Former skater sues coach, federation over alleged sexual abuse and coverup

It is the latest chapter in a two-decade-long fight for accountability.

Craig Maurizi, a onetime Olympic hopeful turned Olympic coach, has filed a $10 million lawsuit against famed figure skating coach Richard Callaghan and a trio of skating institutions, including U.S. Figure Skating, the sport’s national governing body.

In his complaint, filed in the U.S. District Court for the Western District of New York, Maurizi, 57, alleges that Callaghan “used his position of trust and authority to psychologically groom Craig for what turned into nearly a decade of sexual abuse” in the 1970s and 1980s, and the sport’s leaders “conspired to circumvent their own internal procedures to sweep Craig’s complaints under the rug.”

The lawsuit is the latest chapter in a fight for accountability that has already spanned more than two decades. Maurizi’s allegations against Callaghan have been the subject of confidential investigations, media reports and legal proceedings, and they have been repeatedly corroborated and even, most recently, validated by the independent watchdog organization responsible for eradicating sexual misconduct in the Olympic Movement.

And it is the second lawsuit in which a former student of Callaghan alleges that U.S. Figure Skating was negligent in its duty to protect its athletes from an allegedly predatory coach. The two cases are closely linked.

Adam Schmidt, 35, another former skater turned coach, has alleged that he suffered “numerous sexual assaults” by Callaghan while training under him as a teenager in Michigan from about 1999 to 2001, after U.S. Figure Skating dismissed Maurizi’s allegations against Callaghan. That decision, Schmidt’s complaint said, allowed Callaghan’s alleged abuse of Schmidt to “continue unabated,” resulting in what the complaint describes as a litany of trauma-related psychological damages, including “anxiety, depression, fear, grief and stress.”

Yet Callaghan, 74, who has faced multiple allegations of sexual, physical and emotional misconduct from the elite skaters he coached, will be eligible to return to the ice in 2022, after his lifetime ban from the sport was controversially overturned by an arbitrator who said he believed Callaghan abused Maurizi but felt bound to apply what he called “absurd and draconian” rules of evidence in his decision.

“I’m still haunted when I allow myself to think about how Callaghan manipulated my mind and body to make me dependent on him, how he abused me under the guise of being a father figure when I was most vulnerable,” Maurizi told ABC News in a statement. “By the time I’d come to terms with Callaghan's abuse 20 years later, it was too late for the criminal justice system to help me. I took my grievance to USFS but they threw it out without even talking to me. I took my grievance to the PSA and they too swept it under the rug. In more recent years, SafeSport investigated and fully credited all my allegations against Callaghan, but the end result was that Callaghan got off with a slap on the wrist.”

Callaghan, who was actively coaching in Florida until 2018, when he was suspended by U.S. Figure Skating pending an investigation, has repeatedly denied any misconduct. He has since filed for bankruptcy.

Attorneys for Callaghan did not respond to multiple requests for comment from ABC News.

Maurizi is suing under the Child Victims Act, signed by New York Governor Andrew Cuomo last year, which created a one-year window from August 14, 2019 to August 14, 2020, in which victims of childhood sexual abuse could bring legal action against alleged abusers and enablers regardless of the statute of limitations. Hundreds of cases have since been filed against several major institutions, most notably the Catholic Church and the Boy Scouts of America.

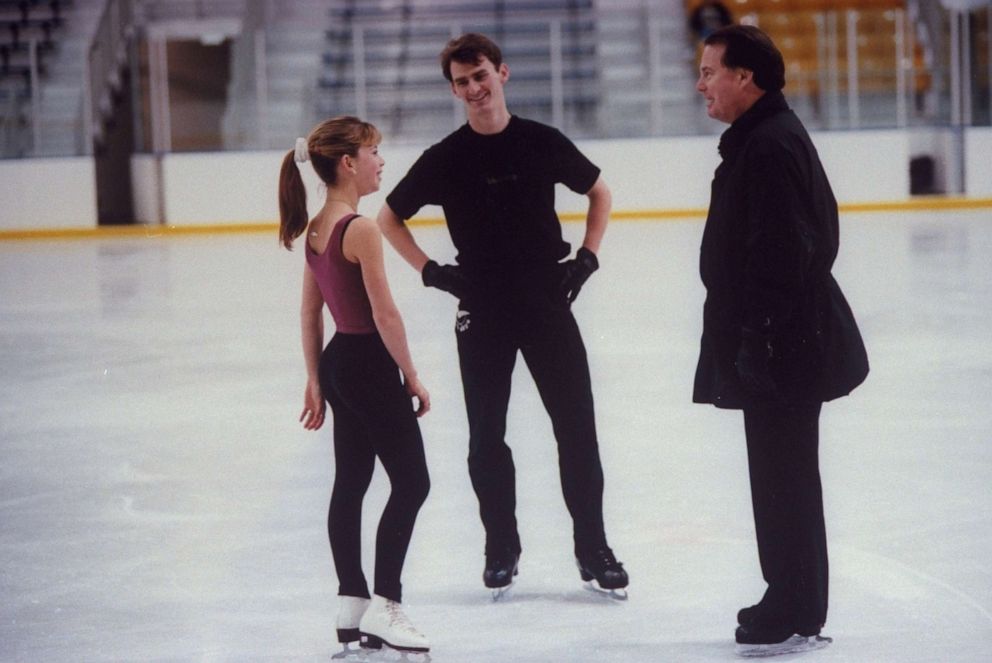

Maurizi’s attorney, Ilene Jaroslaw, a partner at the New York-based firm Phillips Nizer, said Callaghan’s success on the ice – he famously led Tara Lipinski to an Olympic gold medal at the 1998 Winter Games in Nagano, Japan – shielded him from consequences.

“For decades, the U.S. figure skating establishment has willfully turned a blind eye to sexual exploitation of young ice skaters by abusive coaches,” Jaroslaw told ABC News. “As long as Richard Callaghan brought home medals and accolades, U.S. Figure Skating, the Professional Skaters Association, and the Buffalo Skating Club were there to cover up for him. Because of Craig Maurizi’s courage and persistence, and thanks to New York State’s Child Victims Act, Callaghan and his corporate enablers will finally be held to account. Craig may not have been the first nor the last of Callaghan’s victims, but he will fight hard to make sure that Callaghan never has access to young skaters again.”

U.S. Figure Skating has acknowledged that “Maurizi’s case prompted U.S. Figure Skating to examine its rules and procedures in the area of Athlete Safety,” leading them to introduce mandatory reporting requirements, but insisted that the federation “has acted promptly on every incident reported to it of suspected sexual abuse or misconduct since the new policy was enacted in May 2000” and denied any allegations of a coverup.

A spokesperson for U.S. Figure Skating declined to comment on the lawsuit.

The lawsuit repeats allegations that Maurizi has previously told ABC News. Over the course of several years, Mauruzi said, starting when he was a teenage skater and continuing until he was a young coach, Callaghan groomed and sexually abused him between 1977 and 1986.

“[Callaghan] exploited Craig’s vulnerability due to his parents’ divorce, manipulating Craig to make him increasingly isolated and dependent on Callaghan,” the complaint alleges. “Callaghan tempted Craig with pornography and alcohol, and gradually escalated his demands from sexual banter, to forcibly touching Craig’s genitals, to mutual masturbation, and ultimately to oral and anal sex.”

But when Maurizi reported the alleged abuse, in a grievance filed with the federation in 1999 that included statements from several other people who had either suffered or witnessed sexual misconduct by Callaghan, he was rebuffed. In what Maurizi has described as “a deliberate coverup,” the federation dismissed the grievance without full consideration because skating bylaws stipulated that alleged misconduct must be reported within 60 days. A similar review by the Professional Skaters Association, a trade association for coaches, was also dismissed.

Callaghan — one of the world’s top coaches at the time, whose list of students then included some of the sport’s biggest names — was allowed to continue coaching.

“[The U.S. Figure Skating Association] and [the Professional Skaters Association] were more concerned with covering up their own knowledge of and complicity in Callaghan’s abuse,” the complaint alleges, “than holding Callaghan accountable for his gross abuse of his power as a coach and protecting young figure skaters from abuse.”

In response to questions from ABC News, PSA executive director Jimmie Santee issued a brief statement.

“PSA has not received official notification of the lawsuit and we have no further information. Craig Maurizi is a current member in good standing of our organization and Mr. Callaghan remains suspended from PSA since the 2018 determination from the U.S. Center for SafeSport,” Santee said. “PSA is committed to the safety of athletes and reports all claims of abuse to the U.S. Center for SafeSport and local authorities. PSA provides both education and instruction to its members directing them to report any suspicious activity to SafeSport and the local authorities.”

But Maurizi’s complaint further alleges that Callaghan’s sexual predation amounted to “an open secret throughout the United States figure skating community” and that his sexual abuse of Maurizi in particular was “widely known” among the officials of the sport’s institutions.

The lawsuit cites internal complaints and discussions about Callaghan’s alleged misconduct circulating among board members at the Buffalo Skating Club, where Maurizi began taking lessons from Callaghan in the 1970s, and among U.S. Figure Skating judges “as far back as 1974.”

The Buffalo Skating Club eventually fired Callaghan, the complaint alleges, but “much like the hierarchy of the Catholic Church, BSC did nothing to stop Callaghan, but merely passed him along to the next skating club looking for a coach who could produce winners.” U.S. Figure Skating, meanwhile, the complaint alleges, took “no action” to revoke his membership and thereby restrict his access to young skaters.

Officials from the Buffalo Skating Club declined to comment and referred inquiries to U.S. Figure Skating.

U.S. Figure Skating has said that it has no record of any complaints about Callaghan’s alleged misconduct prior to Maurizi’s grievance.

“No allegations against Mr. Callaghan were reported prior to 1999,” a U.S. Figure Skating spokesperson told ABC News. “U.S. Figure Skating records reflect that Mr. Maurizi remains the only person to have reported allegations against Richard Callaghan to U.S. Figure Skating.”

But ABC News found a reference to what appears to be a previous investigation of Callaghan’s conduct by U.S. Figure Skating. In an article published by the Chicago Tribune in 1999, Philip Hersh reported that former USFSA President Claire Ferguson “investigated six years ago rumors of misconduct by Callaghan and found nothing to substantiate them.” ABC News has been unable to reach Ferguson for comment.

U.S. Figure Skating denied having any records of such an inquiry.

“U.S. Figure Skating has no record of any ‘investigation into rumors’ about Mr. Callaghan prior to 1999,” a U.S. Figure Skating spokesperson told ABC News. “News reports in 1999 clearly stated Mr. Maurizi’s report against Callaghan was the first and only report received by U.S. Figure Skating against Callaghan.”

Maurizi alleges, in the complaint, that U.S. Figure Skating short-circuited its grievance process in order to shield Callaghan from scrutiny. ABC News found, in its review of the documents related to Maurizi’s grievance submitted to the federation, that Steven Hazen, the former skating official who was charged with handling Maurizi’s initial complaint against Callaghan, accused his onetime colleagues of trying to suppress the review.

In letters obtained by ABC News, Hazen cited a “blatant attempt to interfere with the grievance process” in an “effort to intimidate me into abandoning my responsibilities” before he was ultimately removed from his position entirely.

“It wasn’t clear to me where the resistance lay,” Hazen told ABC News, “but it was clear to me that there were people at USFSA who did not want that matter to go forward.”

Ultimately, it was then-U.S. Figure Skating president Jimmy Disbrow, who ran the sport from 1998 to 2000 before he died in 2002, who made the final determination on the matter. He ruled that Maurizi's claims were being dismissed "for a variety of reasons, both legal and equitable, pertaining principally to delay and limitation of actions.”

Shortly after, in 1999, Disbrow told the New York Times that the claim’s merits were not judged. “The whole process is that you try to do things that are timely,” Disbrow told the Times. “It's not an issue of guilt on anybody's part. I'm not saying 'right or wrong' on anybody's part. The fact is, this thing is 14 years old.”

Maurizi has long maintained that the evidence of Callaghan’s misconduct was “overwhelming,” and in the only available record of an official investigation into his allegations against Callaghan, investigators appeared to agree with him.

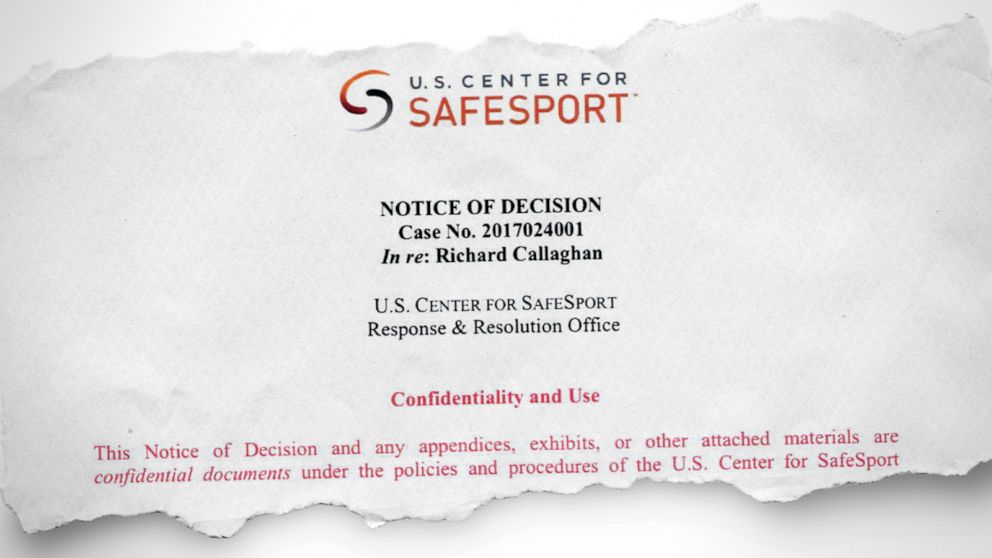

In 2018, Maurizi submitted a complaint to the newly formed U.S. Center for SafeSport, which was authorized by Congress to investigate cases on behalf of the national governing bodies under the umbrella of the U.S. Olympic and Paralympic Committee. A tranche of confidential documents obtained by ABC News and ESPN reveal that SafeSport’s investigators found that Callaghan had engaged in various forms of misconduct with both male and female skaters.

In a 53-page report summarizing about 200 pages of evidence gathered across interviews with 17 different people, SafeSport’s investigators outlined a litany of findings against the coach.

“This investigation found by a preponderance of the evidence that, over the course of two decades, [Callaghan] engaged in grooming behavior, non-contact behavior of a sexual nature, inappropriate physical contact, and sexual contact and intercourse, physical and emotional misconduct, and a pattern of exploitative and abusive conduct with young athletes he coached,” the investigators wrote.

SafeSport initially banned Callaghan from the sport for life in August, but an arbitrator overturned that decision in December and reduced the penalties to a three-year suspension, 15-year probation and 100 hours of community service, primarily for physical and emotional misconduct against female skaters, dismissing Maurizi’s claims of sexual misconduct because of procedural rules regarding conduct that preceded SafeSport’s existence.

He applied a since-repealed law adopted in New York in 1980, which required “corroboration” for certain sexual offenses. Without a witness to, or other corroborating evidence of, the sexual abuse, in other words, he concluded his hands were tied.

“The undersigned sympathizes with Mr. Maurizi and acknowledges and agrees that his testimony confirms the sexual abuse occurred as described,” wrote the arbitrator. “However, SafeSport failed to produce corroborating evidence as required … The standard in effect at the time of the sexual acts required heightened evidence that is absurd, but that is the standard the undersigned must apply to this case. Accordingly, with regret, the undersigned finds that the conduct of Callaghan pertaining to Mr. Maurizi does not violate the [SafeSport Code for Olympic and Paralympic Movements].”

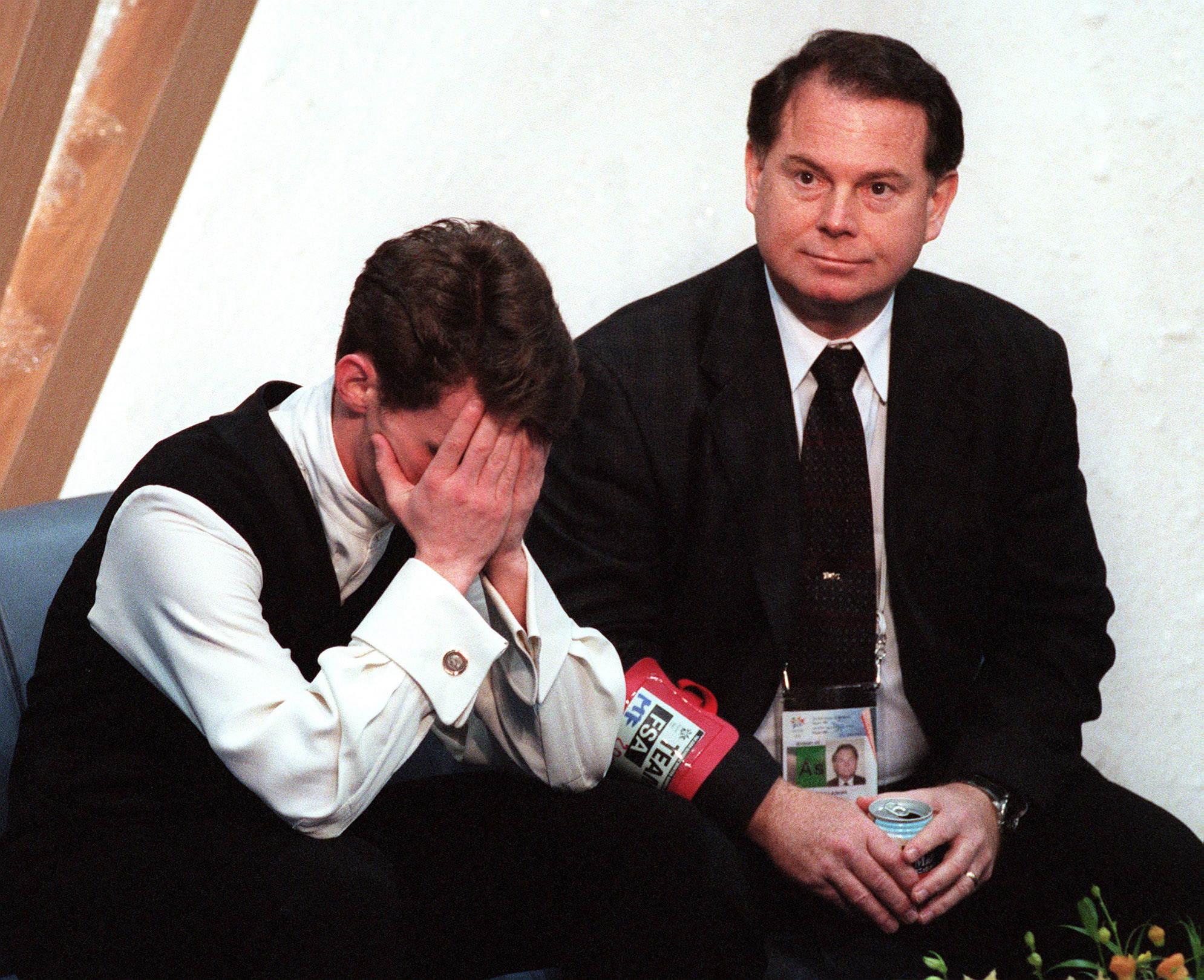

For Maurizi, the news of the reversal was devastating.

“I’m shocked and disappointed,” Maurizi told ABC News and ESPN at the time. “SafeSport was put in place to stop predators. But, in my case, they did just the opposite.”

With the lawsuit, Maurizi hopes to change the system that he feels failed him.

“The organizations that allowed Callaghan to flourish while they knew he was exploiting young figure skaters have a responsibility to acknowledge that their system is broken and that they wronged me and other athletes by placing a higher value on winning than on our well-being,” Maurizi said. “I hope this case puts an end to Callaghan’s coaching career once and for all, and that the organizations that enabled him acknowledge their failures and commit to protecting the athletes who train and compete under their auspices.”