The Radical Camera: New York's Photo League

In 1936, a group of young, idealistic photographers formed an organization in Manhattan called the Photo League. Artists in the Photo League were known for capturing sharply revealing, compelling moments from everyday life.

Coney Island ? circa 1947 (Sid Grossman/The Jewish Museum/© Howard Greenberg Gallery)

The cooperative's members included some of the most noted photographers of the mid-20 th century, including Berenice Abbott, Weegee, Lisette Model and Aaron Siskind, to name a few. The Photo League helped validate photography as fine art, presenting student work and guest exhibitions by established photographers like Eugène Atget, Henri Cartier-Bresson and Edward Weston among others.

"The Radical Camera," an exhibition at The Jewish Museum in New York, showcases Photo League images that are not only beautiful but harbor strong social commentary on issues of class, child labor and opportunity. The show explores the fascinating blend of aesthetics and social activism at the heart of the Photo League during its time.

Here is a sampling of images from the show, on view until March 25.

Precursors

"I have always been more interested in persons than in people." - Lewis Hine

Steamfitter ? 1920 : This portrait of a steamfitter at a powerhouse was one of hundreds Hine made of men and machines, a project that became a book called, "Men at Work." Elevating the worker to the status of an unsung "hero of industry," Hine suggests a harmony between the mechanic's physical prowess and the formidable machine. (Lewis Wickes Hine/Howard Greenberg Gallery)

Before the Photo League, a number of American photographers working in the early decades of the 20 th century were motivated by social and political concerns. Chief among them were Hine and Paul Strand. Hine, who trained as a sociologist, used photography as a tool for social reform. His empathetic pictures of workers were instrumental in changing labor laws in America.

The Great Depression

"The thing that shocks me and which I really try to change is the lukewarmness, the indifference, the kind of taking pictures that really doesn't matter." - Lisette Model

Lower East Side ? circa 1940 (Lisette Model/The Jewish Museum/© The Lisette Model Foundation, Inc.)

The economic turmoil of the 1930s wrought enormous social and political upheaval. In response, the government of President Franklin D. Roosevelt instituted massive relief programs known collectively as "the New Deal." The government funded unprecedented public arts projects, employing artists and making their work accessible to a broad public.

Small hand-held 35mm cameras introduced in the 1920s enabled a new kind of chance photography, at once casual and purposeful, and the Leaguers were inspired to make inequity and discrimination tangible in their work.

Zito's Bakery, 259 Bleecker Street ? 1937: The influence of the French documentary photographer Eugène Atget may be seen in this image of Zito's, the famous Italian bakery in Greenwich Village, one of many storefronts that Abbott photographed in the late 1930s. Sponsored by the Federal Art Project, a New Deal program, she produced over three hundred documents of New York's urban landscape. Her project culminated in the book Changing New York. (Berenice Abbott/The Jewish Museum)

Untitled (Brooklyn Bridge) ? 1938 (Alexander Alland/The Jewish Museum/© Estate of Alexander Alland, Sr.)

Untitled (Tenements, New York) ? circa 1937: Leftist political activism was a strong element in Consuelo Kanaga's work. Underlying this formal study of tenement laundry lines (a common motif in League imagery) is Kanaga's empathy for the living conditions of the working class. (Consuelo Kanaga/The Jewish Museum)

Salvation Army Lassie in Front of a Woolworth Store ? circa 1940 (Lee Sievan/The Jewish Museum/© Estate of Lee Sievan)

Max Is Rushing in the Bagels to a Restaurant on Second Avenue for the Morning Trade ? circa 1940 (Weegee/The Jewish Museum/© Weegee/International Center of Photography)

The Harlem Document (1936-1940)

The Harlem Document project's goal was to provide evidence of an impoverished community in peril and advocate for improvement of its living conditions. Ten photographers took part over a four-year period and exhibitions were held around New York.

Harlem Merchant, New York ? 1937 (Morris Engel/The Jewish Museum/© Estate of Morris Engel)

The Wishing Tree ? 1937 : Harlem's legendary Wishing Tree, bringer of good fortune, was once a tall elm that stood outside a theater at 132nd Street and Seventh Avenue. When it was cut down in 1934 Bill "Bojangles" Robinson, the celebrated tap dancer, moved the stump to a nearby block and planted a new Tree of Hope beside it to assume wish-granting duties. A piece of the original trunk is preserved in the Apollo Theater on 125th Street, where performers still touch it for luck before going onstage. (Aaron Siskind/The Jewish Museum/© Aaron Siskind Foundation/Courtesy Bruce Silverstein Gallery)

Playing Football, circa 1939 (Harold Corsini/George Eastman House, International Museum of Photography and Film/© Estate of Harold Corsini)

Untitled (Dancing School) ? 1938: Mary Bruce opened a dancing school in Harlem in 1937. For 50 years she taught ballet and tap, giving free lessons to those who could not afford them. Her illustrious pupils included Katherine Dunham, Nat King Cole, Ruby Dee, and Marlon Brando. (Sol Prom [Solomon Fabricant]/The Jewish Museum/© Estate of Sol Prom)

Though well-meaning, the project ultimately produced a stereotypical view of Harlem, with the African-American community portrayed in a negative light. Project leader Aaron Siskind later admitted: "Our study was definitely distorted. We didn't give a complete picture of Harlem. There were a lot of wonderful things going on in Harlem. And we never showed most of those."

The War Years

The early 1940s saw the country's rapid transition from New Deal recovery to war mobilization. The League rallied around war-related projects and half the membership enlisted in the armed services.

Walter Rosenblum served in the Army Signal Corps and later the Army Pictorial Service, becoming one of the most decorated World War II photographers. He landed in Normandy on D-Day morning and joined an anti-tank battalion that drove through France, Germany and Austria.

D-Day Rescue, Omaha Beach ? 1944 (Walter Rosenblum/Columbus Museum of Art/© Estate of Walter Rosenblum)

Shoemaker's Lunch ? 1944 (Bernard Cole/The Jewish Museum/© Estate of Bernard Cole)

The Red Scare

"I was natural for a Communist because I was Jewish. I looked like a Jew and lived in New York. I was always taken for a Communist." -Aaron Siskind

Lower East Side ? 1947: An advertisement for the film "Gentleman's Agreement" appears in this image of Rebecca Lepkoff's childhood neighborhood. The film addressed the persistence of anti-Semitism in America and won the Academy Award for Best Picture in 1947. Its political message was scrutinized by the House Un-American Activities Committee, and two of its Jewish actors were placed on the Hollywood Blacklist. (Rebecca Lepkoff/Columbus Museum of Art/© Rebecca Lepkoff)

Postwar prosperity replaced economic hardship and the threat of global fascism as the 1940s drew to a close. But in the midst of this new upward mobility, the League was forced to confront its progressive past. With the advent of the Cold War, leftist politics became suspect in America, and on Dec. 5, 1947, the U.S. attorney general blacklisted the Photo League as an organization considered "totalitarian, fascist, communist or subversive."

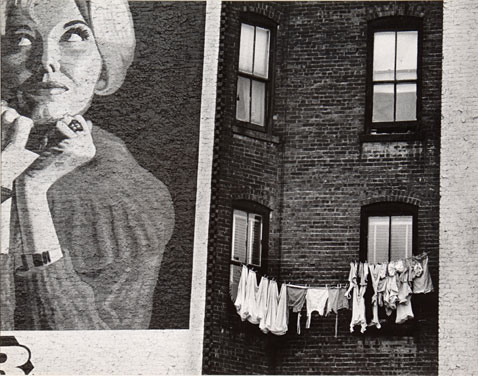

Lower Eastside Facade ? 1947: Erika Stone's adroit cropping of this image emphasizes the coy upward gaze of the woman in the advertisement, away from the laundry line (emblem of poverty), and suggests the social mobility of the postwar era. (Erika Stone/Columbus Museum of Art/© Erika Stone)

Butterfly Boy, New York ? 1949: This portrait of a young boy was taken near Knickerbocker Village, a public-housing complex on the Lower East Side that had replaced substandard tenements. Liebling's empathy and respect for his subject may be seen in the direct connection he establishes with the child, who stares stone-faced into the camera. (Jerome Liebling/The Jewish Museum/© Estate of Jerome Liebling)

Ideal Laundry ? 1946 (Arthur Leipzig/The Jewish Museum/© Arthur Leipzig)

Boy Jumping into Hudson River ? 1948 (Ruth Orkin/The Jewish Museum/© Estate of Ruth Orkin)

Game of Lynching, East Harlem ? 1947: In the late 1940s, Vivian Cherry documented violence in children's games-cops and robbers, cowboys and Indians, and these disturbing images of boys playing at lynching. The series was published by '48 Magazine of the Year; Photography republished them in 1952, commenting, "The pictures are not pretty, but they do represent an attempt to … use a camera as a tool for social research." (Vivian Cherry/The Jewish Museum/© Vivian Cherry)

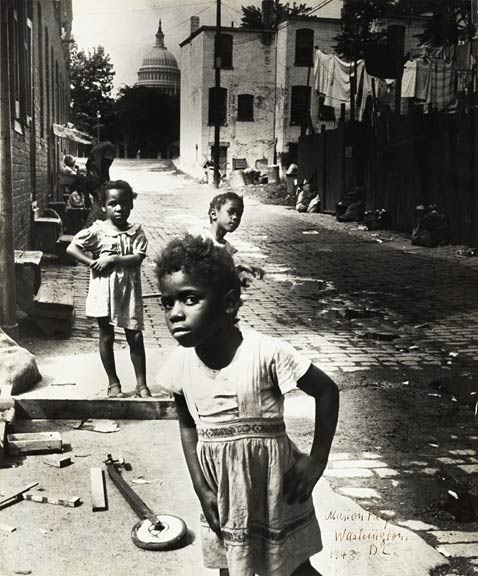

In the Shadow of the Capitol ? 1948 (Marion Palfi/The Jewish Museum/© 1998 Arizona Board of Regents)

Shout Freedom, Charlotte, North Carolina ? circa 1948: "Shout Freedom!" was a celebratory musical about the American Revolution. Rosalie Gwathmey captures the irony of the advertisement for black citizens in the Jim Crow South. She herself was familiar with civil-rights problems; her husband, the painter Robert Gwathmey, was subjected to surveillance and harassment by the FBI for his political activism. The blacklisting of the League in 1951 was the last straw: she destroyed many of her negatives and stopped making photographs. (Rosalie Gwathmey/The Jewish Museum/© Estate of Rosalie Gwathmey/Licensed by VAGA)

Sidewalk Clock, New York ? 1947: This unique sidewalk clock, embedded by Barthman Jewelers on the corner of Broadway and Maiden Lane in 1898, is a hidden gem of New York's former jewelry district. In 1946, it was estimated that 51,000 people unwittingly stepped on the clock between 11:00 a.m. and 2:00 p.m. each day. The clock, which was given a new face shortly after this picture was taken, still works today. (Ida Wyman/Columbus Museum of Art/© Ida Wyman)

A Center For American Photography

"I am a compassionate cynic … I have tried to let the truth be my prejudice." - W. Eugene Smith

Halloween, South Side ? 1951: This eerie image of children on Halloween hints at racial tensions at the dawn of the civil rights struggle. The effect is heightened by the tight cropping, the children's anxious expressions, and the close juxtaposition of masked and unmasked faces. (Marvin E. Newman/The Jewish Museum/© Marvin E. Newman)

Broken Window on South Street ? New York, 1948 (Rebecca Lepkoff/The Jewish Museum/© Rebecca Lepkoff)

In response to the blacklisting, the group mounted an exhibition entitled "This Is the Photo League," which showcased the diversity and quality of its members' work. While it achieved a measure of critical attention, the effort came too late and the political atmosphere was by then far too toxic. Membership and revenues diminished and the group was ostracized. By 1951, the Photo League could no longer sustain itself and was forced to close its doors as a casualty of the Cold War.

The League and its Legacy

Too rarely is the League credited for its early, pivotal role in redefining documentary photography, capturing sharply revealing moments from everyday struggles. The League had propelled documentary photography from factual images to more challenging ones - from bearing witness to questioning one's own bearings in the world.