Like Pompeii, Ancient China Forest Buried by Volcano

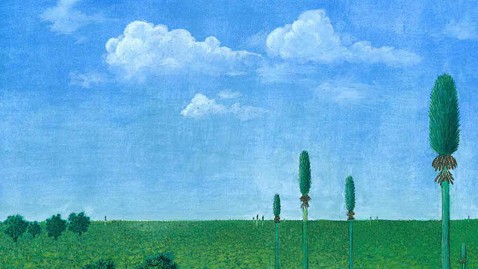

Artist's conception of Permian forest as it might have appeared before volcanic eruption. Credit: Ren Yugao

Long ago and far away, 298 million years ago in what is now called Inner Mongolia, a volcano erupted and sent ash in all directions. It would have been just one more forgotten prehistoric catastrophe, coming as it did in the Permian period before the dinosaurs, except that it buried a tropical forest nearby, much as Mt. Vesuvius would bury the Roman city of Pompeii eons later.

Now, Chinese scientists have found that ancient forest - destroyed by the ash but also preserved by it, giving them a chance to look at life there as it would have been in its very last days. The plants are fossils now, but Jun Wang of the Nanjing Institute of Geology and Palaeontology and his team were able to place them exactly, and reconstruct a swath of about 10,000 square feet. They have reported their find in Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences.

What was the world like back then? The climate was not much different, in general, than it is now, though probably a bit warmer and drier. Today's continents were far in the future; they still formed a single giant land mass scientists have called Pangaea. The forest, as described by Wang and his colleagues, would have been dominated by ferns and some taller trees, with a layer of peat on the ground, and a few inches of standing water. If there were animals, such as insects or primitive amphibians, the researchers did not find them.

"This ash-fall buried and killed the plants, broke off twigs and leaves, toppled trees, and preserved the forest remains in place within the ash layer," write the scientists. "The layer is now 66-cm thick [about 40 inches] after compaction and lithification."

The reference to Pompeii is not accidental; the scientists use it in the title of their paper. The real Pompeii was buried in A.D. 79 - a mere blink of an eye ago compared to the Mongolian forest - but the same thing happened. A place destroyed was frozen in time, giving us insights into long-ago life just before a calamity.

"It's marvelously preserved," said Hermann Pfefferkorn, a paleobiologist at the University of Pennsylvania who joined in the forest study, in a statement from Penn. "We can stand there and find a branch with the leaves attached, and then we find the next branch and the next branch and the next branch. And then we find the stump from the same tree."

"It's like Pompeii," he said. "It's a time capsule and therefore it allows us now to interpret what happened before or after much better."