Surgeons Still Make Preventable Mistakes

Image Courtesy The Turkewitz Law Firm

Reported by Dr. Lauren Browne:

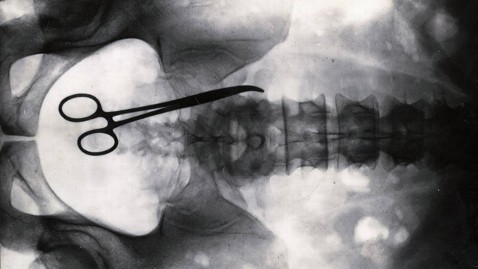

There are certain mistakes that should never happen to you during surgery. The surgeon should never accidentally leave a sponge in your body after he sews you up, perform surgery on the wrong part of your body, or perform the entirely wrong surgery on you.

These mistakes are known as "never events" because the medical community has agreed there is no legitimate reason for their ever happening. But new research finds that they still do occur at unacceptable rates, costing the healthcare system millions of dollars each year.

Using the National Practitioner Data Bank, an electronic warehouse of medical malpractice claims, researchers at John Hopkins University estimated the number of times that "never events" occurred within the past 20 years. They found that there were close to 10,000 reported instances when a foreign object was left in a patient, the wrong surgery was performed, or the surgery was performed on the wrong patient or wrong part of the body. These surgeries cost the healthcare industry an estimated $1.3 billion in malpractice payments over that same time period.

"It's a rare event but it's still an event that is entirely preventable," said Dr. Martin Makary, the lead investigator of the study published this week in the journal Surgery.

He and his team believe these figures underestimate the actual number of errors that occur, since prior studies have shown that most patients don't file medical claims when a mistake is made. Although the annual number of reported "never events" is on the decline, Makary and his team believe that even a single preventable error is one too many.

"There have been a lot of efforts over the past several years to make significant changes in patient care," said Dr. Sonali Desai, ambulatory medical director for patient safety at Brigham and Women's Hospital in Boston. She lists the creation of surgical safety checklists, improvements in communication and team training, and the development of better technology as key steps in ensuring that patients are safer.

"Surgeons are the captain of the ship, but it's a team effort," said Dr. Jeffrey Port, a cardiothoracic surgeon at New York Presbyterian-Weill Cornell who invented a product that uses radiofrequency technology to confirm that a patient's body is 100 percent sponge-free.

Mandatory safety procedures prior to the start of surgery were a nuisance at first, but over time proved valuable at ensuring patient safety, according to Port.

"I don't think we'll ever see zero [errors], but we can get very close," he said.

The study is not without its limitations, according to Dr. Desai, who points out that evaluating claims data through the National Practitioner Data Bank is only the tip of the iceberg. Hospital-based safety reporting systems keep track of not only medical malpractice claims, but also those medical errors that never make it into the legal system. This individualized hospital data may be more comprehensive, but it is also more difficult to aggregate and analyze on a national scale.

Makary acknowledges that the data sets are not perfect, and can only provide a rough estimate of the amount of preventable medical errors made every year, but the study serves to highlight the need for more accurate record keeping.

"Healthcare is operated by good people, but they're still human," he said. "The better able we are to remove errors from the system, the safer healthcare can be for everybody."

Check out your hospital's error rate at http://www.hospitalcompare.hhs.gov.