John Edwards Case: Legal Team Seeking Dismissal

US Justice Dept.

From the moment the ink dried on the federal indictment of John Edwards, his lawyers have been waging an all-out assault on the government’s case against the disgraced former Democratic presidential candidate, who stands accused of six felonies in connection with an alleged cover-up of his extra-marital affair during the 2008 election campaign.

Standing outside the federal courthouse in Winston-Salem, N.C., last June, defense attorney Greg Craig pronounced: “This is an unprecedented prosecution. In the history of federal election campaign law, no one has ever been charged … with the claims that have been brought against Senator Edwards today.”

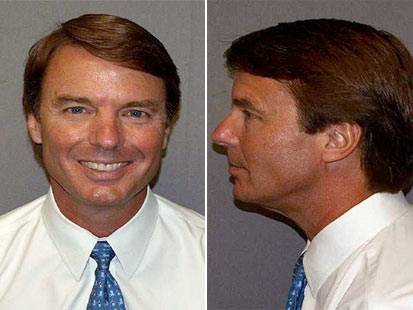

As Craig spoke out front, Edwards was being escorted around back into a small holding room, where the former golden boy of Democratic politics would experience the indignity of getting fingerprinted and photographed by U.S. Marshals. Ever the politician, Edwards managed a broad smile as his picture was snapped.

“He has broken no law,” Craig concluded on the courthouse steps, “and we will defend this case vigorously.” Moments later, Edwards entered not guilty pleas to all counts in the indictment. The fight was on.

This morning in Greensboro, N.C. Edwards’ legal team, now led by high-profile lawyer Abbe Lowell, will take those arguments and others before a federal judge, seeking dismissal of all the charges. They’re challenging virtually every aspect of the indictment, including what Lowell has referred to as the government’s “radical theory,” that third-party payments to a candidate’s mistress could be considered campaign-related expenditures.

The government has charged Edwards with knowingly conspiring to accept more than $900,000 in illegal contributions from two wealthy donors in an effort to conceal his affair and support his pregnant mistress, Rielle Hunter, while he was pursuing the Democratic nomination for president. Each of the six felony counts carries the potential for five years imprisonment.

The prosecutors contend that those payments violate federal election laws which regulate contributions intended to influence the outcome of an election. Edwards’ lawyers have countered that the payments were gifts to assist Hunter and Young, and therefore not subject to contribution limits.

The stakes are high at today’s hearing for both sides. If Edwards loses, he faces the prospect of a costly and embarrassing trial — at the end of which he could lose his freedom. For the government, a dismissal of the charges would result in a fantastic amount of egg on its face — after spending more than two years and millions of dollars investigating a man who long ago lost any chance of a political future.

If the case were to proceed to trial, the prosecution’s key witness would be former Edwards’ aide Andrew Young, who once falsely claimed to be the father of Hunter’s child. Young later retracted the claim and wrote a book, The Politician, which outlined what he claimed was an elaborate and expensive cover-up, led by Edwards, to hide Hunter from the press and from Edwards’ cancer-stricken wife, Elizabeth, who died late last year.

Young has legal trouble of his own. He is due in court early next month to answer charges that he violated a protective order prohibiting him from sharing information gathered in civil suit Hunter filed against him last year. In that suit, Hunter alleges that Young took from Hunter a series of private photographs and an explicit videotape featuring her and Edwards in a sexual encounter.

Young has denied Hunter’s allegations and says he kept the items only to protect himself and to help corroborate the assertions he made in his book.

Earlier this year under subpoena from the federal government Young turned over evidence from that case — including transcripts of depositions from Edwards and Hunter — to the prosecutors pursuing the case. Hunter’s attorneys have asked a judge to hold Young and his attorneys in contempt, arguing that he was obligated by the protective order to inform them of the subpoena from the federal government.

Young denies that and says that the judge in the civil case was consulted before his lawyers turned over the evidence in their possession.