We often think of first responders as the emergency agencies who come to the aid of those in need. But in the Gulf Coast, after Hurricane Katrina, there was another heroic group of rescuers who took immediate action: The food community.

In the wake of the hurricane, as we discover in our ABC News special, "Katrina: 10 Years After the Storm," with Robin Roberts, airing on Sunday, Aug. 23 at 10 p.m. EST, chefs and restaurant owners teamed up to became a vital life force, sustaining those who were trying to rebuild their broken lives, and gently nurturing the Gulf Coast back from devastation.

CHEF JOHN BESH: SERVING COMFORT FOOD

When Katrina struck, John Besh was a rising celebrity chef and owner of the award-winning restaurant, August. He had no illusions about how the hurricane would affect his city.

“We knew this was that storm that we had talked about my entire life. It scared me,” he said.

What he couldn’t predict was how the flooding of his city, and the terrible toll Katrina took on his own home area of Slidell, Louisiana, would completely change his future and the purpose of his career.

Right after Katrina he says, “I realized that my days of serving fancy, highfalutin customers were over with. At least, you know, I thought, forever.”

Today he is the proud owner of 12 acclaimed restaurants, and known for his books, TV shows, and Ted Talk. For Besh, a former Marine, what mattered most was taking action to help.

“It really became about just serving people from the heart," he said. "And cooking for people that were hungry changed the way I'll think about food and serving people for the rest of my life.”

He created a series of soup kitchens, serving the most basic and beloved dish: red beans and rice, a meal dished up every Monday in many households in the Gulf Coast.

“I wanted to feed people something that would feed more than their bodies, but nutrition for the soul, you know,” Besh said.

As the city began to recover, many of the people who knew how to cook the most iconic New Orleans dishes -- gumbos and jambalaya, for example -- had evacuated and were not able to return. Besh said it became clear to him that the very food he and others loved, and depended upon, was incredibly vulnerable.

“It took Katrina and all that devastation for us to understand how fragile our culture is. It's as fragile as those wetlands that protect us from the next storm. It's as fragile as the levee system,” he said.

Which is why he has since developed a foundation that provides micro-loans to local farmers, and a scholarship program to help a population of undeserved men and women from New Orleans rise in the ranks of the New Orleans culinary world.

To this day, Besh keeps alive the lesson he learned from Katrina, saying, “I have to do something to protect this culture, to make sure that this culture's passed on to another generation."

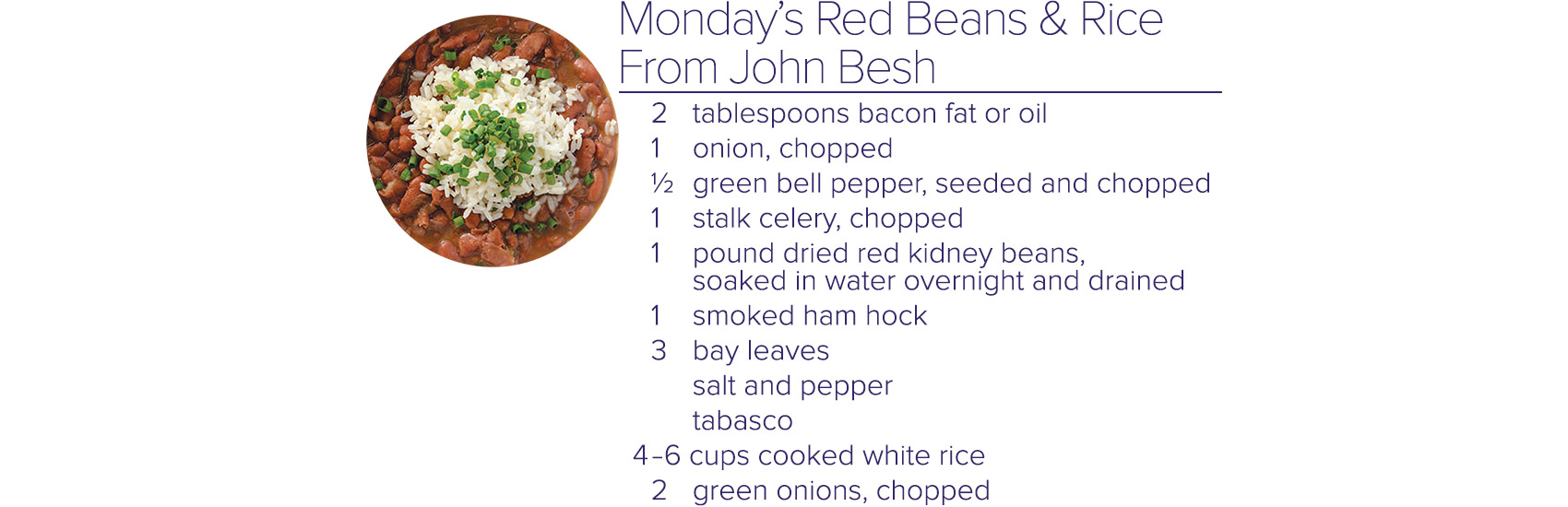

A note from John Besh: It’s a tradition in NOLA to eat red beans and rice on Monday. Here’s my Big Easy way to cook rice: Put a couple of tablespoons chicken fat, oil, or butter in a saucepan; add some chopped onion; sweat it down; then add a bay leaf and a pinch of salt. Soften the onions, add the rice, and stir to coat until the grains are shiny. Add stock or water: 2 parts liquid to 1 part rice. Stir, cover, and simmer for 20 minutes.

Serves 6

Heat the bacon fat in a large heavy-bottomed pot over medium-high heat and sweat the onions, bell peppers, and celery. Once the onions become translucent, add the beans, ham hock, bay leaves, and water to cover by 2 inches.

Raise the heat, bring the water to a boil, then lower the heat and cover the pot. Let the beans slowly simmer for 2 hours, stirring from time to time to make sure they do not stick and adding water to keep them covered by at least an inch. Continue cooking the beans until they become so tender they begin to fall apart and become creamy when stirred.

Remove the ham hock from the pot and take the meat off the bone. Roughly chop and return to the pot. Season with salt, pepper, and Tabasco. Serve the beans in bowls topped with white rice and green onions.

Recipe is from Chef John Besh's forthcoming cookbook Besh Big Easy: 101 Home Cooked New Orleans Recipes, out Sept. 29, but available for pre-order now on Amazon.com. Photo credit: Ditte Isager/EdgeReps

Serves 6-8

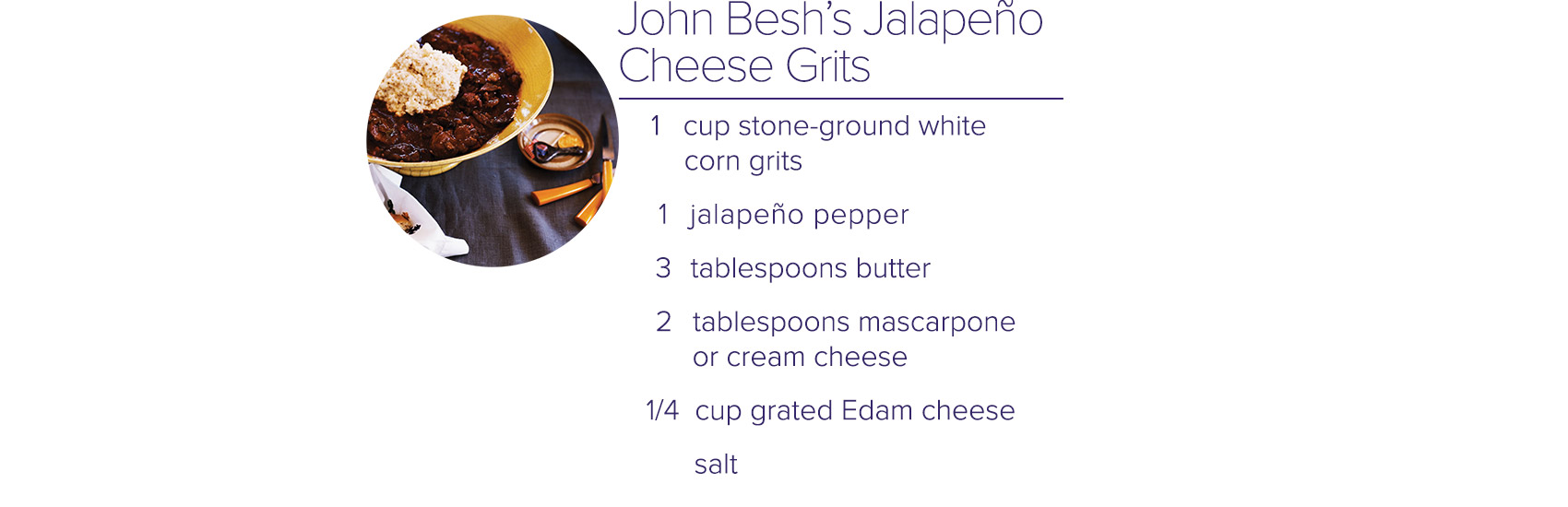

A note from John Besh: These cheesy grits are the perfect base for veal grillades or almost anything.

Heat 4 cups of water in a large heavy-bottomed pot over high heat until it comes to a boil. Slowly pour in the grits while whisking constantly. Reduce the heat to low, cover, and cook, stirring occasionally with a wooden spoon, for about 20 minutes.

While the grits are cooking, pan-roast the jalapeño pepper in a small skillet over high heat until the skin is brown and blistered. Cut the pepper in half lengthwise and remove the skin and the seeds from the pepper and discard. Mince the flesh and add it to the pot of grits.

Remove the pot from the heat and fold in the butter, mascarpone, and Edam cheese. Season with salt.

Recipe from “My New Orleans” by John Besh/Andrews McMeel Publishing. Photo credit: Ditte Isager/EdgeReps

A note from John Besh: These cheesy grits are the perfect base for veal grillades or almost anything.

Heat 4 cups of water in a large heavy-bottomed pot over high heat until it comes to a boil. Slowly pour in the grits while whisking constantly. Reduce the heat to low, cover, and cook, stirring occasionally with a wooden spoon, for about 20 minutes.

While the grits are cooking, pan-roast the jalapeño pepper in a small skillet over high heat until the skin is brown and blistered. Cut the pepper in half lengthwise and remove the skin and the seeds from the pepper and discard. Mince the flesh and add it to the pot of grits.

Remove the pot from the heat and fold in the butter, mascarpone, and Edam cheese. Season with salt.

Recipe from “My New Orleans” by John Besh/Andrews McMeel Publishing. Photo credit: Ditte Isager/EdgeReps

TOMMY CVITANOVICH OF DRAGO'S: GIVING BACK BIG TO THE BIG EASY

“There’s a reason why the windshield is way bigger than the rearview mirror," Tommy Cvitanovich said. "Sure we gotta look back and not forget, but we gotta look forward.”

The owner of Drago’s Seafood Restaurant, famous for its grilled oysters, says his post-Katrina motto has become a way of life.

But some might say he is being modest not to at least glance back at what he accomplished after the storm. Very quickly, Drago’s set up refrigerated trucks in their restaurant’s parking lot.

“We gave away over 75,000 meals in the eight weeks after storm,” Cvitanovich said. “Both in our Metairie location, and in Lakeview where the 17th street canal broke, in front of the church I went to as a little boy, a block from where the original restaurant was.”

When the city flooded, he and his staff knew their only focus was to help others. The restaurant, started in the 1969 by Cvitanovich’s immigrant Croatian parents, Drago and Kalra, already had a long history of community service. In the crisis that followed Katrina, it was second nature to the family to do all that they could to feed those in need.

Though today he does not want to dwell on the hurricane, Cvitanovich does assess how far New Orleans has come since the storm.

“We are growing internally in our hearts," he said. "That’s where we’ve done the most growing. We really take pride in our city. There’s a reason we are the hospitality capital. It’s the people.”

“There’s a reason why the windshield is way bigger than the rearview mirror," Tommy Cvitanovich said. "Sure we gotta look back and not forget, but we gotta look forward.”

The owner of Drago’s Seafood Restaurant, famous for its grilled oysters, says his post-Katrina motto has become a way of life.

But some might say he is being modest not to at least glance back at what he accomplished after the storm. Very quickly, Drago’s set up refrigerated trucks in their restaurant’s parking lot.

“We gave away over 75,000 meals in the eight weeks after storm,” Cvitanovich said. “Both in our Metairie location, and in Lakeview where the 17th street canal broke, in front of the church I went to as a little boy, a block from where the original restaurant was.”

When the city flooded, he and his staff knew their only focus was to help others. The restaurant, started in the 1969 by Cvitanovich’s immigrant Croatian parents, Drago and Kalra, already had a long history of community service. In the crisis that followed Katrina, it was second nature to the family to do all that they could to feed those in need.

Though today he does not want to dwell on the hurricane, Cvitanovich does assess how far New Orleans has come since the storm.

“We are growing internally in our hearts," he said. "That’s where we’ve done the most growing. We really take pride in our city. There’s a reason we are the hospitality capital. It’s the people.”

A note from the restaurant: Serves eight to 12 normal people, or two serious oyster fanatics.

1. Mix butter with the garlic, pepper, and Italian seasoning.

2. Heat a gas or charcoal grill and put oysters on the half shell right over the hottest part. Spoon the seasoned butter over the oysters enough so that some of it will overflow into the fire and flame up a bit.

3. The oysters are ready when they puff up and get curly on the sides. Sprinkle the grated Parmesan and Romano and the parsley on top. Serve on the shells immediately with hot French bread.

Recipe and photo courtesy of Drago's Seafood Restaurant

COMMANDER’S PALACE: 'WE KNOW WHAT IT MEANS'

It was the reopening of Commander’s Palace -- arguably one of the most famous restaurants in the South, long considered the jewel in the crown of iconic New Orleans food establishments -- that was a milestone in the city’s recovery, proving New Orleans and the Gulf Coast would not be beaten by Katrina.

“You know we didn’t know what was going to happen to the city of New Orleans, but we knew we were going to reopen no matter what,” says Lally Brennan who, along with her cousin Ti Martin, owns Commander’s.

As with other restaurants whose staff became the backbone of rebuilding, it was the Commander’s employees -- those who were able to return -- who pitched in to resurrect the ailing restaurant.

“People who had lost everything, their homes, everything, were there helping,” Brennan recalls.

Chief among them is Tory McPhail, the executive chef of Commander’s Palace. McPhail recalls pulling down moldy sheetrock until the interior walls of the stately rooms were stripped to their studs. “We all felt this was our house, and we would not see it fall apart on our watch,” he said.

The restaurant was not flooded out like some, but the damage from Katrina was disastrous for the elegant Victorian building. Wind, and flying debris, gauged holes in the roof and sides of the building, then rain poured inside. Very soon black mold grew throughout, and Commander’s Palace required an almost complete gutting. By day McPhail would help with the renovation. At night he would dream of what to cook when they came back.

To keep hope alive, the Brennan family hung a banner with a message to their patrons above the door that said “We Know What It Means,” paraphrasing the famous Louis Armstrong song, “Do You Know What it Means to Miss New Orleans?”

It took more than a year for Commander’s Palace to reopen. When guests arrived for their first Sunday jazz brunch, there were tears and hugs among the many customers who returned to the restaurant where they had celebrated their own family milestones over the years: weddings, anniversaries, birthdays.

“People walked in...and they started crying,” Brennan said. “And then we started crying. It was a real landmark, a real strong step back for the city of New Orleans.”

Ten years after Katrina, the thriving restaurant scene is not only a testimony to the nation’s love of Cajun and Creole cooking -- considered by many to be America’s truest indigenous cuisine. It also speaks volumes about the unwavering courage and determination of the Big Easy’s food community, and how selflessly they came together to save the culture they love.

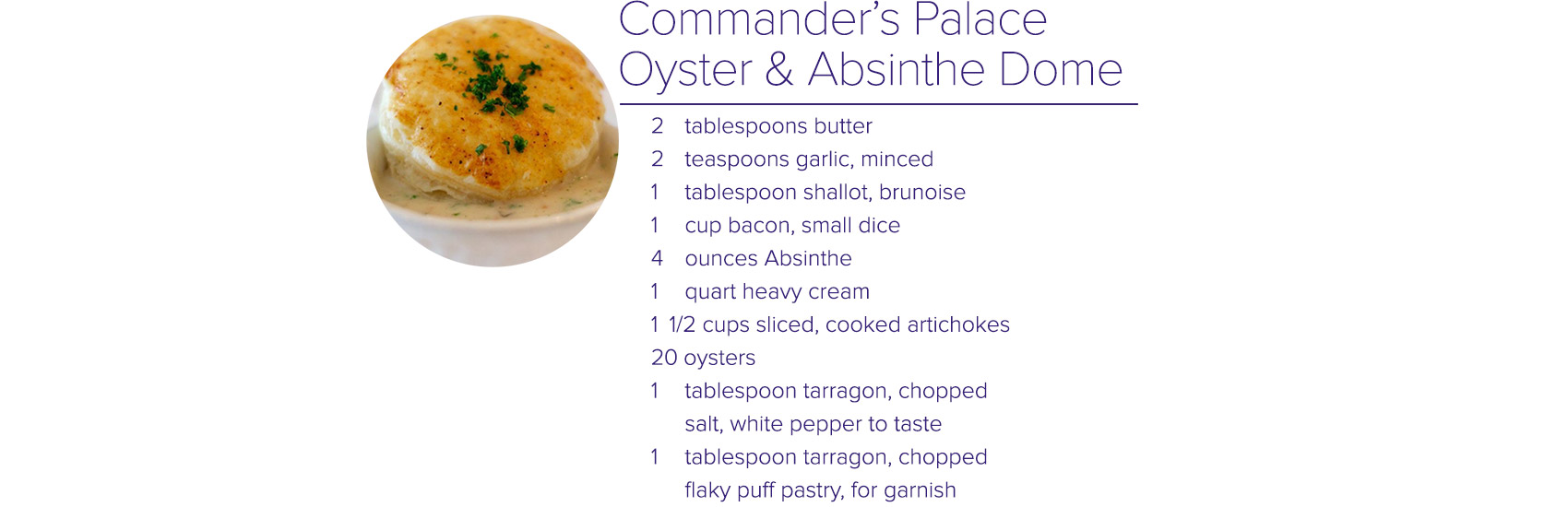

Yields 4 Portions

Place a medium sauce pan on the stove over medium high heat for 2 minutes to warm. Add the butter, garlic, shallots and bacon to the pot and stir for 2 to 3 minutes until garlic is slightly brown and bacon is rendered. Remove the sauce pot from the stove and deglaze with 3oz of absinthe. Return to the stove and flambé. When flames subside, reduce until the liquid is nearly evaporated and pour in the cream. Bring to a boil (be sure it doesn’t boil over). Reduce to the consistency of a thick soup. Add the artichokes and cook for 1 minute.

Add the oysters, tarragon, salt, pepper and final ounce of absinthe. Stir to incorporate. As the oysters cook, they will release their liquid, resulting in a thinner consistency. Finally, check the seasoning as oysters from different waters have different levels of natural salt. To serve, divide oysters evenly between 4 appetizer size ramekins. Pour in the sauce and cover each ramekin with a round of flaky puff pastry.

Recipe and photo courtesy of Commander’s Palace

Place a medium sauce pan on the stove over medium high heat for 2 minutes to warm. Add the butter, garlic, shallots and bacon to the pot and stir for 2 to 3 minutes until garlic is slightly brown and bacon is rendered. Remove the sauce pot from the stove and deglaze with 3oz of absinthe. Return to the stove and flambé. When flames subside, reduce until the liquid is nearly evaporated and pour in the cream. Bring to a boil (be sure it doesn’t boil over). Reduce to the consistency of a thick soup. Add the artichokes and cook for 1 minute.

Add the oysters, tarragon, salt, pepper and final ounce of absinthe. Stir to incorporate. As the oysters cook, they will release their liquid, resulting in a thinner consistency. Finally, check the seasoning as oysters from different waters have different levels of natural salt. To serve, divide oysters evenly between 4 appetizer size ramekins. Pour in the sauce and cover each ramekin with a round of flaky puff pastry.

Recipe and photo courtesy of Commander’s Palace

A VOICE OF RECOVERY IN THE FOOD COMMUNITY

Tom Fitzmorris is the beloved local radio show host of "The Food Show," the nation’s only three-hour food broadcast, which is devoted to New Orleans food.

When New Orleans was still in its infancy of recovery, he knew he had to find a way to get his radio show back on the air, to reassure the food-loving citizens of New Orleans that they all would find their way home again.

Fitzmorris at first thought that reporting about food might seem trivial in light of everyone’s loses. But he soon discovered how soothing it was for people to talk about food. He heard from listeners who wanted to know the status of their favorite restaurants. And he diligently reported nearly every triumph as recovery began to take hold, as one by one the lights turned back on in the city’s most iconic restaurants, sending residents a beacon of hope, and a signal to the world that New Orleans was coming back.

Not only did the restaurants help restore the economy, providing jobs and encouraging tourists to visit, they became the place where people found one another again. There were cheers and tears as familiar faces started to reappear, but most often there was what Fitzmorris refers to as the “Katrina hug,” when words were not enough to express the relief felt by friends and neighbors who had lost touch with each other in the chaos of evacuation.

Today, Fitzmorris says, “If the restaurant community had not come roaring back after the hurricane, the recovery would have been much slower and perhaps an ongoing disaster.”

He explains that the Gulf Coast cuisine has always been the great equalizer, and that is why it was also a source of strength.

“It's soul food and everyone eats it no matter what your background," Fitzmorris said. "Everyone eats gumbo, oysters on the half shell. With our food we told the world we are not dead yet. We can bring this back. It might seem frivolous to some, but we would see foie gras and soft shell crabs come back on the menu and people would be so ecstatic that they believed this city would come back. Because if the food came back everything could come back.”

MORE:

A Personal Essay by Robin Roberts

Katrina Survivor Describes Clinging to Trees for Hours as Husband Was Swept Away

How Cooking Helped Change the Life of a New Orleans Katrina Survivor

Design Director Lori Neuhardt | Produced by Lauren Effron, Eric Johnson and Danielle Genet