Joy Johnson knew the drill.

The 2013 New York City marathon would be the 25th consecutive time that she ran the iconic race, and just like how she had routines for her daily jogs, there was an order to the way she went about running the marathon every November.

She and a friend – most times, it was her sister, Faith – traveled to New York from her adopted home state of California.

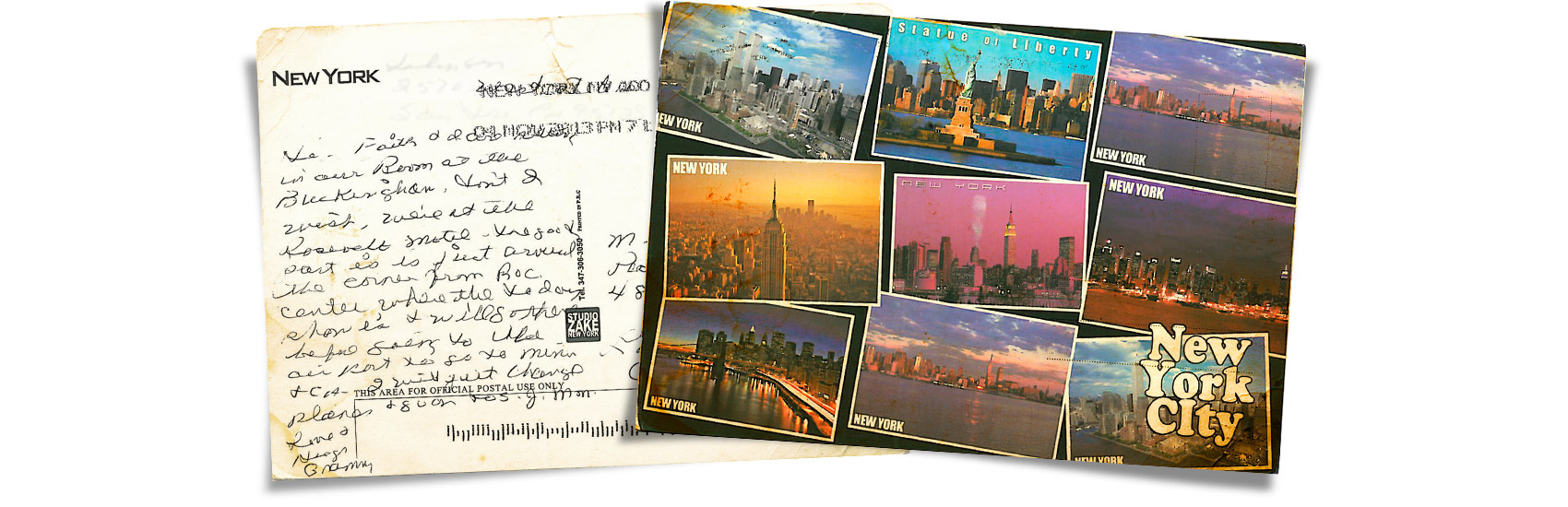

She’d pick up her bib the day before, maybe visit an art museum and send her granddaughter a postcard.

The day of the race, she’d pick out a colorful bow to pin to her silver hair to make sure she would stand out among the masses. Faith would cheer her on from various spots that flanked the course as it weaved through the five boroughs.

At some point later in the day, the pair would meet up at the hotel after Joy, 86, had a chance to sit in the bathtub for a while and ease her joints.

The difference between the 2013 race and the 24 others that preceded it in New York, and the dozens of others that she’d run around the country, came when she tripped and fell at the 20-mile mark.

Aides along the route urged her to go to the hospital but she waved them off. She finished the race - with a bloody cut on her right forehead - in just under eight hours. Even with the fall, she was only 13 minutes slower than her previous time.

She told Faith and her daughter, Diana Boydston, that everything was fine.

And, as usual, she went to take a nap.

But this time, she never woke up.

“That was how she wanted to pass away because she knew that when it was her time,” her daughter, Diana Boydston said.

“It was her time.”

Aides along the route urged her to go to the hospital but she waved them off. She finished the race - with a bloody cut on her right forehead - in just under eight hours. Even with the fall, she was only 13 minutes slower than her previous time.

She told Faith and her daughter, Diana Boydston, that everything was fine.

And, as usual, she went to take a nap.

But this time, she never woke up.

“That was how she wanted to pass away because she knew that when it was her time,” her daughter, Diana Boydston said.

“It was her time.”

Running hadn’t always been a passion of Joy’s. She was always fit, sure. Joy made her career as a physical education teacher and high school volleyball and track and field coach in San Jose, California.

But it wasn’t until she retired in her 50s that she started running.

Really, it came at the urging of a friend, her daughter said. The pair first ended up running around the neighborhood, then smaller 5k and 10k races - and then eventually doing their first New York City marathon together in 1988.

Joy’s husband, Newell, was a supporter of his wife's new hobby, and while he didn't join her (Boydston, one of Newell’s four children from a previous relationship, joked that she gets “couch potato genes from him,") he stood out front of their home with a stopwatch in hand when she thought that she needed to speed up a bit.

But it wasn’t until she retired in her 50s that she started running.

Really, it came at the urging of a friend, her daughter said. The pair first ended up running around the neighborhood, then smaller 5k and 10k races - and then eventually doing their first New York City marathon together in 1988.

Joy’s husband, Newell, was a supporter of his wife's new hobby, and while he didn't join her (Boydston, one of Newell’s four children from a previous relationship, joked that she gets “couch potato genes from him,") he stood out front of their home with a stopwatch in hand when she thought that she needed to speed up a bit.

That said, she was more interested in the social aspects of the sport than the speed. Once she got to the track, sometime after 5:00 a.m., it was as if she was the mayor. She was the leader of the so-called track pack, her next door neighbor and fellow runner Tom Sutton said. She would walk and talk with others, often picking up trash teens had left at the track from a football game or soccer match the night before.

"I would tell her that she could get cut from the broken bottles and not to do it," Sutton told ABC. "She ignored me and told me the track was our responsibility. Soon we were all doing it."

The “track pack” would arrive at slightly different points as the sun rose, and Sutton would get to the track at around 5:45 a.m. As soon as he did, Joy would leave the pack, "“run up behind me and put her arm in my arm and call me 'Sir Thomas,'" he said.

After a quick chat-- updates on their respective schedules for the coming day or details about how her granddaughter's choir concert-- Joy would rush back to the other members of the pack and start her training.

Joy’s friends and relatives don’t remember her accolades on the track so much as her Scandinavian Jelly Drop cookies (her granddaughter Leah’s favorite), or the Persimmon bread that she would bake for Sutton when he helped her with particularly taxing yard work after Newell died.

“I would ask her for the recipes and she said ‘Oh, it’s in my brain!’ She would not give out those recipes,” Sutton said.

The recipes came out whenever she baked with Leah, who grew up in the same house as Joy and is now is a junior at Cal State-Long Beach. Or when she had her annual Christmas party for the ‘track pack,’ complete with a wood fire, cookies and fudge served promptly at 6 a.m. so that everyone could still get their workouts in.

For those she left behind, there are constant reminders of Joy.

"I would tell her that she could get cut from the broken bottles and not to do it," Sutton told ABC. "She ignored me and told me the track was our responsibility. Soon we were all doing it."

The “track pack” would arrive at slightly different points as the sun rose, and Sutton would get to the track at around 5:45 a.m. As soon as he did, Joy would leave the pack, "“run up behind me and put her arm in my arm and call me 'Sir Thomas,'" he said.

After a quick chat-- updates on their respective schedules for the coming day or details about how her granddaughter's choir concert-- Joy would rush back to the other members of the pack and start her training.

Joy’s friends and relatives don’t remember her accolades on the track so much as her Scandinavian Jelly Drop cookies (her granddaughter Leah’s favorite), or the Persimmon bread that she would bake for Sutton when he helped her with particularly taxing yard work after Newell died.

“I would ask her for the recipes and she said ‘Oh, it’s in my brain!’ She would not give out those recipes,” Sutton said.

The recipes came out whenever she baked with Leah, who grew up in the same house as Joy and is now is a junior at Cal State-Long Beach. Or when she had her annual Christmas party for the ‘track pack,’ complete with a wood fire, cookies and fudge served promptly at 6 a.m. so that everyone could still get their workouts in.

For those she left behind, there are constant reminders of Joy.

For Dick Beardsley, the head of a marathon training camp that Joy regularly attended in her home state of Minnesota, he remembers her on particularly grueling sets of hill runs.

“All of our other campers would smile with relief when they reached the top of the hill,” he told ABC News. “Joy was the only one that smiled all the way to the top.”

For Boydston, it’s whenever she has a craving for vanilla ice cream, which was Joy’s favorite. Or whenever she passes Joy’s room just down the hall from her own bedroom.

For Sutton, it’s when he has to go get his own newspaper in the mornings, which was a chore that Joy took upon herself to take on for a handful of neighbors.

"I used to take it for granted, you know, 'Why is she doing this? I could just walk a little ways and get my own paper,'” Sutton told ABC News. "But her -- She was gone on vacation or out of town, I would miss it. I'd have to put my shoes on and walk outside!"

And for Leah, it’s the post card she got from her “Grammy Joy” on her final trip to New York. She didn’t receive the postcard until several days after Joy’s death, but when it arrived at her freshman dorm, she noticed it had been postmarked on the day that Joy died: Nov. 4, 2013.

"It felt like a movie when I got it. I started crying," Leah said.

"The whole thing was just, wow," Boydston said, now nearly two years later.

Published on October 28, 2015

Additional Credits

Executive Producer DAN SILVER

Managing Editor XANA O'NEILL

Creative Design Director LORI NEUHARDT

“All of our other campers would smile with relief when they reached the top of the hill,” he told ABC News. “Joy was the only one that smiled all the way to the top.”

For Boydston, it’s whenever she has a craving for vanilla ice cream, which was Joy’s favorite. Or whenever she passes Joy’s room just down the hall from her own bedroom.

For Sutton, it’s when he has to go get his own newspaper in the mornings, which was a chore that Joy took upon herself to take on for a handful of neighbors.

"I used to take it for granted, you know, 'Why is she doing this? I could just walk a little ways and get my own paper,'” Sutton told ABC News. "But her -- She was gone on vacation or out of town, I would miss it. I'd have to put my shoes on and walk outside!"

And for Leah, it’s the post card she got from her “Grammy Joy” on her final trip to New York. She didn’t receive the postcard until several days after Joy’s death, but when it arrived at her freshman dorm, she noticed it had been postmarked on the day that Joy died: Nov. 4, 2013.

"It felt like a movie when I got it. I started crying," Leah said.

"The whole thing was just, wow," Boydston said, now nearly two years later.

Published on October 28, 2015

Additional Credits

Executive Producer DAN SILVER

Managing Editor XANA O'NEILL

Creative Design Director LORI NEUHARDT