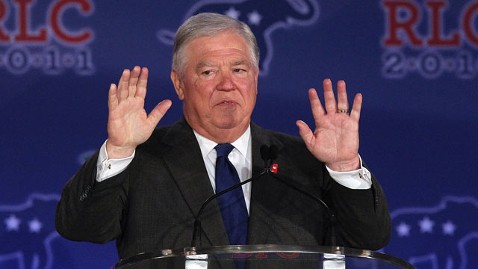

Pardon Me: Is Southern Custom Behind Haley Barbour's Clemencies?

Justin Sullivan/Getty Images

Former Mississippi Gov. Haley Barbour's decision to grant clemency to some 208 convicted felons right before he left office has focused the national spotlight on a unique practice that's relegated to a handful of states: inmates working in governor's mansion.

Four prisoners pardoned by Barbour last Friday worked at the mansion he resided in for eight years. All are convicted murderers.

Mississippi is one of the few states where the "trusty" system is still thriving. Under that system, well-behaved prisoners are allowed to clean, work in the kitchen, wait tables and wash cars at the governor's mansion, no matter what their crime was.

Proponents say the system helps cut state costs and allows prisoners to put their time to use. North Carolina has a similar program that uses inmates for upkeep of a part of the governor's residence. South Carolina did the same, but ended its program in 2001 after inmates were found to be having sex in the governor's residence.

Barbour told The Associated Press in 2008 that it was customary for Mississippi governors to cut short the sentences of inmates who served at the mansion, a tradition that dates back generations. At the time, he faced similar backlash for releasing trusty Michael David Graham, who served 19 years of his life sentence for killing his ex-wife. Graham walked free after working eight years in the governor's mansion.

The tradition of having inmates work at the governor's resident is unique to the South, observers say, and is partially inspired by the states' religious history. Even nationally, the pardoning system, from the state to the federal level, is rooted in some ways in the Judeo-Christian tradition, said P.S. Ruckman, Jr., a professor of political science at Rock Valley College in Illinois, who is writing a book on pardons.

"In the federal system, wardens would recommend Christmas pardons to the president. They don't do that anymore," he said. But "one out of every two pardons granted by the president in the last 39 years has been granted in the month of December."

Founding father Alexander Hamilton saw pardons as a critical part of the system of checks and balances, and until modern times U.S. presidents handed them out liberally.

"The founding fathers thought the pardon power was an important part of our system of checks and balances. It's a formal recognition of what we all know - that courts are not perfect, prosecutors are not, juries are not, legislators are not. So the pardon power is the executive check on those other two branches of government," Ruckamn said.

But it was more than just a political ideology. It was also grounded in the idea of forgiveness and in giving second chances.

"This is the only unfettered power bestowed on the executive by the founding fathers," said Dafna Linzer, a senior reporter at ProPublica who has written extensively about pardons. "That's because they believed in overriding injustice and in second chances."

The practice, however, has diminished over time as the legal and corrections systems have evolved.

Though politically, conservatives tend to be stricter on such pardons, Southern states stand out when it comes to their record and diligence in granting pardons or commutations, which involves cutting a prisoner's sentence.

States such as Georgia, Alabama, South Carolina and Arkansas "have a regular routine practice of pardoning that works very well and serves both the people and the government pretty well," said Margaret Love, a clemency attorney and former U.S. pardons attorney under President Bill Clinton's administration.

The first three have independently appointed pardon boards that issue clemencies after thorough reviews, instead of the governor.

As for Arkansas, Ruckman cites Democratic Gov. Mike Beebe as "one of the nation's most steady dispensers of gubernatorial clemency."

Even among Republican presidential candidates, Texas Gov. Rick Perry's record of clemency is more generous than his chief rival Mitt Romney, who proudly boasts of never having pardoned one inmate.

But experts say that the phenomenon is not limited to the South and that it's hard to distinguish regional differences.

Nationally and at the federal level, the number of clemencies granted have dropped in recent years. Because it can also have long-term national consequences, many governors across the country who have national ambitions often err on the side of caution when pardoning offenders. Former Arkansas Gov. Mike Huckabee took much heat for commuting a man who was later charged with killing four police officers. The Republican governor issued 1,000 commutations and pardons in office, more than what was granted by three of his predecessors combined. Former Minnesota Gov. Tim Pawlenty also pardoned a sex offender who was later charged with child abuse.

"It is safe to say that pardons are not being given out very generously in any state," Ruckman said. States like Arkansas "are kind of a standout."