oberholtzer are the first line of defense for products imported into and exported out of the country. If an item is in violation, it is seized and a case is opened. Once the case is closed it is sent to the repository.

“There’s lots of different techniques to document the illegal activity going on,” Oberholtzer said. “Sometimes those techniques are undercover operations, sometimes they’re more overt operations where we serve search warrants or subpoenas or testify in front of the grand jury -- lots of different ways to uncover the truth about the illegal taking of wildlife.”

Items in the warehouse may also have been forfeited or abandoned. Once an item ends up there a few things can happen to it. It will either stay for educational purposes or it will be destroyed or donated to a school or museum.

A major concern facing wildlife trafficking now includes the rapid loss of tigers, elephants and rhinoceroses.

The reason people desire rhino horns, once used more traditionally in different cultures as cures to treat various ailments, has changed to become more of a status symbol. The horn is used in certain countries now as a hangover cure.

“So they’re increasing the poaching to provide this rhinoceros horn and that’s more valuable than cocaine or platinum,” Schaefer said. "It’s estimated at around $60,000 per kilo," she added.

Schaefer said at the current rate of poaching, we could lose elephants as a species in the wild within the next decade.

“Imagine your children now who would no longer be able to see or draw or talk about an elephant. It would become more like a woolly mammoth. These are things that are very real and possible.”

Schaefer said it’s a simple issue of supply and demand.

“Everybody can help be a solution to the problem by reducing demand for such items … If nobody were buying it, the demand would decrease and so would the supply,” she said.

Published on October 30, 2015

Additional Credits

Video Editor BENJAMIN SCHELLPFEFFER

Executive Producer DAN SILVER

Managing Editor XANA O'NEILL

Supervising Producer RONNIE POLIDORO

Creative Design Director LORI NEUHARDT

Interactive Designer JAN DIEHM

Senior Developer GREG ATRIA

Additional Producer CLAYTON SANDELL

A major concern facing wildlife trafficking now includes the rapid loss of tigers, elephants and rhinoceroses.

The reason people desire rhino horns, once used more traditionally in different cultures as cures to treat various ailments, has changed to become more of a status symbol. The horn is used in certain countries now as a hangover cure.

“So they’re increasing the poaching to provide this rhinoceros horn and that’s more valuable than cocaine or platinum,” Schaefer said. "It’s estimated at around $60,000 per kilo," she added.

Schaefer said at the current rate of poaching, we could lose elephants as a species in the wild within the next decade.

“Imagine your children now who would no longer be able to see or draw or talk about an elephant. It would become more like a woolly mammoth. These are things that are very real and possible.”

Schaefer said it’s a simple issue of supply and demand.

“Everybody can help be a solution to the problem by reducing demand for such items … If nobody were buying it, the demand would decrease and so would the supply,” she said.

Published on October 30, 2015

Additional Credits

Video Editor BENJAMIN SCHELLPFEFFER

Executive Producer DAN SILVER

Managing Editor XANA O'NEILL

Supervising Producer RONNIE POLIDORO

Creative Design Director LORI NEUHARDT

Interactive Designer JAN DIEHM

Senior Developer GREG ATRIA

Additional Producer CLAYTON SANDELL