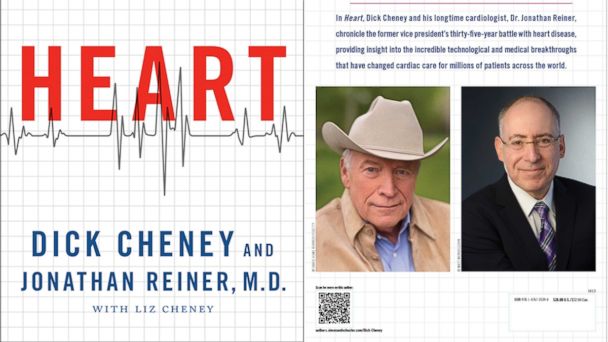

Read an Excerpt of Dick Cheney's New Book 'Heart: An American Medical Odyssey'

Scribner

Prologue

Vice President Cheney

June 2010

If this is dying, I remember thinking, it's not all that bad. It had been thirty-two years since my first heart attack. I'd had four additional heart attacks since then and faced numerous other health challenges. Now, in the summer of 2010, seventeen months after I left the White House, I was in end-stage heart failure.

On a trip to Jackson Hole, Wyoming, in May, it had become clear my weakened heart could not tolerate the high altitude. I returned to Washington on an emergency flight, and as the plane took off, I realized I might never see my beloved Wyoming again. Since then, my wife, Lynne, and I had been at our house in McLean, Virginia. When I got up in the morning, all I wanted to do was sit down in my big easy chair, watch television, and sleep.

What was happening to me was hardly a surprise. I had lived with coronary artery disease for many years, and I had long assumed it would be the cause of my death. Sooner or later, time and medical technology would run out on me. Now my heart was no longer providing an adequate supply of blood to my other vital organs. My kidneys were starting to fail. I believed I was approaching the end of my days, but that didn't frighten me. I was pain free and at peace, and I had led a remarkable life.

I thought about final arrangements. I wanted to be cremated and have my ashes returned to Wyoming. It was a difficult subject to broach with my family. They weren't eager to discuss it. For them, talking about it made an already difficult situation even worse. But I needed them to know. And I needed to say good-bye. As my condition deteriorated that summer, my cardiologist, Dr. Jonathan Reiner, had raised the possibility of having a left ventricular assist device (LVAD) implanted in my chest, and I agreed to be briefed on it at Inova Fairfax

Hospital in Northern Virginia, which has one of the most active LVAD programs in the country.

The LVAD transplant team showed me the device, which connects to the left ventricle, the main pumping chamber of the heart. The LVAD passes blood through a small pump operating at nine thousand revolutions per minute and returns it to the aorta, the largest artery in the human body, ensuring an adequate blood supply to the vital organs. The device is powered by a driveline that passes through the wall of the chest to an external set of batteries or an electrical outlet.

The idea of being kept alive by a battery-driven piece of equipment operating at high speed inside my chest was a bit daunting at first, but it soon became apparent that this option offered real hope and the possibility of extending my life long enough to be eligible for a new heart. Previously we had never really considered a heart transplant as an option for me because I clearly wouldn't live long enough to work my way up the transplant list to become eligible for a heart. The average wait was about twelve months. The medical team explained that although the LVAD was originally designed as a bridge to a transplant, some patients were deciding to live with the device.

I was impressed with the individuals on the LVAD/transplant team: they clearly knew their business. It was also apparent that they respected and welcomed Jon Reiner, who although he practices at George Washington University Hospital, would be included as an integral part of the team. That carried great weight with me given all that Jon and I had been through together over the past fifteen years.

The preceding weeks had been challenging. I not only had many of the symptoms of a failing heart, I was also, due to the anticoagulants I was taking, suffering severe nosebleeds, including one so massive it required emergency surgery and a number of blood transfusions. On more than one occasion that spring, we had found ourselves speeding down the George Washington Parkway in Northern Virginia toward my doctors and the emergency room at George Washington University Hospital in the District of Columbia. In addition, my heart failure was causing severe sleep apnea. As soon as I nodded off to sleep, I would find myself awake again, gasping for air.

On July 4, I'd experienced internal bleeding in my thigh and was rushed to George Washington University Hospital as fireworks lit up the night sky. At the hospital, they gave me narcotic painkillers, which, as we were on the way home and stuck in holiday traffic, caused me to be sick to my stomach. The list of things I could not do grew. I'd stopped climbing the stairs. I could no longer walk to the end of the driveway to pick up the morning newspapers. I barely had the strength to walk the length of the hallway between our bedroom and my office. My world shrank until I was barely able to leave my bed. By the time I was admitted to Inova Fairfax Hospital on July 6, 2010, it was clear that there really was no choice: without the LVAD surgery I would not survive.

My last memory of that evening is of Jon Reiner and the other doctors and my family gathered around my bed in the intensive care unit. The doctors explained that although they had originally scheduled the surgery for July 8, my situation was worsening and they recommended taking me immediately to the operating room. After I listened to the doctors, I asked Lynne and our daughters, Liz and Mary, what they thought. One by one, they each agreed that we should not delay. "Okay," I said, "let's do it."

Like "This Week" on Facebook here . You can also follow the show on Twitter here .

Go here to find out when "This Week" airs in your area.