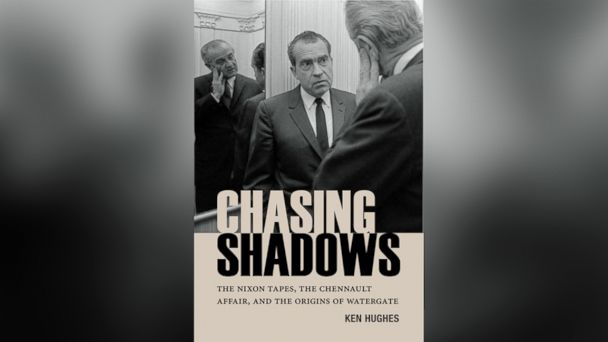

Book Excerpt: 'Chasing Shadows' by Ken Hughes

University of Virginia Press

INTRODUCTION

What more could we possibly need to know about Watergate? Four decades have passed since Richard Nixon left the White House looking like a man whose worst fears were being realized. But he had not yet hit bottom. President Gerald Ford's blanket pardon soon relieved him of the fear of prosecution and imprisonment, but that was not the ultimate threat Nixon faced. His presidency had been ended by a handful of tapes, secretly recorded on his own orders via microphones hidden in the Oval Office and other locations where he conducted the people's business. Public exposure of the full collection of Nixon tapes could destroy much of what remained of his reputation. The 3,432 hours of recordings captured a pivotal time in his presidency and American history. During the time of his secret taping, February 16, 1971, to July 12, 1973, Nixon negotiated the diplomatic opening to China, the first nuclear arms limitation treaty with the Soviet Union, and a settlement of what was then America's longest war, while winning a landslide reelection that realigned American politics and (not coincidentally) committing the wide-ranging abuses of power known collectively as Watergate. Until his dying day, the former president waged a legal battle to keep the public from learning what was on the rest of his tapes. The reasons became clear after his death, as the federal government gradually released most of the Nixon tapes (while withholding material on policy, privacy, and national security grounds) over the next two decades, a process completed only in August of 2013. At the same, the National Archives made public many of the 50 million pages of Nixon administration documents in its collection.

In an article reflecting on the fortieth anniversary of the Watergate break-in, Carl Bernstein and Bob Woodward, the two investigative journalists whose trailblazing articles in the days and months following the burglary started to expose the pervasive abuses of power behind it, marveled at the wealth of documentation now available: "Today, much more than when we first covered this story as young Washington Post reporters, an abundant record provides unambiguous answers and evidence about Watergate and its meaning." From this record, Woodward and Bernstein concluded that Watergate consisted of five wars waged by Nixon: "against the anti-Vietnam War movement, the news media, the Democrats, the justice system and, finally, against history itself."

The Chennault Affair played an unacknowledged, largely unseen, role in all five of these Watergate wars, driving some of Nixon's most outrageous assaults on war critics, journalism, the opposition, justice and history. The affair is a thread running through the Huston Plan, the Enemies List, and the Special Investigations Unit ("the Plumbers"), and it provides clearer answers to questions about some of the more outlandish decisions Nixon made. Why was his reaction to the leak of the Pentagon Papers so extreme? Why was he obsessed with getting his hands on all government documents related to his predecessor's decision to stop bombing North Vietnam in 1968? Why did he order the Watergate cover-up?

The Chennault Affair is not, however, the magical key to all of Watergate; it's part of a much bigger, complicated story. Many factors contributed to Nixon's fall, far more than I can fit in these pages. Wand-waving accounts that reduce the complexity of Nixon's downfall to a single cause are the preserve of Watergate revisionists. From time to time a new theory emerges placing the blame for Nixon's downfall on the scheming of a scapegoat (or, more marketably, a shadowy conspiracy of scapegoats). John W. Dean plays a recurring, featured role in these fantasies. Ever since Dean went from White House counsel to witness for the prosecution in the spring of 1973, Nixon and his defenders have tried to shift responsibility for Watergate onto his shoulders. Dean was a key figure in the cover-up, but not the central one. That was Nixon. The notion that the president was the victim of a criminal conspiracy rather than the perpetrator of one cannot survive the tape-recorded sound of him calling the shots from the Oval Office.

"His secret tapes-and what they reveal-will probably be his most lasting legacy," Woodward and Bernstein wrote in 2012. The authors of two enduring classics on Watergate, All the President's Men and The Final Days, found that there was even more to the story than investigators uncovered at the time: "The Watergate that we wrote about in the Washington Post from 1972 to 1974 is not Watergate as we know it today. It was only a glimpse into something far worse."

Since 2000 I have studied the White House tapes as part of the Presidential Recordings Program founded by the University of Virginia's Miller Center. These years of research have convinced me that the origins of Watergate extend deeper than we previous knew to encompass a crime committed to elect Nixon president in the first place. Chasing Shadows tells the story of that crime and its role in the unmaking of the president.

Watch the trailer for the book here:

Reprinted from Chasing Shadows: The Nixon Tapes, the Chennault Affair, and the Origins of Watergate by Ken Hughes by permission of the University of Virginia Press. For more: http://www.upress.virginia.edu or http://www.chasing-shadows.com

Like "This Week" on Facebook here . You can also follow the show on Twitter here .

Go here to find out when "This Week" is on in your area.