Early Brain Changes May Indicate Dyslexia

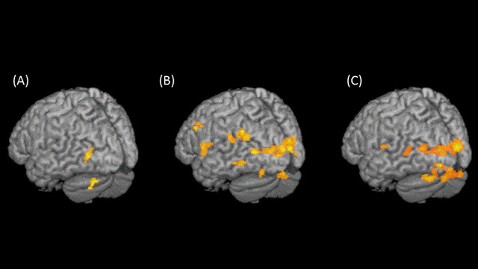

MRI images show brain activity of children with and without family history of dyslexia.

A group of researchers say they may be close to finding a way to resolve what's known as the "dyslexia paradox": the fact that the earlier a child is diagnosed with dyslexia, the easier it is to treat, but because the disorder is characterized by difficulty in reading and speaking, it is not typically diagnosed until a child reaches third grade, which many experts consider to be late.

The researchers at Children's Hospital Boston say they may now be able to detect dyslexia even before children pick up their first book, by studying MRIs to see how their brains are working.

Their study, published Monday in PNAS, took MRI brain images of 36 pre-reading level children, half of whom had a family history of dyslexia. The children, who were around age five, were asked to decide whether two similar sounding words start with the same sound.

Many children diagnosed with dyslexia exhibit insufficient brain activities in the rear left side of the brain, which is responsible for the development of language skills, according Nadine Gaab, associate professor of pediatrics at Children's Hospital in Boston and co-author of the study. Children with a family history of the condition are at higher risk to develop dyslexia.

The children were followed until they reached third grade, and those with a family history of the condition showed less brain activity in the back left side of the brain compared to those with no family history of dyslexia.

"The question is, are these children showing these brain changes as a result of dyslexia, or do these brain changes predate dyslexia?" said Gaab.

If these brain changes are observed before children are able to read, Gaab said there may come a time when clinician will be able to diagnose dyslexia before the children begin to show the first signs.

But the current study suggests we're not there yet. Although researchers found the brain changes in children with a family history of the dyslexia, the children studied have not been followed long enough yet to determine whether they are diagnosed with the condition.

Gaab said the next part of their study will determine if the children who exhibited less activity in the language area of the brain go on to receive a dyslexia diagnosis.