FDA Slaps 'Black Box' Warning on Malaria Drug Linked to Killings

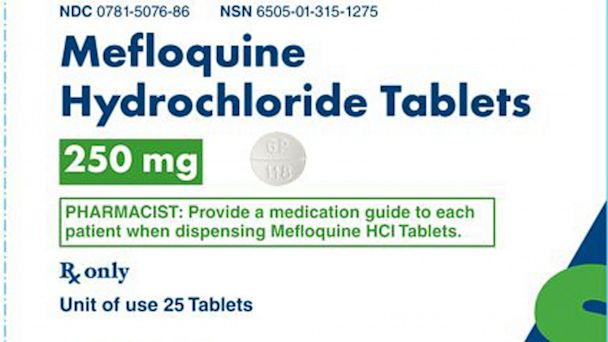

The FDA has strengthened the warning on the malaria drug, mefloquine hydrochloride. (Image credit: drugsee.com)

A common malaria drug that has been linked to the case of Staff Sgt. Robert Bales, who has pleaded guilty to killing 16 Afghan civilians last year, will carry a " black box" warning, the Food and Drug Administration said Monday.

The FDA says the drug, mefloquine hydrochloride, which was once marketed in the United States as Lariam, could cause serious neurological and psychiatric side effects that might become permanent. Such a warning on the revised patient Medication Guide dispensed with each prescription and wallet card is the most serious kind of warning about these potential problems, the FDA says.

Bales, who is facing a possible life sentence by a military court for the rampage in Afghanistan, might have used the antimalarial drug given routinely to soldiers in that part of the world. His lawyer, John Henry Browne, has said that he has documents indicating that Bales took mefloquine while in Iraq, but medical records in Afghanistan were incomplete.

Mefloquine was developed by the U.S. military and has been used for more than three decades by the government to prevent and to treat malaria among soldiers and Peace Corps workers.

Its temporary side effects are well-known: vivid dreams or hallucinations, ringing in the ears, depression and hallucinations. But the FDA now says symptoms like dizziness and loss of balance could become permanent. Psychiatric symptoms could continue for months or years.

The drug can cause varying neurological side effects 5 to 10 percent of the time, according to Dr. David Sullivan, an infectious disease specialist at the Johns Hopkins Malaria Research Institute in Baltimore.

The manufacturer also warns against prescribing it to anyone who has suffered a seizure or brain injury, according to the drug label.

An adverse-event report from the FDA recently emerged from March of 2012, written by an unidentified pharmacist, that cites a soldier-patient in the U.S. Army who "developed homicidal behavior and led to homicide killing 17 Afghanis."

Bales is not named in that anonymous report, which, if it refers to the same man, erroneously lists 17 dead, rather than 16.

A study of FDA adverse-event reports from 2004 to 2009 published in the journal PLOS One lists mefloquine as a drug that has been associated with violent behavior.

Mefloquine was first developed in the 1970s at the U.S. Department of Defense's Walter Reed Army Institute of Research as a synthetic analogue of quinine, the first effective treatment for malaria. It was licensed in 1989 by the FDA for use against chloroquine-resistant malaria.

The brand-name drug, Lariam, is manufactured by the Swiss company Hoffmann-La Roche.

The company has not manufactured the drug in the United States since 1998 when generic forms of mefloquine became available. But, according to Sullivan, Lariam is still available and "lingers on the market."

Company senior spokesman Chris Vancheri told ABCNews.com earlier this month that generic mefloquine "distributed by other companies continues to be approved by the FDA as safe and effective medicines."

Infectious disease expert Sullivan said mefloquine is largely safe and that he, too, takes a weekly dose of it when traveling and has "never had any side effects."

Sullivan said the military widely uses antimalarial drugs in Afghanistan, but mefloquine is not the first choice.

The military has several drugs in its arsenal for prophylactic (preventive) treatment of malaria, a mosquito-borne disease that causes fever, chills and flu-like illness that, if left untreated, can cause death. An estimated 219 million cases of malaria occurred worldwide and 660,000 people died in 2010, most in Africa, according to the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.