Large Dinosaurs Had Hundreds of Teeth to Spare

It seems like some of the largest dinosaurs in prehistoric times didn't need to make dental health a priority.

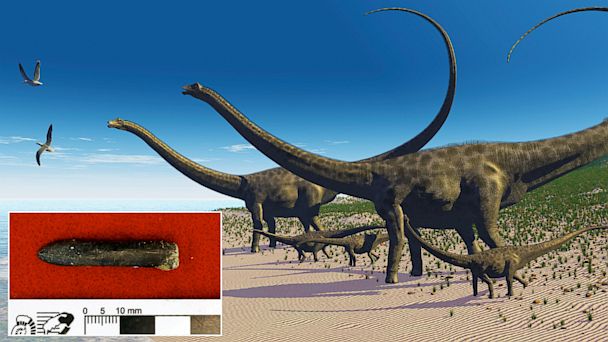

A new study published in the journal PLoS One examined the teeth of Camarasaurus and Diplodocus dinosaurs and found that they not only had multiple sets of backup teeth, but also constantly regenerated new ones.

John Whitlock, one of the main co-authors of the study and an assistant professor of science and mathematics at Mount Aloysius College in Pennsylvania, relied on the kindness of museum collection managers to do the study.

"Convincing them to let us cut up some of their fossils … it's not the easiest thing in the world," he told ABC News. "We were pretty lucky."

Michael D'Emic, the other main co-author and a paleontologist at Stony Brook University, said that getting to the teeth required an incredible amount of work.

"The fossil preparer spent about six months painstakingly extracting the teeth with this small jackhammer about the size of a pinhead," he said.

Beneath the dinosaurs' outermost layer of teeth were several more rows waiting on deck. Though the number of teeth varies from species to species, D'Emic said that the skulls contained 200 teeth or more at any given time.

To measure how old the teeth were, the two scientists cut the teeth apart, sanded and polished them to get even thinner slices, and photographed them using specialized cameras. The pictures revealed layers, similar to how tree trunks have rings. The scientists counted the layers to determine the age of the teeth.

On average, Camarasaurus lost and replaced one tooth every two months, while Diplodocus did so every month, they concluded.

Even though the animals themselves were gigantic, their heads and teeth were relatively small. "If you took a number two pencil and broke it into thirds, that's about the size and shape of a Diplodocus tooth," said Whitlock.

Mark Norell, the curator-in-charge of fossil reptiles, amphibians and birds at the American Museum of Natural History, said that the high rate of teeth turnover had to do with the dinosaurs' constant eating.

"If you think about herbivores today, they're eating almost 24 hours a day," he said. "It's the same with these dinosaurs back then."

Given how quickly and often teeth were lost and regenerate, you might expect an abundance of single tooth fossils waiting to be discovered.

Norell didn't think so, though, or at least people won't be able to recognize the fossils as teeth.

"The teeth are worn down into tiny pieces when they fall out, so they're non functional," he said.