As federal law enforcement officials warn of a spike in “active shooter” incidents with schools as a prime target, a months-long investigation by ABC News has found that such plots are rooted more than ever in one of the nation’s worst school massacres, 15 years ago. At least 17 attacks and another 36 alleged plots or serious threats against schools since the assault on Columbine High School can be tied to that very massacre in 1999, when two seniors hunted down and killed 12 fellow students and a teacher before taking their own lives, ABC News determined.

Check out all 53 Columbine-linked cases

Ten cases tied to the April 20, 1999, massacre have emerged in the past year alone, more than any other year before it. And this school year has already seen one such plot uncovered.

For many of those caught up in Columbine, they begin to inhabit a world of fantasy, where they feel what many described as “a kind of kinship” with the Columbine shooters. And sometimes this fantasy turns into real action, with troubled youngsters seeking to outdo previous mass attacks.

In May – just six months ago – a Minnesota boy was arrested for allegedly planning to kill his family and then bomb his school on the anniversary of Columbine. In his interrogations with police, he allegedly explained why he wanted his attack to be in April, the “reasons” behind his attack, and how he wanted to do more damage than the Columbine shooters and the homegrown terrorists who bombed the Boston marathon in April 2013. At the time, his father told reporters he believes his son would not have actually carried out an attack. The 17-year-old currently faces charges of possessing explosive devices, after a judge threw out some of the most serious charges against him. Prosecutors are trying to get those charges reinstated.

Check out all 53 Columbine-linked cases

Ten cases tied to the April 20, 1999, massacre have emerged in the past year alone, more than any other year before it. And this school year has already seen one such plot uncovered.

For many of those caught up in Columbine, they begin to inhabit a world of fantasy, where they feel what many described as “a kind of kinship” with the Columbine shooters. And sometimes this fantasy turns into real action, with troubled youngsters seeking to outdo previous mass attacks.

In May – just six months ago – a Minnesota boy was arrested for allegedly planning to kill his family and then bomb his school on the anniversary of Columbine. In his interrogations with police, he allegedly explained why he wanted his attack to be in April, the “reasons” behind his attack, and how he wanted to do more damage than the Columbine shooters and the homegrown terrorists who bombed the Boston marathon in April 2013. At the time, his father told reporters he believes his son would not have actually carried out an attack. The 17-year-old currently faces charges of possessing explosive devices, after a judge threw out some of the most serious charges against him. Prosecutors are trying to get those charges reinstated.

The “Curse of Columbine” is a phenomenon underscored in documents, audio recordings and videos obtained by ABC News from police departments, prosecutors and courthouses across the country.

Most of the cases identified by ABC News involve young people struggling with mental illness or suffering from desperate feelings of anger and loneliness. Many of them come to believe “the only remedy” is to exert violent “domination” over targets and gain Columbine-like notoriety, according to FBI Assistant Director Jim Yacone.

In some cases, the connection to Columbine is hard to detect – it’s hidden in a bedroom closet, in a drawer, or simply in someone’s mind. For example, in August 2011, a 17-year-old was arrested for allegedly plotting an attack on Freedom High School in Tampa, Fla. He stockpiled potential bomb-making materials, dubbed himself “the Freedom High School shooter” and vowed to “beat” Columbine killers Eric Harris and Dylan Klebold. In his bedroom, police found a calendar with the words “The event!” written on April 20, 2012 – the anniversary of the Columbine shooting. He ultimately pleaded no contest to two weapons-related charges against him and was sentenced to 15 years in prison, after begging the judge for leniency. Before his sentencing, he expressed remorse and asked for an opportunity to “do right.” Though he “obviously was disturbed,” a defense expert determined at the time that nothing in the boy’s possession could have actually been turned into a working bomb, a lawyer who represented the boy told ABC News. Florida law “covers an attempt” to do something violent, and that’s what got him, the attorney said.

See what police found in Tampa kid’s room

Two years earlier, a 15-year-old student “filled with hate” walked into a Louisiana classroom with a .25-caliber handgun, opened fire and then killed himself. In his bedroom, police found a newspaper clipping with this headline: “10 years later, the real story behind Columbine.”

Most of the cases identified by ABC News involve young people struggling with mental illness or suffering from desperate feelings of anger and loneliness. Many of them come to believe “the only remedy” is to exert violent “domination” over targets and gain Columbine-like notoriety, according to FBI Assistant Director Jim Yacone.

In some cases, the connection to Columbine is hard to detect – it’s hidden in a bedroom closet, in a drawer, or simply in someone’s mind. For example, in August 2011, a 17-year-old was arrested for allegedly plotting an attack on Freedom High School in Tampa, Fla. He stockpiled potential bomb-making materials, dubbed himself “the Freedom High School shooter” and vowed to “beat” Columbine killers Eric Harris and Dylan Klebold. In his bedroom, police found a calendar with the words “The event!” written on April 20, 2012 – the anniversary of the Columbine shooting. He ultimately pleaded no contest to two weapons-related charges against him and was sentenced to 15 years in prison, after begging the judge for leniency. Before his sentencing, he expressed remorse and asked for an opportunity to “do right.” Though he “obviously was disturbed,” a defense expert determined at the time that nothing in the boy’s possession could have actually been turned into a working bomb, a lawyer who represented the boy told ABC News. Florida law “covers an attempt” to do something violent, and that’s what got him, the attorney said.

See what police found in Tampa kid’s room

Two years earlier, a 15-year-old student “filled with hate” walked into a Louisiana classroom with a .25-caliber handgun, opened fire and then killed himself. In his bedroom, police found a newspaper clipping with this headline: “10 years later, the real story behind Columbine.”

In April 2008, police arrested an 18-year-old man in South Carolina for allegedly plotting to bomb his school. In his bedroom, his parents and police found a journal praising “the actions of Harris and Klebold” and voice recordings threatening “Columbine III.” He ultimately pleaded guilty to federal charges in the case and was sentenced to 10 years in federal prison, where he is receiving psychiatric and psychological treatment. A lawyer who represented the 18-year-old said “it is important” to note that he was diagnosed as suffering from “major” and “untreated” mental health disorders, and that “mental illness played a defining role in the offense.” Since receiving treatment, he “was courteous, respectful, and modest” with “the ability to be a productive person, and I hope that in the future someone will give him a chance to demonstrate his good qualities, rather than discarding him as some Columbine copycat.”

So how do we stop or at least slow this dangerous phenomenon?

TREATMENT AND COUNSELING As described above, mental health treatment can be key. One Pennsylvania man who was arrested seven years ago for allegedly discussing a plot to attack his school told ABC News that court-ordered therapy pulled him from his “dark place” and “sense of hopelessness,” and he hopes “to make people understand that it's OK to talk about what you're going through, whether it's bullying, whether it's different issues of mental health.” Dillon Cossey, 21, said he never had any intention of actually doing anything violent, but acknowledged that for some people who “start to identify with violent individuals” like the Columbine shooters, “It could be a very dangerous mix.” In fact, one of the others arrested in a case identified by ABC News told police in 2012 that if he “went off the deep end … people would probably not be living.”

TREATMENT AND COUNSELING As described above, mental health treatment can be key. One Pennsylvania man who was arrested seven years ago for allegedly discussing a plot to attack his school told ABC News that court-ordered therapy pulled him from his “dark place” and “sense of hopelessness,” and he hopes “to make people understand that it's OK to talk about what you're going through, whether it's bullying, whether it's different issues of mental health.” Dillon Cossey, 21, said he never had any intention of actually doing anything violent, but acknowledged that for some people who “start to identify with violent individuals” like the Columbine shooters, “It could be a very dangerous mix.” In fact, one of the others arrested in a case identified by ABC News told police in 2012 that if he “went off the deep end … people would probably not be living.”

About three times a week, local and campus police across the country refer people in their communities to the FBI’s Behavioral Threat Assessment Center, which helps assess and “disrupt” someone who could pose a threat to others, according the FBI. Not one person referred to the FBI’s center has ever gone on to commit an act of mass violence, and sometimes the solution is as simple as guiding a potentially violent person to a nearby mentor or counselor, the FBI said.

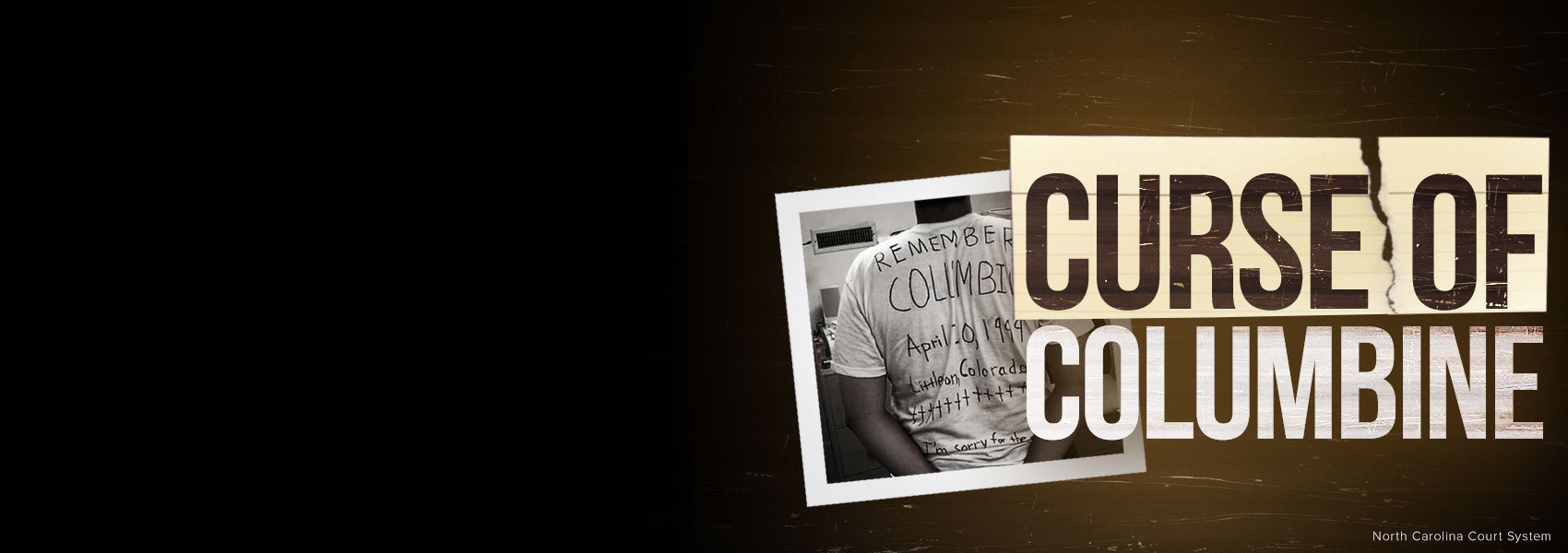

Perhaps no case illustrates the Columbine obsession and the role treatment can play in halting horror more than that of a North Carolina killer. In 2006, he killed his father and then opened fire at Orange High School, wearing a shirt that said, “Remember Columbine.” In videos and journals seized by police, he documented a tour he took to Colorado to see Columbine-related sites for himself, and talked about how he “can’t live like this anymore.”

Perhaps no case illustrates the Columbine obsession and the role treatment can play in halting horror more than that of a North Carolina killer. In 2006, he killed his father and then opened fire at Orange High School, wearing a shirt that said, “Remember Columbine.” In videos and journals seized by police, he documented a tour he took to Colorado to see Columbine-related sites for himself, and talked about how he “can’t live like this anymore.”

There’s also the case of a 16-year-old boy in Spring Branch, Texas, who allegedly plotted to detonate a bomb at his former high school. In his home, police allegedly found six carbon-dioxide canisters, instructions on how to turn them into an explosive device, and a hit-list with the phrase “Remember 4:20,” an apparent reference to the date of Columbine. He was reportedly charged with misdemeanor criminal intent, but due to the defendant’s age it’s unclear what happened next.

SPEAK UP Authorities encourage students and others to come forward to report any potentially worrisome behavior. In 2006, a boy in Green Bay, Wis., said he was “just saving my fellow students’ lives” when he notified authorities of an alleged plot to attack his high school. By contrast, five years earlier, a 14-year-old boy killed two fellow students at a high school outside San Diego, Calif., after telling a friend about his plans the night before. The friend never said anything to authorities because he thought the boy was kidding, as recounted to a local TV reporter at the time.

ADDRESS BULLYING Cossey said he believes schools “sweep bullying under the rug” and don’t do enough to stop it, which leads some bullied students to feel “no sense of justice” and hopeless.

DON’T NAME THEM?Law enforcement officials say it’s important to keep any offenders from gaining the notoriety they potentially crave. Law enforcement experts at Texas State University are pushing a “Don’t Name Them” campaign, encouraging media and others to refrain from naming anyone who commits a major attack. “We understand that an event happens, it has to be covered, [and] it has to be reported,” Pete Blair of Texas State told ABC News. “But there is no reason to make that person’s name a household name.” The FBI says it’s “very supportive of” the campaign.

DON’T NAME THEM?Law enforcement officials say it’s important to keep any offenders from gaining the notoriety they potentially crave. Law enforcement experts at Texas State University are pushing a “Don’t Name Them” campaign, encouraging media and others to refrain from naming anyone who commits a major attack. “We understand that an event happens, it has to be covered, [and] it has to be reported,” Pete Blair of Texas State told ABC News. “But there is no reason to make that person’s name a household name.” The FBI says it’s “very supportive of” the campaign.

THE RIGHT BALANCE While Columbine is impacting plots and threats even 15 years later, defense attorneys and others warn that law enforcement and school officials need to strike the right balance when branding someone a threat. Dariel Weaver, a public defender for the state of Colorado, told ABC News a recent case of his is a “terrifying example of what can happen when schools take a knee-jerk, reactionary response to perceived threats.”

Less than a year ago, a 15-year-old boy and a 16-year-old boy were arrested in Trinidad, Colo., for allegedly planning a shooting at their school after the winter break. Through interviews with the suspects and others who knew them, police learned that the 15-year-old had been bullied and idolized the Columbine shooters, according to police. But a search of the suspects’ homes did not turn up any weapons. It became “very clear very early on in the case that these two boys had absolutely no intention of doing anything at the school and were just “engaging in some ‘what-if’ hypothetical banter over lunch,” said Weaver, who represented one of the boys.

His client was ultimately found not guilty by a judge, and the case against the other boy was dismissed.

“Because the school and police department chose to arrest first and ask questions later, this young man was arrested, expelled, and frivolously charged with a felony; the administration and law enforcement bullied him far more severely than his peers did,” Weaver said.

Cossey echoed that sentiment, saying that when authorities and others “instantly jump to judging” kids who are interested in Columbine and violence, those people “sound just like the bullies at school.”

Less than a year ago, a 15-year-old boy and a 16-year-old boy were arrested in Trinidad, Colo., for allegedly planning a shooting at their school after the winter break. Through interviews with the suspects and others who knew them, police learned that the 15-year-old had been bullied and idolized the Columbine shooters, according to police. But a search of the suspects’ homes did not turn up any weapons. It became “very clear very early on in the case that these two boys had absolutely no intention of doing anything at the school and were just “engaging in some ‘what-if’ hypothetical banter over lunch,” said Weaver, who represented one of the boys.

His client was ultimately found not guilty by a judge, and the case against the other boy was dismissed.

“Because the school and police department chose to arrest first and ask questions later, this young man was arrested, expelled, and frivolously charged with a felony; the administration and law enforcement bullied him far more severely than his peers did,” Weaver said.

Cossey echoed that sentiment, saying that when authorities and others “instantly jump to judging” kids who are interested in Columbine and violence, those people “sound just like the bullies at school.”

By Pierre Thomas, Mike Levine, Jack Cloherty and Jack Date.

ABC News’ Megan Joyce, Leila Gharagozlou and Julia Noel contributed to this report

ABC News’ Megan Joyce, Leila Gharagozlou and Julia Noel contributed to this report