Steelers Safety Sidelined by Sickle Cell Trait

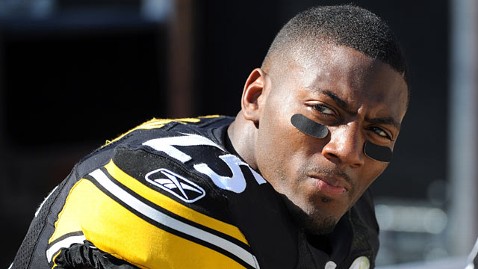

Steelers safety Ryan Clark will watch Sunday's game in Denver from the sidelines. (George Gojkovich/Getty Images)

Pittsburgh Steelers safety Ryan Clark will not play in Sunday's playoff game against the Denver Broncos because of a blood disorder bolstered by high-altitude, low-oxygen conditions.

Clark, 32, has sickle cell trait, which means he carries an abnormal version of the hemoglobin gene. Although he's spared the severe symptoms of sickle cell disease (in which both versions of the gene - one from each parent - are abnormal), Clark could suffer life-threatening organ damage playing in Denver's mile-high stadium.

"It was an easy decision for us," Steelers head coach Mike Tomlin said in a news conference Tuesday. "When looking at all of our data, we came to the determination he is at more risk so we are not going to play him. It's just that simple."

A 2007 game in Denver sent Clark into sickle cell crisis, a complication that cost him his spleen and gallbladder and ended his season.

"The hemoglobin actually crystallizes in the blood and the red blood cells become deformed," said Dr. Jasmine Zain, assistant professor of medicine at NYU Langone Medical Center.

Hemoglobin is the molecule in red blood cells that carries oxygen. "This causes the blood to sludge and block the blood vessels," she said.

Those blockages can cause organ failure, heart attack, stroke and excruciating joint pain, Zain added.

Since 2007, the Steelers have faced the Broncos in Denver twice, and Clark sat on the bench both times.

People with sickle cell trait usually live normal lives, often unaware of their condition.

"It's usually not a problem unless they're in a situation of hypoxia," Zain said, referring to the state of low oxygen levels in the body. "And for professional athletes, the oxygen requirements are higher. A normal person who has sickle cell trait and goes to Denver would probably not have an issue."

Clark will travel to Denver with his team and help out from the sidelines.

"It would have been an amazing triumph to come back and play there, to have things come full circle and to be all right," he told ESPN. "So to not be on the field is disheartening, but God has his plan."

Unlike people with sickle cell trait, who have some normal hemoglobin, people with full-blown sickle cell disease face life-threatening complications throughout their lives. "Their lives can be extremely difficult, even consumed by sickling," Zain said.

But thanks to treatments that lower the concentration of abnormal hemoglobin, as well as better management of complications, their life expectancies are growing. "Now we're seeing people in their 40s, 50s and 60s with sickle cell disease," she said. "They used to die in their 20s and 30s."

The only cure for sickle cell disease is a bone marrow transplant, usually from an unaffected sibling.