Tiny Bubbles: Favorite Drinks, Once Magnified, Become Art

Another Look at the New Year's Cocktail

New Year's Eve is a time for merriment and drinking. Nothing rings in the new year like a glass of bubbly but have you ever wondered what exactly is going into our bodies as we sing Auld Lang Syne? At FSU's chemistry department, in correlation with Bevshots, scientists have taken classic cocktails and magnified them up to 1000 times, producing some breathtaking images reminiscent of Kandinsky, and other abstract painters. All images can be purchased at the Bevshots website.

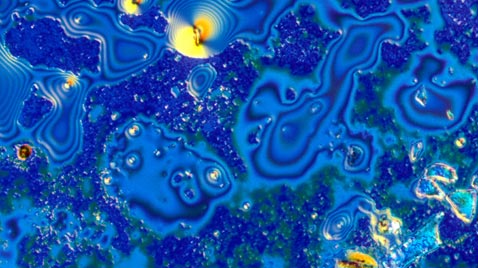

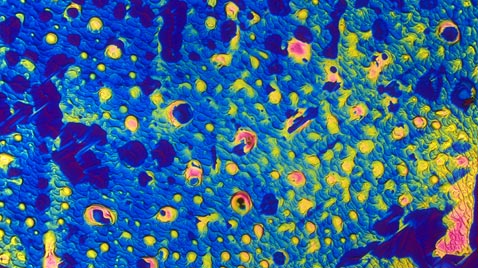

Just like snowflakes no two beverage crystals are exactly the same. An up-close-and-personal view of vodka is shown here.

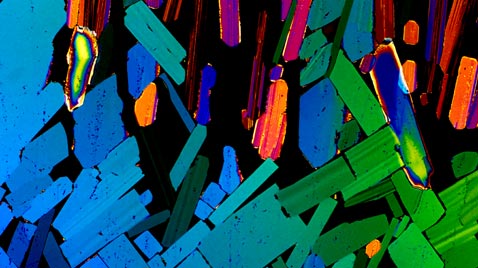

With a process developed at Florida State University, BevShots, based in Tallahassee, Fla., produces colorful images of wine, liquor and beer magnified up to 1,000 times. The company sells them to buyers as works of art. "Each image is a picture of beverage crystals taken through the lens of a polarized light microscope," said Lester Hutt, the company's president. Scotch is shown here.

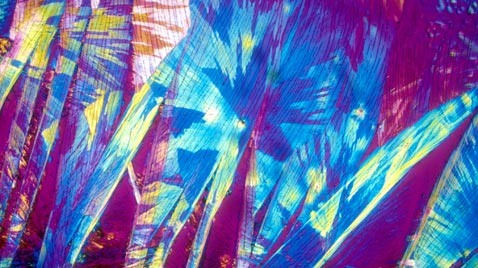

A microscopic picture of white wine is shown here. These colorful microscopic "shots" of alcoholic drinks reveal the incredible molecules that make up our favorite potent potables. They are sold as art works for buyers who appreciate the kaleidoscopic effects of the booze.

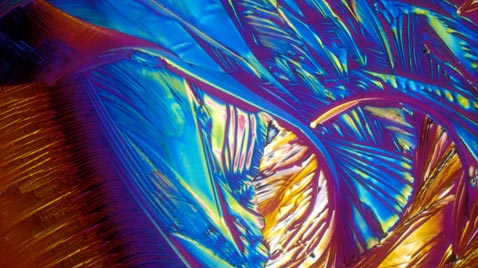

Next time you take a shot of tequila, remember that this is what it looks like when you zoom in.

Depending on the difficulty of crystallizing a beverage, the process can take anywhere from four weeks to more than six months. Red wine crystals are captured in this image.

A microscopic view of a glass of bubbly is shown here.

This is the only non-alcoholic beverage magnified- who knew each drop of a popular soft drink could look like this? A microscopic picture of Coca Cola taken in the chemistry department of Florida State University in Tallahassee, Fla.

To form the crystals, Lester Hutt said drops of a beverage are placed on a glass microscope slide to dry out. As the cocktail dries, the ingredients and impurities form crystals. To find crystals beautiful enough to use as art, Michael Davidson, the scientist who shot the images, often creates more than 200 slides of the same drink. A close-up image of American light beer is photographed here.

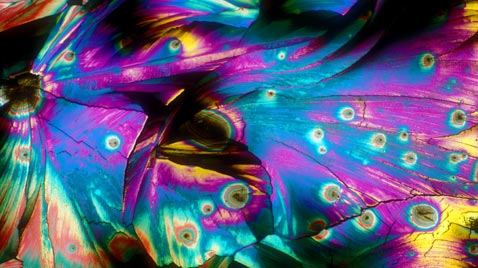

The variation in color and shape comes from the composition of the crystals, Hutt said. Some mixed cocktails, such as Pina Colada (shown here), contain a lot of sugar, which forms crystals differently than liquors like vodka with fewer impurities, he said.

The colors may look like they're manipulated by photo-editing software, but Hutt said they are real as real can be. As the polarized microscope light passes through the crystals, the light is refracted and creates a rainbow. The many colors of Mexican beer are show here.