Mona Lisa Sent to the Moon

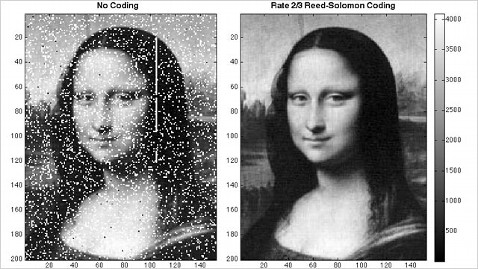

Left: The Mona Lisa, transmitted to the moon and back. Right: the picture with software corrections. Credit: Xiaoli Sun/Goddard Space Flight Center/NASA

NASA researchers can now boast they sent one of most famous faces in history into the cosmos. It's 240,000 miles each way; they did it with a laser.

Engineers at the Goddard Space Flight Center in Maryland successfully beamed an image of the Mona Lisa from the earth to NASA's Lunar Reconnaissance Orbiter, a spacecraft that has been orbiting the moon since 2009. They said it was the first demonstration of laser communication with a ship in deep space.

A black and white version of Leonardo's painting was transmitted, pixel by pixel, to the Lunar Orbiter Laser Altimeter (LOLA) on the spacecraft. The image was sent using the same laser pulses sent to track LOLA's position.

"This is the first time anyone has achieved one-way laser communication at planetary distances," said LOLA's principal investigator, David Smith of the Massachusetts Institute of Technology, in a statement. "In the near future, this type of simple laser communication might serve as a backup for the radio communication that satellites use. In the more distant future, it may allow communication at higher data rates than present radio links can provide."

While lasers are used to track the orbit of the spacecraft precisely enough to determine variations in the moon's gravity, this successful transmission suggests the possibility of being able to "send data to a spacecraft at a low data rate," Xiaoli Sun, a LOLA scientist at NASA Goddard, told ABCNews.com.

"In the future, we will use lasers instead of microwaves to communicate in deep space - to do it better, faster, and with smaller equipment," Sun said.

Sun said over a four-month period, scientists sent random numbers via laser to the lunar orbiter. Then they tried some simple images, and finally, Leonardo's famous painting. Sun said it took the team about ten tries to get it right; turbulence in Earth's atmosphere interfered with the signals.

"We have paved the way for a future lunar laser communication demonstration that is going to be launched later this year," Sun said. "We provided proof that you can do it, and you can do it to the moon."

So why the Mona Lisa?

"At the end, we just like to pick something that's more real so it can give us a feeling about what information was sent, and what was lost due to turbulence," Sun said. "One of the guys on our team suggested it because it was a familiar image with lots of subtleties, so we can see instantly how much information was sent."