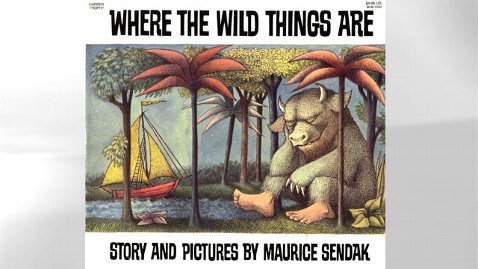

'Where the Wild Things Are:' The Psychology Behind Maurice Sendak's Classic

"I only have one subject. The question I am obsessed with is: How do children survive?" Maurice Sendak told Leonard Marcus, a children's book historian, in a 2002 interview. Sendak died today at age 83.

In just 10 sentences, Sendak's "Where the Wild Things Are," illuminated not only the protagonist Max's imagination, but also rage, a reaction to a mother's emotional absence and the overall darker, and neglected, parts of a child's psyche.

Clearly, Max, a young and unruly boy who is punished by his mother and sent to his room without dinner, depends on his mom. But his rage is apparent, and soon his room morphs into a strange forest. He takes a private boat to where the wild things are, and, despite their terrible roars and ghoulish features, manages to become their ruler through a magic trick. Max becomes the "most wild thing of all."

They play, but soon, Max commands them to stop and go to bed without supper, and he finds himself lonely as the king of the wild things, and wants to be where someone loves him "best of all." He returns to his room, where supper is waiting for him, and, with an added reassurance and charm that maybe only Sendak could pointedly portray, Max finds that the food is still hot.

In a 2009 article published in The Psychologist, Richard Gottlieb, a psychoanalyst based in Phoenix, analyzed the influences and motivations behind Sendak's illustrations and writing.

"Sendak's work in 'Where the Wild Things Are' is of particular interest to psychologists due to his strikingly unusual abilities to gain access to, and to represent in words and pictures, fantasies that accompany childish rage states," Gottlieb wrote in the paper.

"It is this capacity, I believe, that contributes to the appeal of his work to children who are unable or unwilling to articulate these states, and to adults who have forgotten them or do not wish to know about them," Gottlieb continued.

Sendak's other children's books, including "In the Night Kitchen" and "Outside Over There," focus on child rage and emotional unavailability of a mother. That rage then manifests in an altered state of consciousness, like a dream or fantasy, Gottlieb wrote. Ultimately, that fury and conflict is reconciled and signified through an otherwise innocuous even. In "Where the Wild Things Are," the reconciliation is represented through the warm food that Max finds from his mother has left for him.

And it likely could have been the author's own childhood from which he was pulling. Sendak was born in Brooklyn in 1928 to parents of Polish descent. In the interview, he told Marcus that his father's family was "destroyed" in the Holocaust.

"I grew up in a house that was in a constant state of mourning," he told Marcus. He also described his mother as disturbed, chronically sad and emotionally unavailable.

In the paper, Gottlieb noted that Sendak was surrounded by psychological proddings and teachings throughout his life, having undergone psychoanalysis for a period of his adult life. His partner, Eugene Glenn, with whom he lived for 50 years, was also a psychoanalyst.

It is disappointments, losses and destructive rage allow children to survive, Gottlieb wrote, and that is what Sendak captured so vividly in "Where the Wild Things Are." The power of art, imagination and daydream allow children to turn traumatic moments into vehicles for survival and growth.

Stanton Peele, a licensed psychologist and attorney who has authored several books on addiction, called Sendak's best-selling book, a "model for mindfulness," in an article for Psychology Today.

"'What an empowering, psychologically astute parable about a child learning that his anger, while sometimes overwhelming and scary, can be safely expressed and eventually conquered," Steele wrote in the article.

When Max leaves his imaginary land, Steele noted in the paper, "he - like the Wild Things - has made substantial progress in resolving his demons and rectifying his relationship with his Mom. And once again, great art has encapsulated a crucial psychological vision."

In a story that seems to ring true to Sendak's authentic perspective on childhood emotions, the author told NPR's Terry Gross in a 2011 interview that one particular correspondence with a young fan has always stuck out in his mind.

After responding to this child with a postcard and a drawing of a Wild Thing, he told Gross, "I wrote, 'Dear Jim, I loved your card.' Then I got a letter back from his mother and she said, 'Jim loved your card so much he ate it.' That to me was one of the highest compliments I've ever received. He didn't care that it was an original drawing or anything. He saw it, he loved it, he ate it."