Romney Challenged on How Much Class Size Matters

Image credit: Mary Altaffer/AP Photo

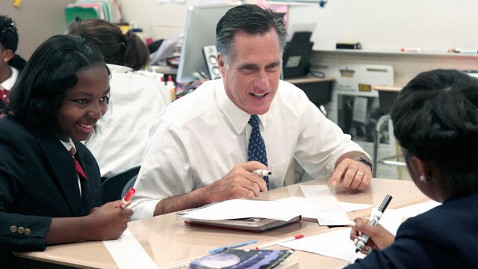

Teachers in Philadelphia were quick to take on Mitt Romney Thursday when he said that small class size was not key to students' success. They quickly told the candidate about their own struggles to teach effectively in packed classrooms.

"I heard your position on class size and testing," said Steven Morris, a teacher at the West Philadelphia Universal Bluford Charter School, which serves students from kindergarten through sixth grade. "But you know, I can't think of any teacher in the whole time I have been teaching, 13 years, who would say that more students [in the classroom] would benefit."

Morris was one of 11 teachers and educational leaders who joined Romney for a roundtable discussion meant to highlight Romney's newly unveiled education platform .

"And I can't think of a parent that would say I would like my teacher to be in a room with a lot of kids and only one teacher," Morris continued. "So I'm wondering where this research comes from."

Kenneth Gamble, the founder of the charter school later turned the discussion back to Romney, asking him bluntly, "What's your view on it?"

Romney cited a study by the McKinsey Global Institute that he said "proved" that having fewer students in a classroom didn't make as much of a difference as most people believe.

"Schools that are the highest performing in the world - their classroom sizes are about the same as in the United States," Romney said. "So it's not the classroom size that is driving the success of those school systems."

What's responsible for the success, Romney said, are involved parents and good teachers and administrators.

A teacher countered with his own study, a University of Tennessee analysis of class size that he said concluded that smaller classes were the most beneficial in the first through third grades, but less so after that.

"If you have small classes in those primary years, those most important years, that's what makes the difference," the teacher said. "You go to school from first to third grade; you learn to read. From third grade on, you read to learn. So if you don't get that reading piece, you never catch up. … And then once you do that, once you have kids kind of stabilized and everybody is on the same page, you can have … bigger classes."

There have been a host of studies about class size. That University of Tennessee study the teacher mentioned has been widely written about in education circles. Frederick Mosteller, a Harvard professor of statistics, analyzed it and wrote that "it was clear that smaller classes did produce substantial improvement in early learning and … and that the effect of small class size on the achievement of minority children was initially about double that observed for majority children, but in later years, it was about the same."

The McKinsey study that Romney cited also said as much: "The available evidence suggests that, except at the very early grades, class size reduction does not have much impact on student outcomes. … More importantly, every single one of the studies showed that … variations in teacher quality completely dominate any effect of reduced class size."

Parents generally believe that smaller classes benefit their children because they believe they'll get more attention from teachers. But in Florida in 2002, an amendment was passed to cut down on class size, and education analysts noted that schools had to hire unqualified teachers to lead the extra classes, which in some cases weren't even held in proper classrooms.

Costs are a factor too, especially in an environment of austere budgets. The Brookings Institute estimated that adding one student to the national student-teacher ratio would save $12 billion each year in teacher salary costs. That would also result in 7 percent of teachers losing their jobs.

"The primary difficulty in interpreting this research is that schools with different class sizes likely differ in many other, difficult-to-observe ways," the Brookings analysis noted.

Romney didn't only rely on the study he cited. In describing his education policy, he said that when he was governor of Massachusetts, he gathered data from across the state and found that smaller classroom size did not correlate with better student performance.

"I came into office and talked to people and said what do we do to improve our schools, and a number of folks said we need smaller classroom sizes, that will make the biggest difference," said Romney. "We had 351 cities and towns, and I said let's compare the average class size from each district with the performance of our students. Let's test our kids and see if there is a relationship. And there was not.

"As a matter of fact, the district with the smallest classrooms, Cambridge, had students performing in the bottom 10 percent," said Romney. "So just getting smaller classrooms didn't seem to be the key."

Today was certainly not the first time Romney has stood by his claim that class size isn't key when it comes to students' success. During a debate last September in Orlando, Fla., he suggested that the argument for smaller class size was born from the teachers' unions.

"All the talk about we need smaller classroom size … that's promoted by the teachers unions to hire more teachers," he said.