Trauma Surgeon Uses War Zone Skills to Better Treat Patients at Home

By ELY BROWN and LAUREN EFFRON

For trauma surgeon Dr. Peter Rhee, performing a couple of hernia repairs only to turn around hours later and treat a patient's life-threatening stab wounds is just another day in the office.

And he has seen much worse.

Rhee, the chief of trauma and emergency surgery at University of Arizona Medical Center (UAMC) in Tucson, spent most of his 25-plus year medical career in the U.S. Navy, honing his surgical skills on the battlefield while serving in Iraq and Afghanistan. There, he saw multiple casualty situations where the injuries were grim.

"In the military, the injuries are quite different than the civilian aspect and people die from these bombs blowing up, arms and legs off," Rhee said. "We were in Ramadi in Iraq … it was one of my first really bigger mass casualties. When the first six casualties came in were marines, six marines, 12 legs, and every one of those guys had a tourniquet on at the thigh."

Dr. Peter Rhee traveling through Iraq in battle gear in 2005. Credit: Courtesy Lukasz Swistun

When Rhee completed his training, he was one of seven trauma surgeons in the Navy. At the time of the 9/11 attacks, many military doctors had never seen a gunshot wound. Rhee, who was working at a trauma unit in Los Angeles, ran a special program to bring military doctors up to speed, exposing them to the types of injuries they would encounter in Afghanistan and later, Iraq.

"The people that we bring in from the reserves are people that haven't been doing trauma," Rhee told ABC News in 2003, as the country went to war in Iraq. "It's like taking a guy who's been flying a crop duster and expecting them to fly a jet airplane."

War has taught trauma surgeons to how to approach treating wounds that once might have been considered fatal. Former Congresswoman Gabby Giffords is living proof. As the head of the trauma center that cared for Giffords, Rhee oversaw her care after a lone gunman shot her in the head, as well as the care of others who were seriously wounded that day.

"The survival rate from being shot in the brain was only 10 percent but now at least in our institution we're up to about 46 percent," Rhee said. "That's because our surgeons and our neurosurgeons have worked together to be very aggressive on who we operate on … The war that we had in Iraq showed us that when we operate more often on these people shot in the brain the survival rate is higher."

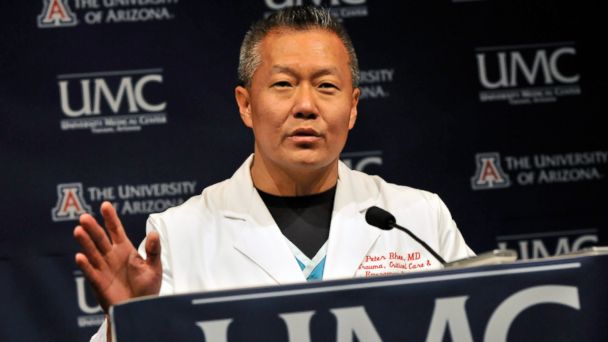

Dr. Peter Rhee speaks about the improved condition Gabby Giffords in this Jan 12, 2011, file photo in Tucson, Arizona.

Rhee wrote about Giffords' case and others in a new memoir, "Trauma Red: The Making of a Surgeon in War and in America's Cities," red being the code word in his trauma center to signify that a patient's life is in immediate danger.

"Nightline" spent time with Rhee during a 24-hour shift at UAMC, as he deals with multiple patients with life-threatening injuries and shows how practicing medicine in a war zone has made him a better doctor on this battlefield at home.

Dr. Peter Rhee during a shift at University of Arizona Medical Center (UAMC) in Tucson, Arizona. Credit: Ziemba Photographic